Copyright 2016 by Lesley M. M. Blume

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Blume, Lesley M. M., author.

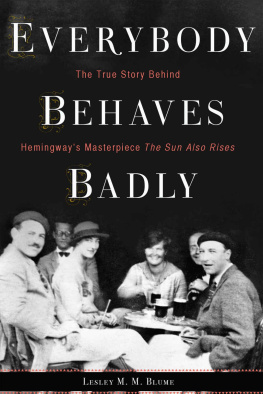

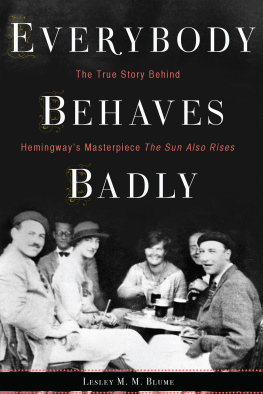

Title: Everybody behaves badly : the true story behind Hemingways masterpiece The Sun Also Rises / Lesley Blume.

Description: Boston : Eamon Dolan/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015037016 | ISBN 9780544276000 (hardback) | ISBN 9780544237179 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Hemingway, Ernest, 18991961. Sun also rises. | Hemingway, Ernest, 18991961Homes and hauntsSpain. | Hemingway, Ernest, 18991961Homes and hauntsFranceParis. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Artists, Architects, Photographers. | LITERARY CRITICISM / American / General.

Classification: LCC PS3515.E37 S9216 2016 | DDC 813/.52dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015037016

Cover design by Nicole Caputo

Cover photograph by unknown photographer, courtesy of The Ernest Hemingway Photo Collection / John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

Text permission credits appear on .

Photo credits appear on .

v1.0516

For G. R. M.

Authors Note

The letters and other documents quoted in this book appear exactly as they were written, including the writers original spelling and grammar.

Introduction

I N MARCH 1934, Vanity Fair ran a mischievous editorial: a page of Ernest Hemingway paper dolls, featuring cutouts of various famous Hemingway personas. On display: Hemingway as a toreador, clinging to a severed bulls head; Hemingway as a brooding, caf-dwelling writer (four wine bottles adorn his table, and a waiter is seen toting three more in his direction); Hemingway as a bloodied war veteran. Ernest Hemingway, Americas own literary cave man, declared the caption. Hard-drinking, hard-fighting, hard-lovingall for arts sake.

Throughout his life, additional personas would attach themselves to him: rugged deep-sea fisherman; big-game hunter; postwar liberator of the Paris Ritz; white-bearded Papa. He relished all of these identities and so did the press. When it came to selling copy, Hemingway was one of Americas most versatile leading men, and certainly one of the countrys most fascinating entertainers.

By then, everyone had long forgotten one of his earliest roles: unpublished nobody. It was one of the few Hemingway personas that never really suited him. In fact, in the early 1920sstrapped for cash, ravenous for recognitionhe was frantic to rid himself of it. Even in the earliest days of his career, his ambition seemed limitless. Unfortunately for him, the literary gatekeepers proved uncooperative at first. Hemingway was ready to dominate the world of letters, but its citizens were not yet willing to succumb. Mainstream publications turned down his short stories; his rejected manuscripts came back to him and were shoveled through the mail slot in his apartments front door.

The rejection slip is very hard to take on an empty stomach, Hemingway later told a friend. There were times when Id sit at that old wooden table and read one of those cold slips that had been attached to a story I had loved and worked on very hard and believed in, and I couldnt help crying.

During such moments of despair, it is unlikely that Hemingway realized that he was actually one of the luckier writers in modern history. Circumstances often seemed to conspire in his favor. All of the right things made their way to him at the right moment: motivated mentors, publisher patrons, wealthy wivesand a trove of material just when he needed it most, in the form of some delectably bad behavior among his peers, which he promptly translated into his groundbreaking debut novel, The Sun Also Rises, published in 1926. In the books pages, those co-opted anticsbenders, hangovers, affairs, betrayalstook on a new and loftier guise of their own: experimental literature. Thus elevated, all of this bad behavior rocked the literary world and came to define Hemingways entire generation.

Everyone knows how this story ends: to say that Hemingway eventually became famous and successful is a gross understatement. A Nobel laureate, he has been widely called the father of modern literature and for decades has been read in dozens of languages around the globe. More than half a century after his death, he still commands headlines and crops up in gossip columns.

What follows is the story of how Hemingway became Hemingway in the first placeand the book that set it all in motion. The backstory of The Sun Also Rises and that of its authors rise are one and the same. Critics have long cited Hemingways second novel, A Farewell to Arms, as the one that established him as a giant in the literary pantheon, but in many ways, the significance of The Sun Also Rises is much greater. As far as literature was concerned, it essentially introduced its mainstream readers to the twentieth century.

The Sun Also Rises did more than break the ice, says Lorin Stein, editor of the Paris Review. It was modern literature fully arrived for a grand public. Im not sure that there was ever another moment when one novelist was so obviously the leader of a whole generation. You read one sentence and it doesnt sound like anything that came before.

Not that there werent other tremors before this earthquake. A small movement of writers had been trying to shove literature out of musty Edwardian corridors and into the fresh air of the modern world. It was a question of who would break through firstand who could make new ways of writing appealing to the mainstream reader, who, for the most part, still seemed to be perfectly satisfied with the more florid, verbose approaches of Henry James and Edith Wharton. James Joyces radical novel Ulysses, for example, had blown the minds of many postwar writers.

But at first the work was hardly a mainstream sensation: it wasnt even released in book form in the United States until the 1930s. Paris-based experimentalist Gertrude Stein had resorted to self-publishing her works, which were often deemed incomprehensible by those who actually did read them. One of her books reportedly sold a mere seventy-three copies in its first eighteen months of existence. F. Scott Fitzgerald had also been striving to reinvent the American novel and felt that he had succeeded with the publication of The Great Gatsby in 1925. Yet while the content of his novels was thoroughly modernflappers, bootleggers, and other exotic urban creatureshis style remained decidedly old-school.

Fitzgerald was a nineteenth-century soul, says Charles Scribner III, a former director at Charles Scribners Sons, which published both Fitzgerald and Hemingway for the majority of their careers. [He] was wrapping up a grand tradition; he was the last of the romantics. He was Strauss.

Hemingway, by contrast, was Stravinsky.

He was inventing a whole new idiom and tonality, explains Scribner. And he was completely twentieth century. As one prominent critic noted around that time, Hemingway succeeded in doing for writing what Picasso and the cubists had been doing for painting: after the debut of the primitive modern idiom of cubism and Hemingways stark, staccato prose, nothing would ever be the same again. Modernity had found its popular creative leaders.