Parts of this book first appeared in New Yorker magazine 1997, 2013 Splendide Mendax, Inc.; and in National Geographic and at the National Geographic website 2015, 2016 Splendide Mendax, Inc.

Copyright 2017 by Splendide Mendax, Inc.

Photo credits can be found .

Jacket design by Flag. Typographic styling by Jim Cozza. Photography by Herman Estevez.

Cover copyright 2017 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Grand Central Publishing

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

grandcentralpublishing.com

twitter.com/grandcentralpub

First edition: January 2017

Grand Central Publishing is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Grand Central Publishing name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging.in.Publication Data

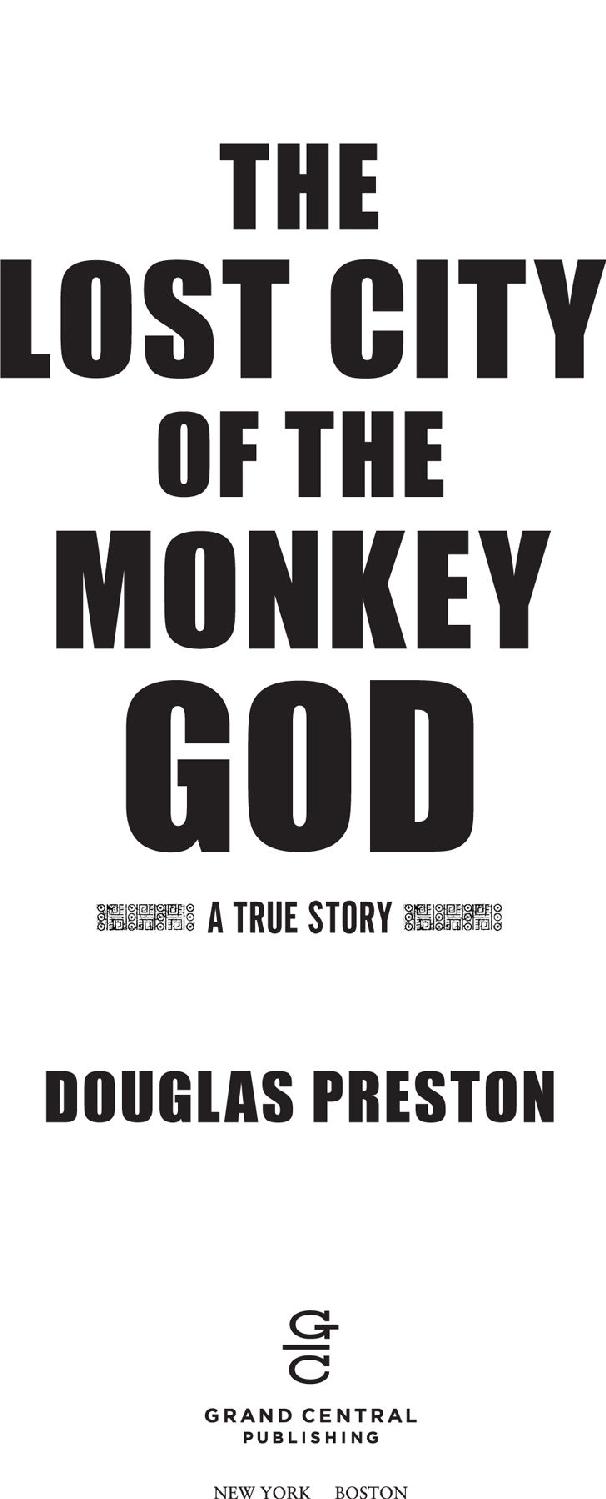

Names: Preston, Douglas J., author.

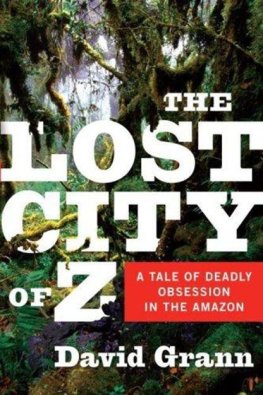

Title: The Lost City of the Monkey God / Douglas Preston.

Description: First edition. | New York : Grand Central Publishing, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016037247| ISBN 9781455540006 (hardback) | ISBN 9781455540020 (e-book)| ISBN 9781455569410 (large print) | ISBN 9781478964520 (audio CD) | ISBN 9781478964513 (audio download)

Subjects: LCSH: Mosquitia (Nicaragua and Honduras)Description and travel. | Mosquitia (Nicaragua and Honduras)Discovery and exploration. | Extinct citiesMosquitia (Nicaragua and Honduras) | Cities and towns, AncientMosquitia (Nicaragua and Honduras) | Indians of Central AmericaMosquitia (Nicaragua and Honduras)Antiquities. | Mosquitia (Nicaragua and Honduras)Antiquities. | Preston, Douglas J.TravelMosquitia (Nicaragua and Honduras) | BISAC: HISTORY / Americas (North, Central, South, West Indies). | HISTORY / Expeditions & Discoveries. | HISTORY / Latin America / Central America.

Classification: LCC F1509.M9 P74 2017 | DDC 972.85dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016037247

ISBNs: 978-1-4555-4000-6 (hardcover), 978-1-4555-4002-0 (ebook), 978-1-4555-6941-0 (large print)

E3-20161123-JV-PC

Contents

Navigation

To my mother Dorothy McCann Preston Who taught me to explore

D eep in Honduras, in a region called La Mosquitia, lie some of the last unexplored places on earth. Mosquitia is a vast, lawless area covering about thirty-two thousand square miles, a land of rainforests, swamps, lagoons, rivers, and mountains. Early maps labeled it the Portal del Infierno, or Gates of Hell, because it was so forbidding. The area is one of the most dangerous in the world, for centuries frustrating efforts to penetrate and explore it. Even now, in the twenty-first century, hundreds of square miles of the Mosquitia rainforest remain scientifically uninvestigated.

In the heart of Mosquitia, the thickest jungle in the world carpets relentless mountain chains, some a mile high, cut by steep ravines, with lofty waterfalls and roaring torrents. Deluged with over ten feet of rain a year, the terrain is regularly swept by flash floods and landslides. It has pools of quickmud that can swallow a person alive. The understory is infested with deadly snakes, jaguars, and thickets of catclaw vines with hooked thorns that tear at flesh and clothing. In Mosquitia an experienced group of explorers, well equipped with machetes and saws, can expect to journey two to three miles in a brutal ten-hour day.

The dangers of exploring Mosquitia go beyond the natural deterrents. Honduras has one of the highest murder rates in the world. Eighty percent of the cocaine from South America destined for the United States is shipped through Honduras, most of it via Mosquitia. Drug cartels rule much of the surrounding countryside and towns. The State Department currently forbids US government personnel from traveling into Mosquitia and the surrounding state of Gracias a Dios due to credible threat information against U.S. citizens.

This fearful isolation has wrought a curious result: For centuries, Mosquitia has been home to one of the worlds most persistent and tantalizing legends. Somewhere in this impassable wilderness, it is said, lies a lost city built of white stone. It is called Ciudad Blanca, the White City, also referred to as the Lost City of the Monkey God. Some have claimed the city is Maya, while others have said an unknown and now vanished people built it thousands of years ago.

On February 15, 2015, I was in a conference room in the Hotel Papa Beto in Catacamas, Honduras, taking part in a briefing. In the following days, our team was scheduled to helicopter into an unexplored valley, known only as Target One, deep in the interior mountains of Mosquitia. The helicopter would drop us off on the banks of an unnamed river, and we would be left on our own to hack out a primitive camp in the rainforest. This would become our base as we explored what we believed to be the ruins of an unknown city. We would be the first researchers to enter that part of Mosquitia. None of us had any idea what we would actually see on the ground, shrouded in dense jungle, in a pristine wilderness that had not seen human beings in living memory.

Night had fallen over Catacamas. The expeditions logistics chief, standing at the head of the briefing room, was an ex-soldier named Andrew Wood, who went by the name of Woody. Formerly a sergeant major in the British SAS and a soldier in the Coldstream Guards, Woody was an expert in jungle warfare and survival. He opened the briefing by telling us his job was simple: to keep us alive. He had called this session to make sure we were aware of the various threats we might encounter in exploring the valley. He wanted all of useven the expeditions nominal leadersto understand and agree that his ex-SAS team was in charge for the days we would be in the wilderness: This was going to be a quasi-military command structure, and we would follow their orders without cavil.

It was the first time our expedition had come together in one room, a rather motley crew of scientists, photographers, film producers, and archaeologists, plus me, a writer. We all had widely varying experience in wilderness skills.

Woody went over security, speaking in his clipped, British style. We had to be careful even before we entered the jungle. Catacamas was a dangerous city, controlled by a violent drug cartel; no one was to leave the hotel without an armed military escort. We were to keep our mouths shut about what we were doing here. We were not to engage in conversation about the project within hearing of hotel staff, or leave papers lying around our rooms referring to the work, or conduct cell phone calls in public. There was a large safe available in the hotels storage room for papers, money, maps, computers, and passports.

The valley, Woody continued, appeared to be an ideal habitat for the fer-de-lance.