www.hodder.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 1970 by Hodder and Stoughton

An Hachette UK company

This edition published in 2016

Copyright 1970, 1995 Times Newspapers Ltd

The right of Nicholas Tomalin and Ron Hall to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 473 63537 1

Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

www.hodder.co.uk

Contents

The young apostle had died striving for his idea by an ever-lamented accident. But the truth was that he died from solitude, the enemy known but to few on this earth, and whom only the simplest of us are fit to withstand

Solitude from mere outward condition of existence becomes very swiftly a state of soul in which the affectations of irony and scepticism have no place. It takes possession of the mind, and drives forth the thought into the exile of utter unbelief. After three days of waiting for the sight of some human face, [he] caught himself entertaining a doubt of his own individuality. It had merged into the world of cloud and water, of natural forces and forms of nature. In our activity alone do we find the sustaining illusion of an independent existence as against the whole scheme of things of which we form a helpless part. [He] lost all belief in the reality of his action past and to come

Not a living being, not a speck of distant sail, appeared within the range of his vision; and, as if to escape from this solitude, he absorbed himself in his melancholy But at the same time he felt no remorse. What should he regret? He had recognized no other virtue than intelligence, and had erected passions into duties. Both his intelligence and his passion were swallowed up easily in this great unbroken solitude of waiting without faith

His sadness was the sadness of a sceptical mind.

from Nostromo, by Joseph Conrad

AUTHORS PREFACE

T O COMBINE the techniques of the novelist with those of the journalist is to tread on slippery ground. Henry James wrote of the danger to the novelist of the fatal futility of Fact; it is even more hazardous for the journalist to be lured into using the devices of dramatic fiction. There is a temptation to suppress inconvenient facts simply because they spoil the shape of the narrative, and to re-create imaginatively thoughts and attitudes of protagonists that can never be known with absolute certainty (how can one tell precisely what was in the mind of a sailor alone at sea?).

As far as possible, we have avoided these temptations. We have tried to record all the evidence, so that the reader, if he disagrees with our judgments, can form his own. We have allowed the story to unfold as a strictly documented chronology, supported by Donald Crowhursts own copious writings. At times, to make sense of a sequence of events, we have had to speculate about Crowhursts state of mind, and even about some of his actions but we have always tried to make it clear when we are doing so, and have avoided reaching firm conclusions except where overwhelmingly supported by the facts.

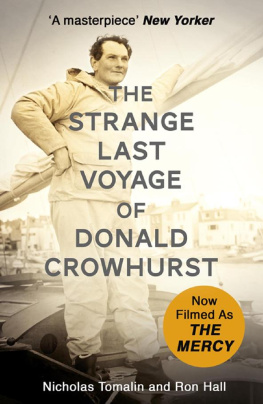

If, despite this rigorous approach, the book should have something of the flavour of a novel, it is simply because the actual sequence of events had the shape and inevitability of fictional tragedy. When the bare outline was first revealed in the Sunday Times of July 27th, 1969, it was at once recognised as a story of deep psychological complexity as well as sensational incident. It captured the imagination of the Press for many days, and Sir Francis Chichester referred to it as the sea drama of the century. At that time, however, we knew little about the personality of Crowhurst, and had read his logbooks only for external detail. As we investigated further, it emerged as one of the most extraordinary stories of human aspiration and human failing that, as journalists, we have ever had to record.

Although it is basically a story about heroics, there is no herobut neither is there a villain. Crowhurst, despite his deceptions, was a man of courage and intelligence, who acted as he did because of intolerable circumstances. The fact that he paid a far greater penalty than he need is testimony to his quality. We have fully convinced ourselves that the two main supporting figures in the ventureRodney Hallworth, the agent, and Stanley Best, the sponsorwere never knowingly parties to Crowhursts deceptions. (Nor, for that matter was anyone else.) Both have been outstandingly frank in discussing their involvement, and have opened their files to provide us with much valuable source material.

We have had similar excellent assistance from the boat-builders, John Eastwood and John Elliot. Although everyone admits that Crowhurst set off round the world unprepared, it was not the fault of Eastwoods, but of the whole confusion and rush that preceded the voyage (few boat-builders would have even attempted the task in such a short time). Eastwoods have generously agreed that, in the interests of historical completeness, Crowhursts various outbursts against the boat should be recorded in the book, though often they speak more of his state of mind than of the state of the boat. Most of the faults that did exist would have been avoided if there had been a normal time for building and trials.

We are indebted to many friends and acquaintances of Donald Crowhurst who gave up time to describe aspects of his life and his preparations for the voyage; in particular to Peter Beard, Ronald Win-spear, Edward Longman, Bill Harvey, Eric Naylor and Commander Peter Eden. We have received wise assistance in many matters from the Crowhurst family solicitor, T. J. M. Barrington.

We thank Cassell & Co, for permission to publish extracts from A World of My Own by Robin Knox-Johnston; Arthaud, Paris, for permission to reproduce some of Bernard Moitessiers writings; and Weidenfeld and Nicolson for permission to quote from The Image by Daniel Boorstin. Our thanks are particularly due to the BBC for providing us with transcripts of Crowhursts tape recordings, and to Donald Kerr and John Norman of the BBC South and West Region who volunteered their own testimony as actors in the drama.

Rupert Anderson, Receiver of Wrecks, Kingston, Jamaica, gave us enthusiastic help during our inspection of the boat after the voyage, as did his boatman Egbert Knight, who spent two days working with us in blistering heat. Captain Richard Box, of RMV Picardy which found Crowhursts boat, provided invaluable information.

On the immediate task of writing the book, we are indebted most of all to Captain Craig Rich, who spent several weeks investigating every aspect of Crowhursts navigational record, and prompted many important conclusions. Peter Sullivan was responsible for the detailed drawing of Teignmouth Electron, and Michael Woods for the maps. Robert Lindley, the Sunday Times correspondent in Buenos Aires, investigated Crowhursts secret landing in South America, and chapter 13 is based on his account. Ruth Hall undertook the difficult task of deciphering and transcribing Crowhursts logbooks, and offered many valuable suggestions, as did Claire Tomalin.