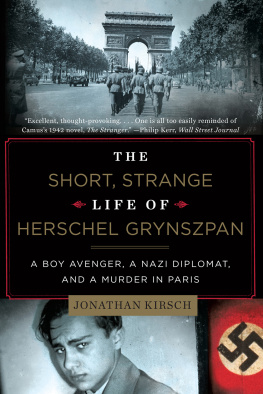

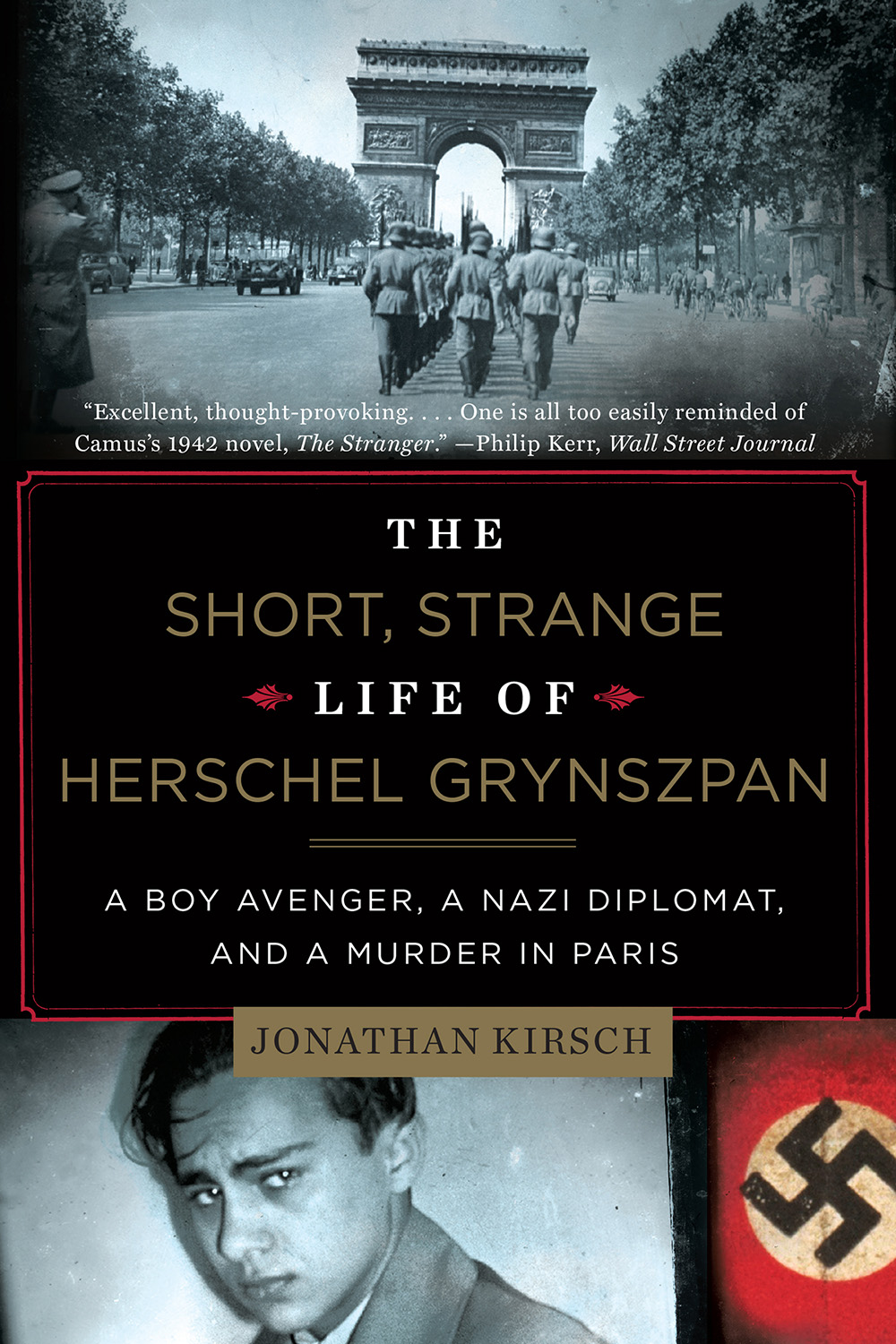

THE SHORT,

STRANGE

LIFE OF

HERSCHEL

GRYNSZPAN

A BOY AVENGER, A NAZI DIPLOMAT,

AND A MURDER IN PARIS

J ONATHAN K IRSCH

For my father, Robert

and my brother, Paul

and my father-in-law, Ezra Benjamin

and the mishpocheh for whom their memory is a blessing:

Ann, Adam, Jennifer, Remy, and Charles Ezra Kirsch

Marya and Ron Shiflett

Caroline Kirsch

Heather Kirsch

Joshua, Jennifer, Hazel, and Menashe Kirsch

CONTENTS

Part I

FROM HANOVER TO PARIS

Part II

INCIDENT ON THE RUE DE LILLE

Part III

PARIS TO BERLIN

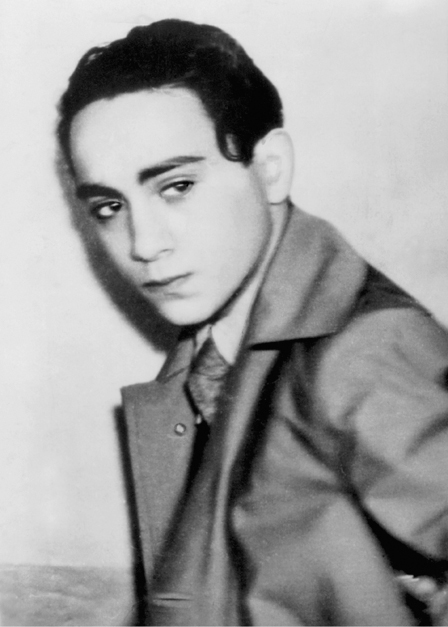

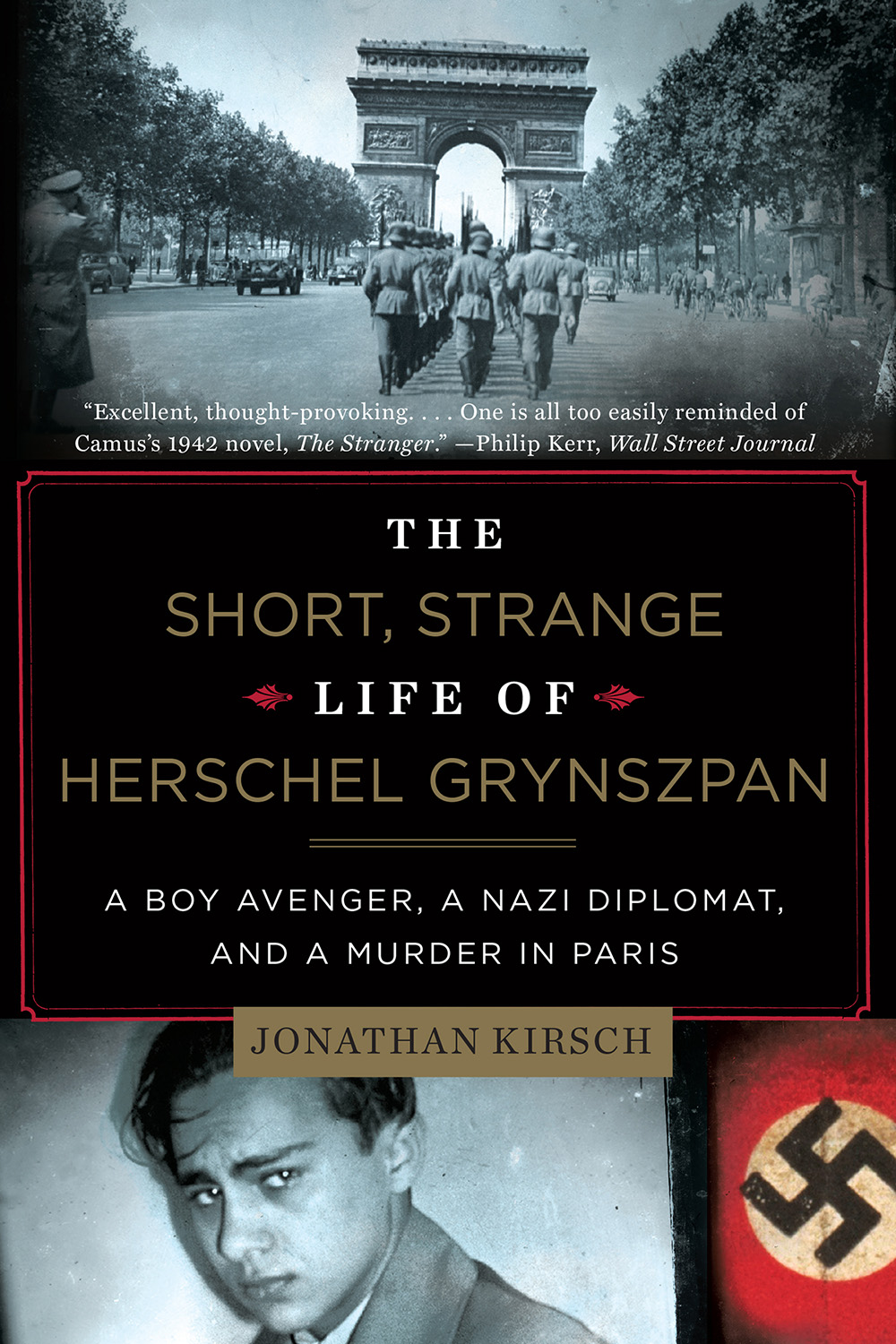

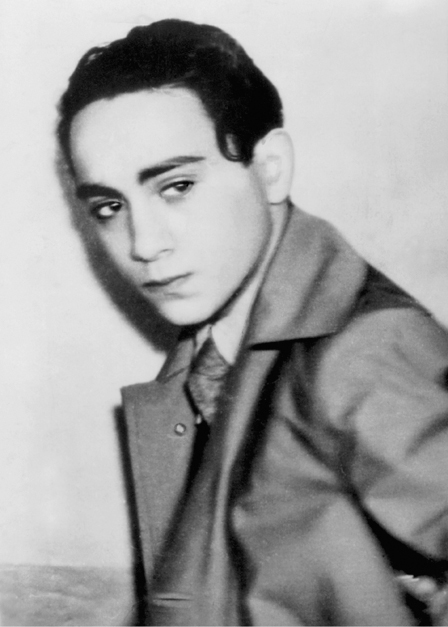

L IKE STILLS FROM A FILM NOIR, THE BLACK-AND-WHITE photographs of a seventeen-year-old boy named Herschel Grynszpan that have come down to uspolice mug shots, newspaper photos, a souvenir snapshot taken at a Paris street faircapture the various faces that he presented to the public during the fall of 1938.

With his hair brushed back off a high forehead, he seems to possess a certain swagger and style in some of the photographs. He is a diminutive but also darkly handsome fellow who was described in one official document as a fashion designer, and, in a few of the snapshots, he resembles a matinee idol.1 In others, he looks almost thuggish, like a little gangster dressed up in an expertly tailored suit. One candid photo, snapped through the window of a police car shortly after his arrest, portrays him as a lonely and frightened child. Yet all of these photos invariably depict the same human being, a troubled adolescent who boiled up out of a noisy Jewish neighborhood in a backwater of Paris and demanded the attention of the astonished world.

Laffaire Grynszpan , as his case came to be known, starts with a single act of violence behind the locked gates of the German embassy in Paris on November 7, 1938. But it is also a story replete with shock and scandal, mystery and perplexity. As in other and more recent episodes, the abundance of evidence does not rule out speculation. Was Herschel Grynszpan the cats-paw of an international Jewish conspiracy that sought to provoke a war between France and Germany, as Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels imagined? Was he an agent provocateur who was charged by his Gestapo handler with the task of ridding Germany of an anti-Nazi diplomat and, at the same time, providing the Nazi regime with a pretext for a major escalation in the persecution of the Jews, as philosopher Hannah Arendt suggested? Does he deserve to be regarded as a proto-hero of the sexual liberation movement even though he lived in an era when gay men were sent to the camps along with Jews and Gypsies?

Precisely what transpired inside the ornate German embassy in Paris on that day remains a puzzlement, but even more baffling is the black hole of history into which Grynszpan has fallen since the end of World War II. Herschel Grynszpan was briefly famous, and it was his fameor, as the Nazis saw it, his infamythat accounts for the trove of historical detail that is available to us today. We know how much he weighed, how tall he was, and how much money his family received in welfare payments because he was investigated by both French and German police officers, and he was examined by physicians, psychiatrists, and social workers in the service of the French criminal courts and later by their counterparts in Nazi Germany, all in the greatest and most intimate detail. Grynszpan, still only an adolescent, was questioned by the famously efficient interrogators of the Gestapo and even by Adolf Eichmann, a self-styled expert on Jewish affairs in the Nazi bureaucracy and one of the masterminds of the Final Solution.

Today, however, Grynszpan remains a mystery, an irony if only because Grynszpan was among the most famous inmates of the Nazi concentration camp system. The names and deportation dates for Jews who were sent from Paris to Auschwitz by the tens of thousands were meticulously recorded and preserved by the Nazis, but no such data is available for Herschel Grynzpan. Did he receive a quick death by Genickschuss in an interrogation cell at Gestapo headquarters in Berlin? Was he beheaded in the courtyard of a Nazi prison? Did he die in a German infirmary despite the frantic efforts of the SS doctors to keep him alive in case Hitler set a date for the long-delayed show trial in which Grynszpan was to play a starring role? Or did Grynszpan, as some have suggested, somehow survive the Second World War and show up in 1960 as a spectral figure in the public gallery of a German courtroom, where his unlikely life story was reprised?

Perhaps the most vexing aspect of the Grynszpan case is the fact that he has never been embraced as the heroic figure he earnestly sought to be. His fellow Jews, suffering through the catastrophic aftermath of his act of protest at the German embassy in Paris, generally disapproved of it as useless, dangerous, and a great disservice to Jews everywhere, according to Gerald Schwab, one of the principal investigators of the Grynszpan case.2 One of Grynszpans own attorneys, richly paid to defend him in the French courts, dismissed him privately as that absurd little Jew.3 Hannah Arendt pronounced him to be a psychopath and, even more shockingly, accused him of serving as an agent of the Gestapo.4 Jewish armed resistance against Nazi Germany is much studied and celebrated, but Grynszpan remains without honor even among the people whose avenger he imagined himself to be.

Grynzspan has indeed all but disappeared from the historical record. The first scholarly work on the Grynszpan affair, Der Fall Grnspan, an article by historian Helmut Heiber, was published in 1957 in the German language only. The one monograph on the Grynszpan case published in Englisha 1990 account by Gerald Schwab, an interpreter for the U.S. War Department at Nuremberg and a career employee of the U.S. State Department, who wrote a dissertation about the case for his masters degree at George Washington Universityis long out of print. A book-length biography of Grynszpan written in the early 1960s by a French physician, Dr. Alain Cunot, has never been published.

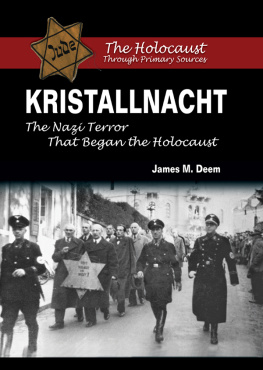

Herschel Grynszpan himself is mostly a missing person when it comes to the vast literature of the Second World War and the Holocaust. When Grynszpan is mentioned at all, it is only to note that his act of violent protest in Paris was seized upon by Joseph Goebbels, propaganda minister of the Third Reich, as a pretext for Kristallnacht, the pogrom that marked an escalation in Hitlers war against the Jews. At Yad Vashem, for example, a single grainy snapshot of Grynszpan appears for a couple of seconds in a slide show about Kristallnacht, and he is mentioned not all in the accounts of Jewish resistance to Nazi Germany.

The effacement of Herschel Grynszpan, who wrote and spoke so ardently about his deed to lawyers, judges, politicians, and reporters in the months and years following his arrest, would have broken the boys heart. His prison journals, which were carefully preserved and studied by both French and German authorities, reveal that the lonely and frightened adolescent yearned not merely for attention but for a place of consequence in the saga of the Jewish people. He thought the only end to isolation was to reach the point where he was no longer separated from the true struggles that went on around him, writes Don DeLillo of Lee Harvey Oswald in the novel Libra , but the same words surely apply to Grynszpan. The name we give to this point is history.5

Next page