Table of Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

ALSO BY STEPHEN KOCH

The Breaking Point: Hemingway, Dos Passos, and the Murder of Jos Robles

Double Lives: Stalin, Willi Mnzenberg, and the Seduction of the Intellectuals

The Modern Library Writers Workshop: A Guide to the Craft of Fiction

Double Lives: Espionage and the War of Ideas

The Bachelors Bride

Andy Warhol: Photographs

Stargazer: Andy Warhols World and His Films

Night Watch

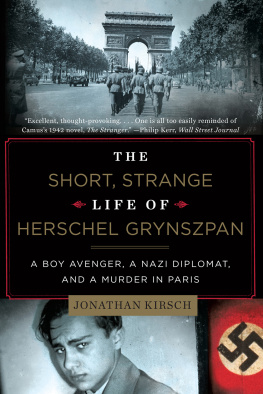

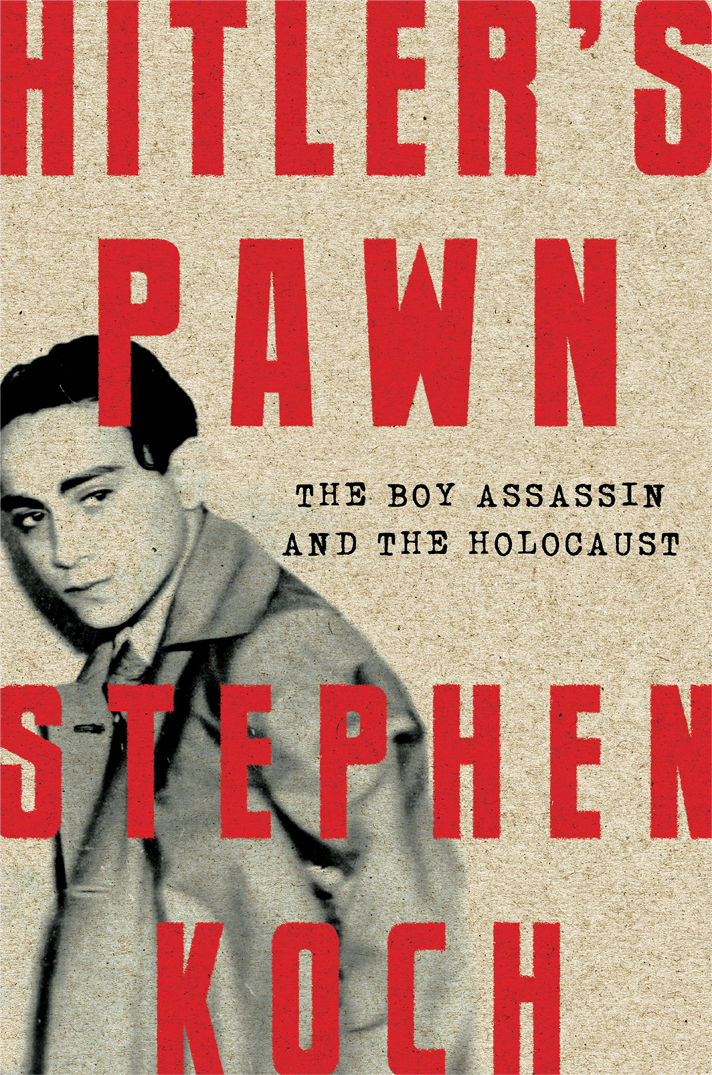

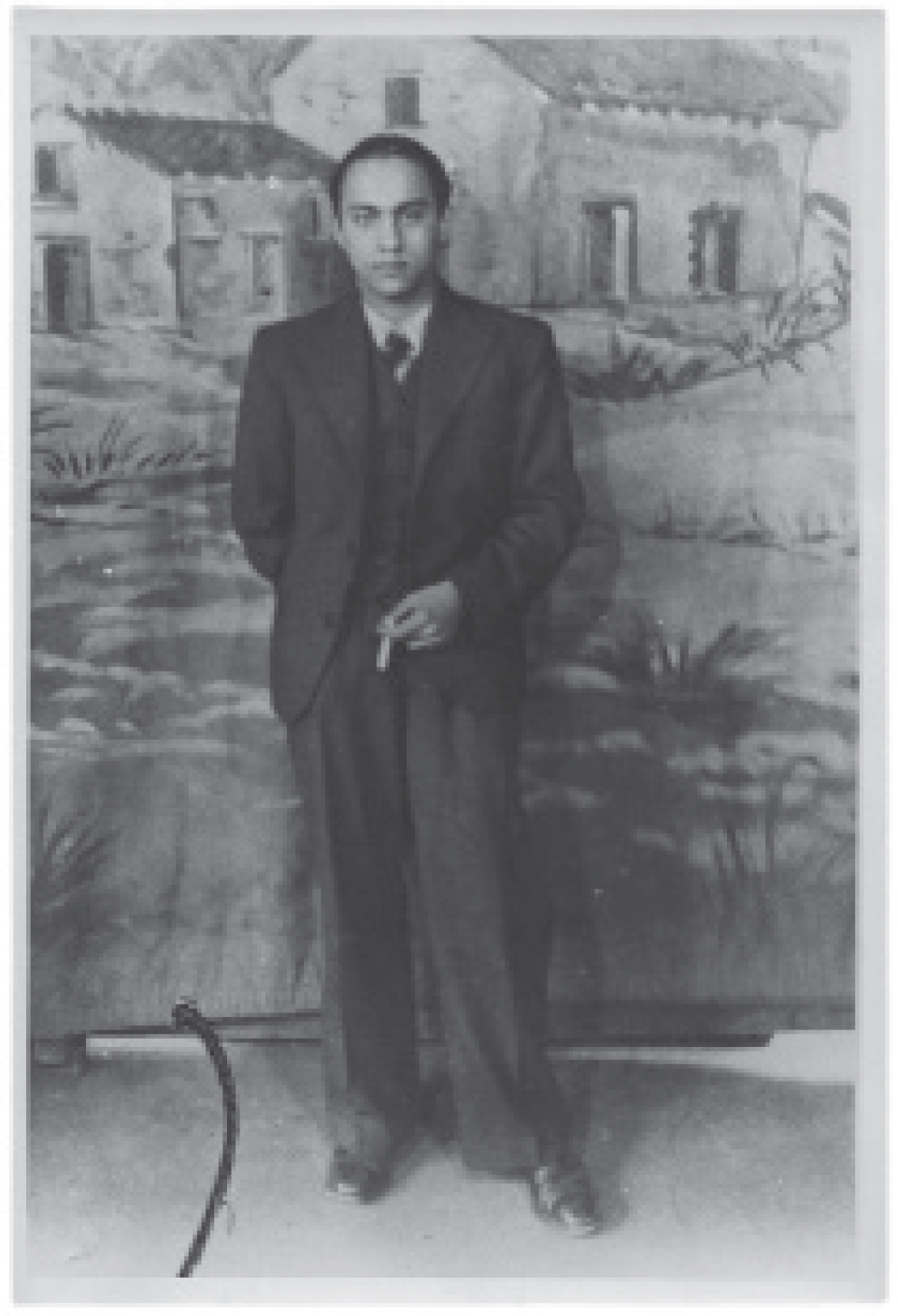

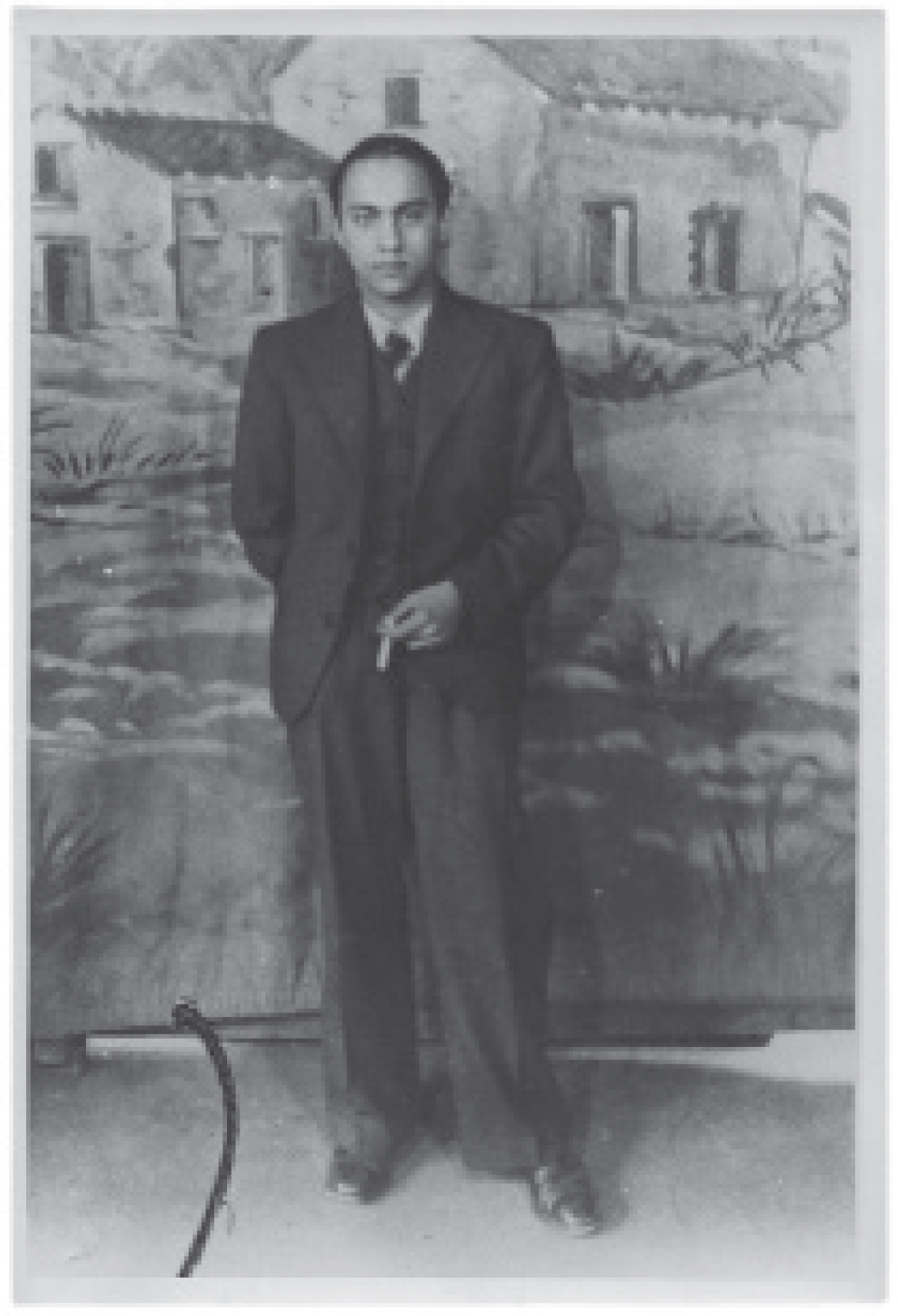

Postcard photo of Herschel Grynszpan, shortly before assassination

Hitlers Pawn

Copyright 2019 by Stephen Koch

First hardcover edition: 2019

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Koch, Stephen, 1941author.

Title: Hitlers pawn : the boy assassin and the Holocaust / Stephen Koch.

Description: First hardcover edition. | Berkeley, California : Counterpoint, c [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018018729 | ISBN 9781640091443

Subjects: LCSH: Grynszpan, Herschel Feibel, 1921approximately 1943. | Jewish refugeesFranceBiography. | AssassinsFranceParisBiography. | Vom Rath, Ernst, 19091938Assassination.

Classification: LCC DS134.42.G79 K63 2019 | DDC 940.53/18420092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018018729

Jacket design by Sarah Brody

Book design by Jordan Koluch

COUNTERPOINT

2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Printed in the United States of America

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

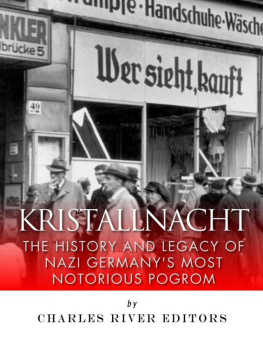

For Franny

On November 7, 1938, Herschel Grynszpan, an impoverished seventeen-year-old Polish Jew living in Paris, obsessed with Nazi persecution of his family in Germany and brooding on protest, revenge, and his own insignificance, bought a small handgun, carried it on the Paris Mtro to the German embassy, and, never before having fired a weapon in his entire life, shot down the first German diplomat he saw. When the wounded official died two days later, Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels used his death as their pretext for the great state-sponsored wave of anti-Semitic violence and terror known as the Kristallnacht, the pogrom many consider to be an initiating event of the Holocaust. Overnight, a perfect political nobody found himself world famous, a face on front pages everywhere, and a pawn in the machinations of great power.

But the pogrom of November 9, 1938, was not the end. It became Herschel Grynszpans destiny to play a role in the Second World War and the Holocaust unlike that of anyone else in the world. Until 1940, Herschels impending murder trial in Francenever heldmade him an icon in the battle of ideas between anti-Nazis and profascists in Europe and America. Hoping to save the boys life by using his trial to unmask Nazi anti-Semitic outrages, the great anti-Nazi journalist Dorothy Thompson founded a defense fund for him and hired the best lawyers in France to defend him. There was embattled controversy. Various conspiracy theoriesother than Hitlers ownflourished. Sexual and political rumors swirled around him. The Germans accused him of being a British agent. Some influential anti-Nazis even suspected he might be an agent of the Gestapo, set up to provoke the Kristallnacht.

When France fell in 1940, Herschel was forced into an entirely new role. Hitler dispatched an elite squad of the Gestapo to Paris to find Herschel Grynszpan, arrest him, and bring him to Germany alive. After a bizarre chase, the boystill a teenagerwas captured and flown in secret to Berlin, where he was held prisoner as the defendant in a massive show trial the Nazis designed to be a front for the mass murders that were about to begin. Its purpose: to prove that the Jews had started the Second World Warsparked by Herschels crime.

When the maturing Herschel realized that the Nazis were planning to use him against his people once again, he set out to use all his ingenuity to prevent this trial from ever taking place. Preparations for the trial were sinister, elaborate, advanced, and developed at the highest levels of the regime. Hitler was kept constantly informed. It became a duel of wits between one imprisoned Jewish youth and Joseph Goebbels and the Fhrer himself.

Yet Herschels story has been almost forgotten, shrouded in the boys own insignificance and twisted in myth and conspiratorial fantasy. His name appears for a few lines in any respectable history of the European war. Histories of the Kristallnacht usually grant him a chapter or two. There have been a few books about him in various languages (see A Note on Sources). Most are virtually unknown. Some are excellent. Some are fiction or dubious mixtures of fact and fiction. Some are scholarly but in places erroneous. Several are mired in false information or out-of-date research. For decades, mystification persisted. Herschel Grynszpans crime was a simple one, but it was only in 2013seventy-five years after the shots were firedthat definitive clarity was finally achieved.

This is his story.

Fondling another glass of bon vin rouge, the exhausted premier of France tried without success to relax into his planes plush seat. He was flying home from Germany after signing what history would come to condemn as the Munich Pact. It was October 1, 1938, as the two-engine, twenty-eight-seat Air France luxury airliner flew westward into the declining European afternoon. This was not the premiers first glass of red for the day, nor would it be his last. douard Daladier was normally an abstemious man, but some suspected that he had signed the actual agreement itselfthen seen as the salvation of civilizationin a state of less-than-perfect sobriety. The premier was desperately unhappy.

Daladier was a stubby, deceptively tough-looking politician from the South of France. He had a wide, square, stolid face, and within twenty-four hours, countless newsreels would show the world that he was the shortest leader among the four at the meeting he had just left: shorter than Hitler and Benito Mussolini, and much shorter than the British prime minister, Neville Chamberlain. With his thick neck, heavy head, and implacable brow, Daladiers political nickname was the Bull of Vaucluse. He looked toughfearless, decisiveand that look had helped elect him.

Looks deceived. Daladier was an intelligent man, and in contrast to Neville Chamberlain, he was not wrong about Hitler. Chamberlain believed that it might be possible to treat Hitler as a normal politician. Daladier did not. His assessment of the Nazi threat to his country and the world was lucid to the point of clairvoyance. He knew who Hitler was. Knowing that, he also knew that he had just played a losing hand in Munich. The night before, he had signed away part of the stature and power of France. He had signed because he was indecisive and doubted that France could face down Hitler with a threat serious enough to frighten the tyrant. He was afraid that a second world war would begin on his watch.

Next page