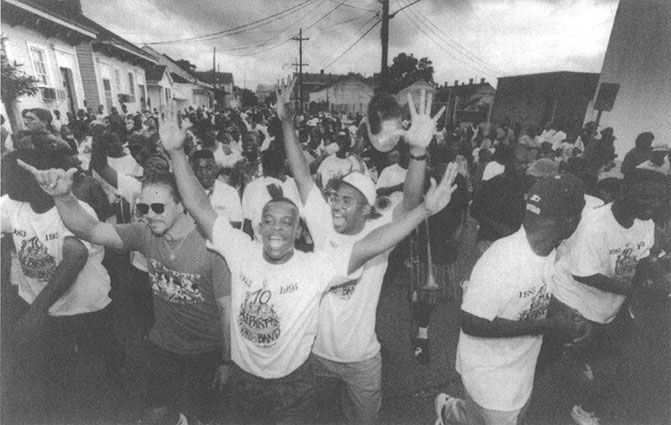

KEEPING THE BEAT ON THE STREET

Rebirth Brass Band Photo by John McCusker. Courtesy Hogan Jazz Archive, Tulane University.

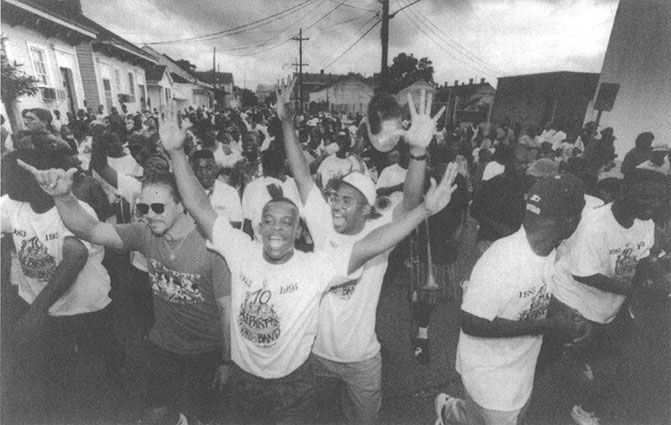

Majestic Brass Band (Joe Taylor, Jerome Davis, Flo Anckle) Photo by Marceljoly

The people got the soul. We dont have it. They always say, The band got the soul.

We dont have no soul. The people got the soul.

FLOYD FLO ANCKLE, leader, Majestic Brass Band

KEEPING THE BEAT

ON THE STREET

The New Orleans

Brass Band Renaissance

MICK BURNS

LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS

BATON ROUGE

Published by Louisiana State University Press

Copyright 2006 by Louisiana State University Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

LOUISIANA PAPERBACK EDITION, 2008

FIRST PRINTING

DESIGNER: Andrew Shurtz

TYPEFACE: Tribute

PRINTER AND BINDER: Thomson-Shore, Inc.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Burns, Mick, 1942

Keeping the beat on the street : the New Orleans brass band renaissance / Mick Burns,

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ), discography (p. ), and index.

ISBN 0-8071-3048-6(cloth : alk. paper)

1. Bands (Music)LouisianaNew Orleans. 2. JazzLouisianaNew OrleansHistory and criticism. J. MusiciansLouisianaNew Orleans. 4. New Orleans (La.)Social life and customs. I. Title.

ML1311.8.N48B87 2005

784.9l65'0976335-dc22

ISBN 978-0-8071-3333-0 (paper : alk. paper)

Published with support from the Louisiana Sea Grant College Program, a part of the National Sea Grant College program maintained by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration of the U.S. Department of Commerce.

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

To the memory of Anthony Tuba Fats Lacen

Contents

Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Thanks and acknowledgments are due to

The Board of Directors of the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Foundation, Executive Director Wali Abdel Raoof, Program Director Sharon Martin, and Archivist Rachel Lyons, for their support and contributions

The Lincolnshire County Council

Jazzology Press, for permission to reprint passages from my book The Great Olympia Band

New Orleans Music, for permission to reprint Anthony Lacen: Goodbye Tuba Fats

The New Orleans Jazz Commission and the New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park

The William Ransom Hogan Jazz Archive at Tulane University, Curator Bruce Boyd Raeburn, and Lynn Abbott and Alma Williams Freeman

The Amistad Research Center at Tulane University, Director of Archives Brenda Square, and Heidi Dodson

Parker Dinkins, Peter Nissen, Brian Wood, Bill Bissonette, Emile Martyn, Anthony Lacen, and Helen Regis

Marcel Joly, Bill Dickens, Butch Gomez, Mike Casimir, Leroy Jones, Dave Cirilli, and Mike Peters, who provided photographs

Holly Hardiman, who helped with the index

The musicians and citizens of New Orleans, who gave freely of their time for interviews so that this story could be told

Barry Martyn, whose assistance was invaluable

Louisiana State University Press and editor George Roupe

KEEPING THE BEAT ON THE STREET

Introduction

The early years of the twentieth century saw the explosive beginnings of the most culturally significant American art form, jazz. The influence of this creative phenomenon born in New Orleans changed things for ever. The whole spectrum of music, from Tin Pan Alley to musical shows to Stravinsky and Shostakovich, reflected the spirit and sound that first found expression on the streets of a city in southern Louisiana. Louis Armstrong, Sidney Bechet, Kid Ory, and King Oliver achieved considerable personal success outside the city. But they were the most visible members of a larger diaspora that carried the new music not only across America but to London, Paris, Cairo, Moscow, and Beijing. Almost all the practitioners of this new art form found a cradle for their burgeoning talents in the brass bands, which had been around for decades before jazz began. One hundred and thirty years later, the brass bands of New Orleans still perform the same function they always did and still provide a crucible for the seemingly inexhaustible supply of creative fire that is New Orleans music.

According to contemporary accounts, the first black brass bands in New Orleans appear to have hit the streets in the 1870s. Typically consisting of nine or ten pieces, they played whatever they could get hired to playdignified sonorous dirges for funerals, sprightly military marches for parades, and popular hits of the day for dances and concerts. At that time, the brass band movement, mostly fueled by amateur musicians, flourished all over America and Europethere were bands attached to villages, churches, factories, plantations, and coal mines; they served as a creative outlet for the working man and a symbol of celebration and solidarity for their communities.

In the beginning, there probably wasnt much difference between a brass band in New Orleans and, for example, northern EnglandShepherd of the Hills played competently from a written score is going to sound very similar wherever it happens. What makes New Orleans brass band music unique is the way the musicians started with the same ingredients as everyone else and transformed them into a vital art form. Today, a brass band in New Orleans will kick off on a bass lick, play a continuous collective improvisation (no written music) and keep it going for as long as forty minutes. In northern England, the brass bands are still reading Shepherd of the Hills.

How did this happen? In the absence of recordings, we have to rely on contemporary accounts for the start of the process. According to Richard Knowless excellent book Fallen Heroes (Jazzology Press) the emerging hot style of playing first appeared in a brass band context with the Tuxedo Brass Band, under the leadership of trumpet player Oscar Celestin, sometime after 1910.

Celestin also led a hugely popular dance band, and many of the citys top players (including some early jazz legends) worked for both organizations. We can only speculate on the extent to which improvisation and swing appeared on the street in those early days, although King Olivers 1923 recording of the march High Society offers a broad hint.

In 1929, a film newsreel soundtrack captured the first recorded sound of a New Orleans brass band playing at a Mardi Gras parade. Although theres only a brief snatch of muffled music, a unique Crescent City characteristic can clearly be heardthe seductive, propulsive rhythmic device called the second line beat.

In simple terms, this describes a syncopated pattern on the bass drum that may be phonetically rendered as Dah, Dah, Dah, Didit, Da! Transfer this rhythmic feel to the horns, and the whole band swingsit makes you want to dance. Of course, there were many bands who could play both written music for formal events and, for want of a better word, improvised swing for the dancing crowd. Bands that couldnt, or didnt, read music, were dismissively called tonk bands by more formally inclined musicians. But it was the ability and inclination to depart from the written score that made New Orleans brass bands so special. In a sense, you could describe the whole creative evolution of brass band music as the triumph of tonk.

Next page