Table of Contents

FOR THE ANCESTORS

Lynn Burks

Shawn Burks

Eric Claytor

Richard Claytor

Kelsie Foreman

Lamonte Foreman

Ophelia Foreman

Zedock Foreman

Reginald Gougis

Andre Jones

Shirley Kennedy

James London

Horace Maxie

Ruth Maxie

Shirley Maxie

George Parker

James Turner Jr.

Mavis Turner

Evelyn Tynes

Jackie Tynes

Catherine Weaver

David Weaver

Horace Weaver

FOR

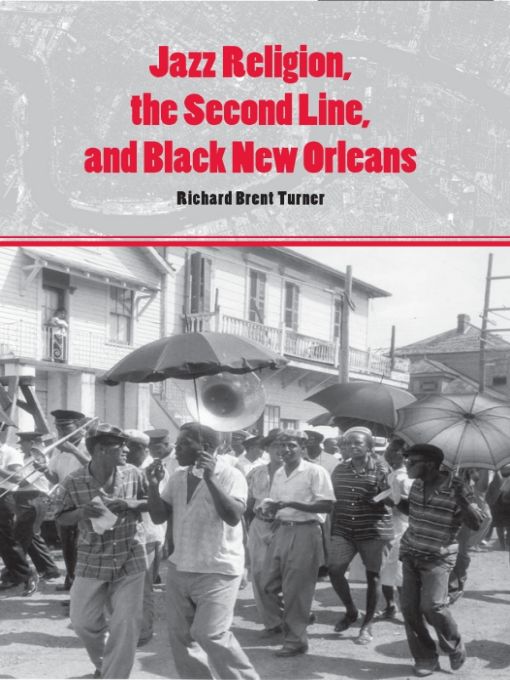

Social justice in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina

PREFACE

The inspiration for this book can be traced to Sidney Bechets reflections about New Orleans music in Treat It Gentle: An Autobiography: jazz is there in that bend in the road in the American South and you gotta treat it gentle.

The road to the music in Jazz Religion began in my hometown, Boston, Massachusetts, in the 1950s with the fascinating stories of the southern branch of my family in North Carolina that my mother, Mavis Turner, and my aunt, Kelsie Foreman, recited to me when I was a young boy. The exciting and mysterious life of my grandfather, Zedock Foreman, the handsome child of a former slave and former slave owner was at the crossroads of those southern stories that eventually brought me back home to the South, to my familys roots.

My teachers at Princeton University also enabled this books publication with the excellent resources they provided in the 1980s. Thanks to John Wilson, who directed my Ph.D. program in the religion department, for including seminars in African religions with James Fernandez in anthropology and Ephraim Isaac at Princeton Theological Seminary. A reading course with Albert Raboteau in 1983 introduced me to his brilliant book, Slave Religion: The Invisible Institution in the Antebellum South, Melville Herskovitss The Myth of the Negro Past, and a career-long fascination with African continuities in African American religions.

I have been blessed with the advice of several brilliant extramural colleagues in the field of New World African religions. Claudine Michel at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and Patrick Bellegarde-Smith at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, published shorter versions of my book chapters in the Journal of Haitian Studies. They welcomed me to the Board of Directors of KOSANBA, a scholarly association for the study of Haitian Vodou, in 2007, and provided critical feedback for the papers I read at KOSANBAs international colloquia in Boca Raton, Florida; Detroit, Michigan; and Boston, Massachusetts. Special thanks are due to George Lipsitz at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who read my book manuscript for Indiana University Press and provided important suggestions to improve the final product. To Lindsey Reed, I express thanks for brilliant editorial assistance, and Mitch Coleman did a great job with the word processing of the manuscript. It is always a professional pleasure to work with Robert Sloan, the editorial director of Indiana University Press.

DePaul University in Chicago awarded me a Faculty Research and Development Committee Grant, a Competitive Research Grant, and a Humanities Center Fellowship to begin the archival research for Jazz Religion from 1999 to 2001. The University of Iowa, one of the leading public research institutions in the United States, provided generous support to complete the research and writing of this book. During my years on Iowas faculty, I received two Arts and Humanities Initiative Grants (2002-2003 and 2005-2006) from the Office of the Vice President for Research and a Career Development Award (fall 2006) from the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences that gave me the funds and release time from teaching to conduct research at William Ransom Hogan Jazz Archive at Tulane University, the Historic New Orleans Collection, the New Orleans Public Library, and the Backstreet Cultural Museum. My second Arts and Humanities Initiative Grant allowed me to travel to New Orleans to attend Big Chief Allison Tootie Montanas jazz funeral in July 2005a few weeks before Hurricane Katrina devastated the city. Finally, blessings go out to all the brave New Orleanians who survived Hurricane Katrina. I am still a New Orleanian, and I love my city!

INTRODUCTION

Follow the Second Line

No matter where its played, you gotta hear it starting way behind

you. Theres the drum beating from Congo Square and theres the

song starting in a field just over the trees. The good musicianeer...

hes finishing something... that started back there in the South. Its

the remembering song. Theres so much to remember.

SIDNEY BECHET, TREAT IT GENTLE

Personal Introduction

I arrived in New Orleans on a hot Saturday evening in August 1996 to begin a new job in the theology department at Xavier University. I was not a total stranger to the vibrant culture of the Crescent City. The Parkers, a large African American family that had befriended me during my years in San Francisco and Santa Barbara, California, had introduced me to their extensive New Orleans family network. Their New Orleanian relatives found an orange shotgun house for me to rent on Cambronne Street, in the heart of the uptown riverbend neighborhood where the St. Charles streetcar line turns into Carrolton Avenue. This neighborhood is famous for its graceful architecture, Creole restaurants and coffee houses, and its music. Across the street from my new residence was St. Joan of Arc, a small black Catholic Church with a gospel choir that often sang so irresistibly that their practice sessions drew me out of the house and into the street to celebrate the spirit of their soulful sounds. As I walked up Cambronne Street at 10 oclock on my first night in New Orleans, my senses were overcome with the smells of southern-fried cooking from Andrs Creole Restaurant, and the sounds of live music in the air. When I reached dark and narrow Oak Street, I saw where all the noise was coming from, and I entered the Maple Leaf Bar. The Maple Leaf is one of those old neighborhood clubs where New Orleanians of every race, color, and style gather on certain nights of the week to party and dance to the music of the Dirty Dozen and Rebirth brass bands. Members of these bands perform in what are known as second lines, the jazz street parades and processions of black New Orleans that follow the first procession of church and club members, secret societies, and grand marshals. On that Saturday, I partied all night and into the wee hours of Sunday morning.

The next day, after a Sunday brunch of hot beignets (freshly fried donuts sprinkled with powdered sugar) and caf au lait at Caf du Monde in the French Quarter, my friends led me to a second-line performance in the streets of TremNew Orleans oldest black neighborhood, which begins on the far side of Rampart Street, at the edge of Louis Armstrong Park and Congo Square. We walked in funky rhythm with hundreds of black people who danced and partied to the music of a neighborhood jazz brass band that wound its way through the city for several hours in the humid afternoon heat. When we came to Esplanade Avenue, I asked a native New Orleanian in the crowd where the parade was going, and he said, in a melodic southern accent, Just follow the second line, baby, and youll see. Much later, the second line dispersed in front of the Circle Seven Market on St. Bernard Avenue, where people had set up their grills to sell barbeque, ribs, sausage, potato salad, and red beans and rice.

Next page