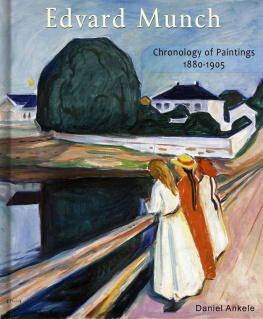

Ankele - Edvard Munch: Chronology of Paintings 1880-1905

Here you can read online Ankele - Edvard Munch: Chronology of Paintings 1880-1905 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: Ankele Publishing, LLC, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Edvard Munch: Chronology of Paintings 1880-1905

- Author:

- Publisher:Ankele Publishing, LLC

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Edvard Munch: Chronology of Paintings 1880-1905: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Edvard Munch: Chronology of Paintings 1880-1905" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Ankele: author's other books

Who wrote Edvard Munch: Chronology of Paintings 1880-1905? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Edvard Munch: Chronology of Paintings 1880-1905 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Edvard Munch: Chronology of Paintings 1880-1905" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Edvard Munch Chronology of Paintings 1880-1905 By Daniel Ankele Copyright 2015 Ankele Publishing, LLC ArtistLight.com All Rights Reserved Biography by

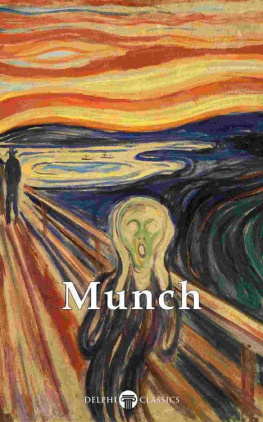

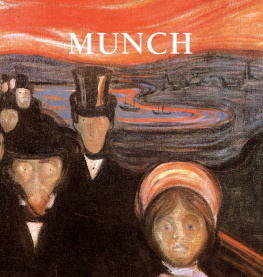

David A.J. Reynolds The sick girls fevered head rests benignly on the pillow, while a woman bows low in sorrow by her side. It is a scene of great pathos and strange serenity. The weary resignation in the girls eyes as she turns toward her stooped guardian leave us in no doubt that death is the unseen third character of the picture. The young artist knew it too as he painted it in his home, seated upon the wicker chair his sister had died on nine years earlier. Munchs mother died of tuberculosis at Christmas when he was just five years old.

And even though his aunt moved in to take care of his father and the five children, little Edvard and sister Sophie clung to each other like soul mates. In the following years, cramped within their close quarters in working class Oslo (then Kristiania), frail Edvard was frequently ill himself, often spending half the dark winter confined to bed. But just as she was approaching womanhood, it was Sophie, not Edvard, who followed her mother, succumbing to the dreaded disease. Once more the family was gathered around a dying loved one, pious fathers hands clenched together in prayer and Edvard silent in his stunned impotence. Sophie begged him to take the ailment from her, as if he was Jesus Christ; he hid behind the curtains to weep. In her final moments Sophie asked to be helped into a chair, where she was propped up like the girl in the painting.

That wicker chair was with Edvard until he died six decades later. Sophies death was a blow from which Edvard never fully recovered, biographer Sue Prideaux concludes. A desolate longing for her remained all is life; he had lost his mother all over again. But that her death found its way into his art time and again, constantly re-experienced, is not only a token of its deep imprint on his psyche. It also is a crucial insight into why Munch was an artist. As Arnold Weinstein puts it, art kept Munch alive and he knew it.

In Munchs own words, my sufferings are part of myself and my art. They are indistinguishable from me, and their destruction would destroy my art. More even than most artists, therefore, Munchs art, life-motivation, and inner pain were inextricably co-dependent. So, we return to that all too poignant scene being painted by the twenty-two year old Munch. How would he depict it? There had been other pictures of dying children, including one by Munchs friend and supporter Christian Krohg. But the motif was neither motivation nor explanation; his own expression would, as the world would discover, be idiosyncratic.

As the girla neighborand his aunt (representing herself) took their positions in front of Munchs easel, he saw something that vanished when I tried to paint it. Munch spent a year repeatedly re-painting the scene, looking for the inexpressible that he had seen and felt. The final result was hazy, demonstrating his sensation of seeing the image through his own closing eyelashes, and streaked with paint in parallel with the tears he shed looking at it. Few painters have ever experienced the full grief of their subject, Munch stated presumptuously yet probably accurately, as I did in The Sick Child . Unsurprisingly, however, when this most personal of projects was exhibited later that year (1886), Oslo did not appreciate Munchs vision. For the people of his home town, The Sick Child was nothing more than sloppy dilettantism; it represented everything respectable society despised in its precocious bohemian set.

Nevertheless, in Munchs eyes, it was a breakthrough in my art. Most of what I have done since had its birth in this picture. The disdain and ridicule that met his latest picture was not new and would continue to frame his efforts for years to come. In other ways too, these wild days in the Norwegian capital set patterns within which Munch was to live. The sorrows, sickness, and solitude of his childhood had taught the sensitive Edvard to distance his inner and outer selves and, therefore, in his youth he both ran from and held onto his upbringing. He ran from it into the arms of an impatient crowd eager to dispense with bourgeois mores, express themselves vigorously, and smash taboos in their wake.

Nevertheless, Edvard remained a polite and pensive presence among these comrades and, unlike them, was not busy burying his past but nursing it in the service of his art. Even as he regularly drank himself into a torpor with his friends, Edvard was both part of and on the cusp of the crowd. An inescapable element of the bohemian spirit of fin-de-sicle Europe was sexual promiscuity. It was a world which the fearful Edvard was ill-prepared to navigate. Munch was a strikingly handsome man and his nobly contemplative air only increased the attraction. Too courtly and cautious to pursue, he found himself both admired by and attracted to a series of women who were in open marriages.

This proved disastrous for Edvard, transitioning him from stunted and bereaved childhood relationships into confusing and humiliating adult intimacies. The effect, as is always the case with Munch, is best seen in his art. The painting Ashes (1894) depicts the emotional aftermath of that first sexual encounter in the 1880s, with the married Millie Thaulow unperturbed and provocative while Munch cowers in shame; his face and hand a putrid shade of green. Munchs portrayals of women in this period are often powerfully erotic and juxtaposed with an impotently downcast male figure. Modern critics tend to categorize that as misogyny, but the label is unfair and misses the point. Firstly, contemporaries consistently describe Munch as unusual in his gentle courtesy to women.

Secondly, he was portraying his own experience, unfortunate and unrepresentative though it may have been. As soon as the liaison was in place she considered me to be an objectbelonging to her, Munch remembers another, like a boy puppet she had gotten under the Christmas tree as a child. Though artistically prolific, these were also days of constant financial struggle. So it was a break when Munch received a state grant in 1889, enabling him to travel to Paris for further studies. As Edvards ship pulled away from the Oslo harbor, his father waved him goodbye in his best suit. It was the last time the two would see each other.

When Munch received word from his aunt of his fathers death, it sent him into a fresh spiral. A kind and generous man, Christian Munch was also, in his sons words, temperamentally nervous and obsessively religious to the point of psychoneurosis. Therefore, Christian bequeathed to his sensitive son a host of anxieties and terrors, which overshadowed Edvard as an adult along with his other fears and phobias. Nevertheless, Edvard never took the short-cut of casual contempt. His father was from a prominent and intellectual family, yet had blazed his own poorer and harder path as a doctor; he was no caricature tyrant. So, we find Edvard pacing the streets of Paris, for once bemoaning his distance from kin.

The anguish was not merely the familiar feeling of loss. Art, Munch reflected, was the outcome of dissatisfaction with life in my art I attempt to explain life and its meaning to myself. But his distance from this heart-rending event rendered him incapable of fashioning the artistic response that his heart and mind required. The breakthrough came with two fleeting experiences and commensurate conclusions, which became knownafter the Paris suburb where he livedas the Saint-Cloud Manifesto. The first idea was crucial in allowing him to make truce with the haunting spectre of death, while also reconciling his fathers belief in heaven and his own soulful agnosticism: nothing ceases to exist there is no example of this in nature, Munch states, nothing will perish and that is eternity. And so in the stunning vision of Night in St.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Edvard Munch: Chronology of Paintings 1880-1905»

Look at similar books to Edvard Munch: Chronology of Paintings 1880-1905. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Edvard Munch: Chronology of Paintings 1880-1905 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.