Text: Elizabeth Ingles

Layout: Baseline Co Ltd

61A-63A Vo Van Tan

th Floor

District 3, Ho Chi Minh City,

Vietnam.

Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

The Munch Museum/ The Munch-Ellingsen Group/

Artists Society (ARS), NY

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-78160-615-5

Edvard Munch

Landscape, Maridalen, near Oslo, 1881.

Oil on wood, 22 x 27.5 cm.

Munch Museum, Oslo.

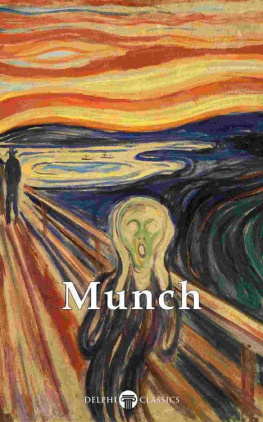

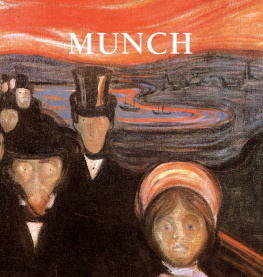

The name of Edvard Munch conjures up, for most people, one irresistibly memorable picture: The Scream , a shriek of stomach-churning terror uttered by a cringing figure with a skull-like face outlined against a fiery, blood-red sunset. This iconic image has come to epitomise the angst embodied in the Expressionism of the late nineteenth century. Yet its creator, a gentle soul given to introspection and self-analysis, lived to see his eightieth birthday and witnessed the world-wide critical acceptance of the Expressionist movement which he had been largely instrumental in initiating. Somehow one imagines that the originator of so graphic an image of fear would be too delicate and unworldly to survive the violent upheavals of the early twentieth century, but, although he suffered terribly from depression and anxiety for the greater part of his life, Munch was able to find a mode of living that enabled him to produce a large body of psychologically penetrating, disturbingly beautiful work. He was born in 1863 to a frail young mother, Laura Bjlstad, and her older husband, Christian Munch, a doctor; the following year the family moved to Kristiania, as Oslo was then called. There were five children altogether, of whom Edvard was the second-born and elder son. Early on Munch understood that he had a difficult twofold heritage to contend with: the physical threat of tuberculosis, which carried off first his mother and then his eldest sister, and the faint but distinct possibility of mental instability. Laura Munch died at the age of thirty, shortly after the birth of her fifth child. The effect on the family may be imagined. The father suffered most acutely, the younger children carrying only the haziest memories of their mother into later life. But the consciousness of loss never left them.

His fathers religiosity became more pronounced after Lauras death, to the point where the childrens anxiety about offending against Christian principles instilled in them a palpable fear of eternal damnation. The unhappiness of his childhood experience of death was compounded by his fathers unpredictable behaviour. Munch and his brother and sisters were never quite sure how their fathers fanatical piety was going to manifest itself but they could rely on the fact that they would be made to feel inadequate either as dutiful Christians or as obedient children. At times Dr Munchs playful nature, suppressed almost totally by his sadness at the death of his young wife, would resurface briefly and he would play with his children like any normal father. But then the blackness would reassert itself, and he would lash out violently. Indeed, in later life Munch would write that his father became almost insane for short periods. This must have been quite terrifying for a sensitive, quiet young boy who was himself prone to frequent bouts of illness. The death of his sister Sophie, the eldest child, when Edvard was thirteen, caused him even more profound suffering than had the loss of his mother when he was five. He watched anxiously as his father prayed over the girl, unable to do anything for her. To him, and to Sophie, Dr Munchs promises of eternal heaven meant nothing compared w ith her burning desire to live.

Girl Lighting a Stove, 1883.

Oil on canvas, 96.5 x 66 cm. Private Collection.

Old Aker Church, 1881.

Oil on canvas, 16 x 21 cm. Munch Museum, Oslo.

Her struggles were unbearable to watch. Edvards utter helplessness and sorrow were channelled some years later into a painting that he returned to obsessively: the marvellous The Sick Child , the first version of which was executed in 1885-6. (There were to be six versions altogether, created at roughly ten-year intervals.) In this large painting, almost four feet square (120 cm), he struggled throughout his life to express what he felt so intensely about his sisters death. During her last illness she repeatedly pleaded for help, for relief from pain neither Edvard nor his doctor father was able to provide it. This incapability was transformed into a feeling of guilt that he had survived and she had not. His attempts to put himself in her place in the picture were doomed to failure, just as he had failed to take her place as she lay dying. To the end of his life he was unable to resolve this. His guilt is poured into the picture, which is almost unbearably poignant. The young girls face is already a ghost, almost disembodied as she silently yearns to go on living. With its deep layers of meaning and evocation of the state of the artists soul, this can fairly be termed one of the first Expressionist paintings. He himself termed it a breakthrough in his style, and the collector and critic Jens Thiis, later Munchs biographer, called it the first monumental figure painting in our Norwegian art.

The Sick Child, 1896.

Oil on canvas, 128.5 x 118.5 cm.

The emphasis on religious piety, which appeared to do not the slightest good, as prayers for the life of mother and sister went unheeded, and the authoritarianism of a father who punished disproportionately for the most minor transgressions, came together in Munchs mind to give him a view of God as unjust, full of anger and entirely without compassion. Although he did not dare to contradict his father by refusing to go to church, by the time he was in his early twenties he had reached the conclusion that God did not exist, and that there was no eternity. This belief in the non-existence of God remained broadly unaltered throughout the rest of his life, though he changed his mind about the possibility of a continued existence in a kind of afterlife. With some bravery, Munch took the decision to become a painter in the face of his fathers firm preference that he should study engineering. His father reluctantly acceded, on the advice of a draughtsman friend. One of Munchs earliest self-portraits, from a year or so later ( Self-Portrait , 1881-2), shows a young man of sensitive, even sickly aspect, his large pale face, full curving lips and sloping shoulders giving little cause to credit him with any kind of physical or mental toughness. Yet there is, in the clear gaze, something of a challenge to the onlooker who might thus dismiss him.

Next page

![Scholtz - Munch: [#trendygoodfood]](/uploads/posts/book/234356/thumbs/scholtz-munch-trendygoodfood.jpg)