The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

CONTENTS

for my kids, Jack and Roisin

No place on Earth offers greater security to life and greater freedom from natural disasters than Southern California.

Los Angeles Times, 1934

THE DIALECTIC OF ORDINARY DISASTER

Once or twice each decade, Hawaii sends Los Angeles a big, wet kiss. Sweeping far south of its usual path, the westerly jet stream hijacks warm water-laden air from the Hawaiian archipelago and hurls it toward the Southern California coast. This Kona storm systemdubbed the Pineapple Express by television weather reportersoften carries several cubic kilometers of water, or the equivalent of half of Los Angeless annual precipitation. And when the billowing, dark turbulence of the storm front collides with the high mountain wall surrounding the Los Angeles Basin, it sometimes produces rainfall of a ferocity unrivaled anywhere on earth, even in the tropical monsoon belts.

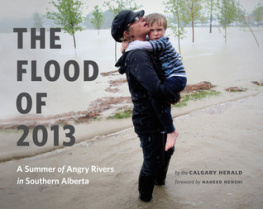

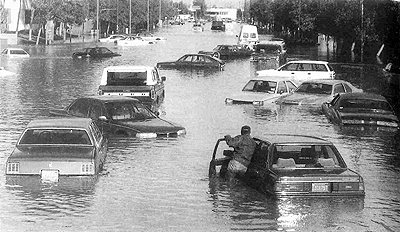

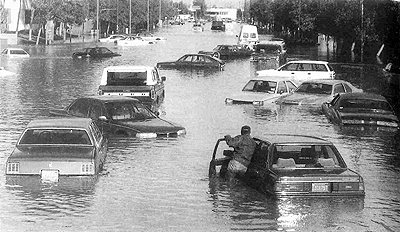

The two-week-long Kona storm of January 1995 differed little from the classic pattern, except perhaps in the unusual intensity of rainfall in the South Bay areaforcing the evacuation of low-lying neighborhoods in Long Beach, Carson, Torrance, and Hawaiian Gardensand in Santa Barbara County where 10 inches of rain fell in 24 hours. Otherwise, the scenes were those of ordinary, familiar disaster: Power was cut off to tens of thousands of homes. Sinkholes mysteriously appeared in front yards. Waterspouts danced across Santa Monica Bay. Several children and pet animals were sucked into the deadly vortices of the flood channels. Reckless motorists were drowned at flooded intersections. Lifeguards had to rescue shoppers in downtown Laguna Beach. Million-dollar homes tobogganed off their hill-slope perches or were buried under giant landslides.

January 1995 storm (Long Beach)

1. APOCALYPSE THEME PARK

[Southern California], often to its own surprise, has developed a style of urbanization that not only amplifies natural hazards but reactivates dormant hazards and creates hazards where none existed.

Wesley Marx, Acts of God, Acts of Man (1977)

What was exceptional was not the storm itself (a 20-year event, according to meteorologists), but the way in which it was instantly assimilated to other recent disasters as a malevolent omen. As a Los Angeles Times columnist put it, Theres no question that [we are] caught in the middle of something strange maybe God, as the biblical sorts preach, is mad at us for making all those dirty movies.

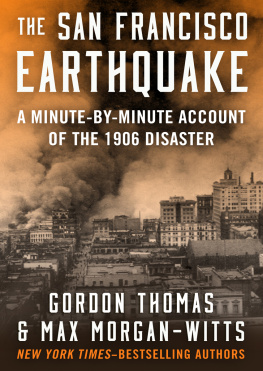

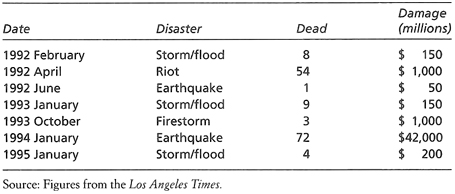

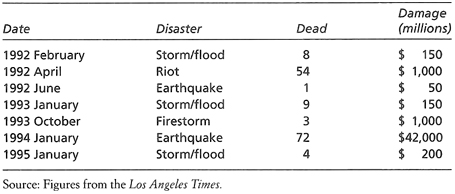

The destructive February 1992, January 1993, and January 1995 floods ($500 million in damage) were mere brackets around the April 1992 insurrection ($1 billion), the OctoberNovember 1993 firestorms ($1 billion), and the January 1994 earthquake ($42 billion). When damage accounting was finally completed in 1997, the Northridge earthquake emerged as the costliest natural disaster in American history, more destructive, according to a Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) spokesperson, than the combined impacts of the Midwest floods, Hurricane Andrew, the Loma Prieta earthquake and South Carolinas Hurricane Hugo.

From Ventura to Laguna, nearly two million Southern Californians were directly touched by disaster-related death, injury, or damage to their homes and businesses. The Northridge earthquake alone, according to the California Seismic Safety Commission, affected the lives of more people than any previous natural disaster in the United States.

For some unlucky souls, disaster has been a relentless, Job-like ordeal. Los Angeles firefighter Scott Miller, for example, was shot in the face during the 1992 riots while riding in his fire truck. He spent months in the hospital and was dismissed from the fire department due to disability. Two years later, his Granada Hills home was wrecked in the Northridge earthquake. Then, in early 1996, his new four-bedroom home in the Ventura County suburb of Newberry Park was destroyed by fire.

This virtually biblical conjugation of disaster, which coincided with the worst regional recession in 50 years, is unique in American history, and it has purchased thousands of one-way tickets to Seattle, Portland, and Santa Fe. After a century of population influx, 529,000 residents, mostly middle-class, fled the Los Angeles metropolitan region in the years 1993 and 1994 alone. Partly as a result of this exodus, the median household income in Los Angeles County fell by an astonishing 20 percent (from $36,000 to $29,000) between 1989 and 1995. Middle-class apprehensions about the angry, abandoned underclasses are now only exceeded by anxieties about blind thrust faults and hundred-year floods. Meanwhile, Caltech seismologists warn that the Pacific Rim is only beginning its long overdue rock and roll: the Kobe catastrophe may be a 3-D preview of Los Angeles 2000. And waiting in the wings are the plague squirrels and killer bees.

BIBLICAL DISASTERS?

It is still unclear, moreover, whether this vicious circle of disaster is coincidental or eschatological. Could this be merely what statisticians wave away as the Joseph effect of fractal geometry: the common clustering of catastrophe? Could these be the Last Days, as prefigured so often in the genre of Los Angeles disaster fiction and film (from Day of the Locust to Volcano )? Or is nature in Southern California simply waking up after a long nap? Whatever the case, millions of Angelenos have become genuinely terrified of their environment.

The $42 billion earthquake

Paranoia about nature, of course, distracts attention from the obvious fact that Los Angeles has deliberately put itself in harms way. For generations, market-driven urbanization has transgressed environmental common sense. Historic wildfire corridors have been turned into view-lot suburbs, wetland liquefaction zones into marinas, and floodplains into industrial districts and housing tracts. Monolithic public works have been substituted for regional planning and a responsible land ethic. As a result, Southern California has reaped flood, fire, and earthquake tragedies that were as avoidable, as unnatural, as the beating of Rodney King and the ensuing explosion in the streets. In failing to conserve natural ecosystems it has also squandered much of its charm and beauty.

But the social construction of natural disaster is largely hidden from view by a way of thinking that simultaneously imposes false expectations on the environment and then explains the inevitable disappointments as proof of a malign and hostile nature. Pseudoscience, in the service of rampant greed, has warped perceptions of the regional landscape. Southern California, in the most profound sense, is suffering a crisis of identity.

2. DEEP MEDITERRANEANEITY

This is a landscape of desire. More than in almost any other major population concentration, people came to [Southern California] to consume the environment rather than to produce from it.