This edition published in Australia in 2013 by Pier 9, an imprint of Allen & Unwin

First published in 1971 by Jacaranda Press.

Copyright Hugh Anderson 1971, 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body than administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Murdoch Books Australia

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

www.murdochbooks.com.au

info.murdochbooks.com.au

Murdoch Books UK

Erico House, 6th Floor

93-99 Upper Richmond Road

Putney, London SW15 2TG

Phone: (44 0) 20 8785 5995

Fax: (44 0) 20 8785 5985

www.murdochbooks.co.uk

info.murdochbooks.co.uk

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN: 9781 74336 505 2

eISBN: 9781 74343 475 8

Contents

PREFACE

I n the early years of black and white television in Melbourne, over forty years ago, we watched many crime files, including The Untouchables , set in the 1920s and 30s. I remember asking with a nationalistic fervour: if we want crooks, why not Australian ones?

Then I found an entry under the heading Crimes, Notable in the Australian Encyclopedia and went through the names until I came to the heading Taylor, Murray, Buckley (191531). I could find no book-length treatment of the threesome, and so I decided to embark on one of my own.

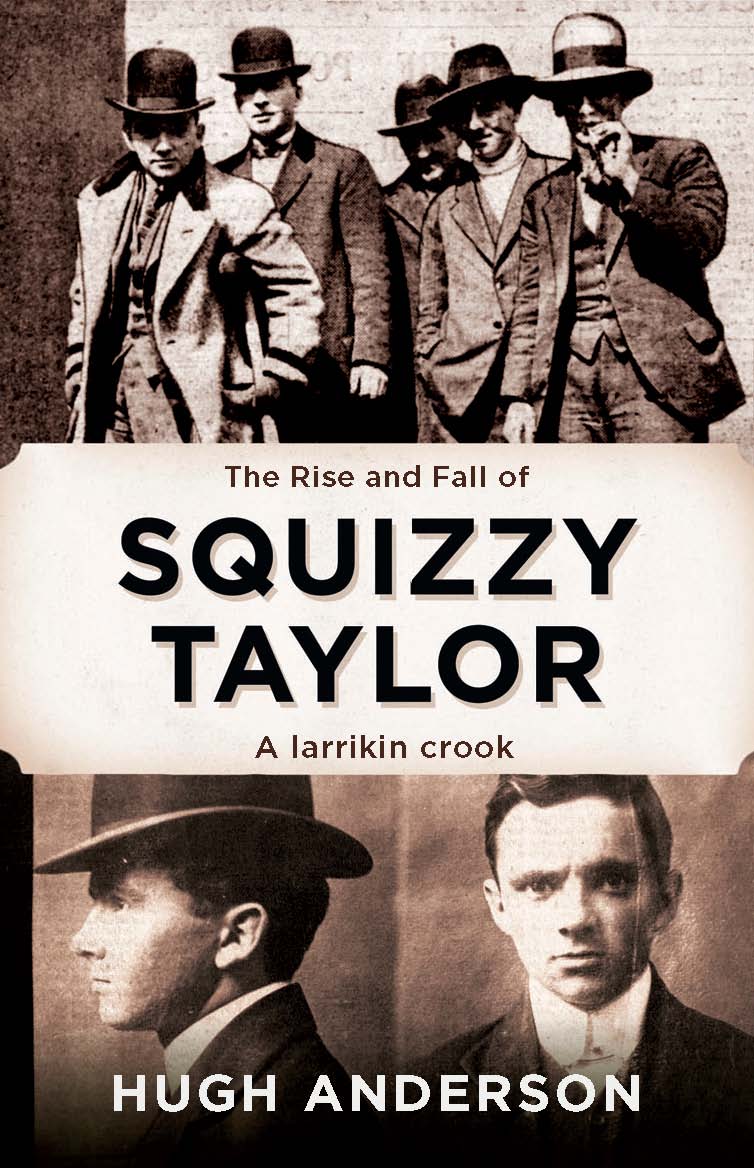

The reference text began: For more than a decade during and following World War 1 the names of Leslie (Squizzy) Taylor, Angus Murray (christened Henry James Donnelly) and Richard Buckley were linked in one of Australias most notorious associations of crime. Taylor was a diminutive but vicious and shrewd criminal who dominated the underworld of Melbourne, Murray, a vain but intelligent young man who had gone wrong and Buckley, wrongly flogged as a youth, was a man who made war on society and received sentences said to total seventy-one years.

I began a search for material to fill out their criminal lives. At first, I thought the book should have the realism of a Dos Passos novel, with each chapter opening with a piece of social, political or economic comment culled from contemporary newspaper articles, but in the end I was unable to sustain the method, for various reasons. I was already a published writer of historical books, but I did not think to check for living sources until long afterwards. I wanted written evidence, and depended entirely on printed documents.

One afternoon in the public library, I met a young (that is much younger than I) filmmaker, Nigel Buesst, who told me he was intent on making a biopic or documentary dealing with Squizzy Taylor. He had been stimulated, he said, by the film on Bonny and Clyde. Nigel subsequently came to our house and did an interview on camera and provided some illustrations for my then unpublished book. His film was shown on television one night (about 1970), and the following morning I received several telephone calls from publishers, including Chas Conlon at the Melbourne office of Jacaranda Press, who immediately offered a contract (and was henceforth known in the industry as Squizzy Conlon).

In 1971, when Jacaranda issued the book, Conlon decided the launch would be held in a hotel at the Paris end of Gertrude Street, Fitzroy, a supposed haunt of Taylor. However, owing to a dispute, the shipment of books was on hold at the Brisbane wharfs, and we only had about six copies on hand. Chas said we would just get on with the free drinks and dispense with any speeches, but as gloom settled on the affair I foolishly thought that I should make a speech, and stood on a chair in the back parlour.

Louts, touts and bashers, I began in Shakespearean manner, fully misjudging the scene. Lend me your ears. I come to praise Taylor, not to bury him.

The effect was immediate on some of the locals who were enjoying the free pots of beer and one tried to pull me from my precarious platform, mumbling something about burying the dead. Members of the audience came to life and the press reporters began milling about, while the publican reached under the bar where he kept a shillelagh to enforce order. A large friend, a criminologist at the University of Melbourne, stepped forward (on my toes) and pushed him away.

For the next day or so I was a newspaper hero with a few pars about an author attacked at a book launch and was briefly in demand for radio interviews, but it was weeks before copies were generally available in Melbourne. By then most interest had evaporated.

The rest, we might say, is history.

Hugh Anderson

Australian Centre, University of Melbourne

2011

INTRODUCTION

A n acute observer of life in colonial Australia as early as the 1820s considered some young men took to robbery and the bush from the vanity of being talked of. Squizzy Taylor, so well-known a century later, was also vain and wilful, and his greatest attraction to the class in which he reigned lay in his vital, audacious approach to crime. As with the bushrangers, he gained esteem and some sympathy beyond the criminal strata because he caused, comparatively, so little bloodshed, because he seemed to act with freedom, to be master of his fate, and his activities to be propelled by an adventurous spirit. In this way, he dramatised for many the seeming futility of the daily suburban round and became to the middle class a psychic substitute for violence.

Im only a newspaper hero, Taylor once told a court with a rare touch of truth, and there was in the daily press reports of his crimes a novel halo for this cunning little crook who continually outwitted the police. In the dock he smiled sneeringly whenever his counsel asked a question or made a derogatory observation to those responsible for his plight. When the jurys verdict was Not Guilty, he favoured the traditional enemy, the prosecuting police, with a triumphant, mocking smile.

He was happy to co-operate with journalists who wrote favourably of him, and to some small degree, Squizzy rose from a blustering young larrikin at the turn of the century to notoriety as a gangland leader on the basis of lionising newspaper articles. Yet, in retrospect, Leslie Taylor was no daredevil mastermind. From the time his imagination was fired to promote a rival gang and overthrow the little New York Jew, Lou (The Count) Stirling, and his henchmen, he made careful plans and saw that they were thoroughly carried out, but always with the chief regard to his personal safety.

The bushrangers of Australia occupy a prominent place in the national ethos; to many they were, and still remain, heroic symbols of resistance to constituted authority colourful figures with the added prestige of being professional opponents of the police. The qualities befitting a bushranger were independence, adaptability and resourcefulness; qualities their sympathisers felt they also possessed. It was as if the bushrangers were regarded simply as themselves writ large: there but for the whims of fortune go I.

This is the romantic viewpoint, with Squizzy Taylor the city equivalent of the ranger of the bushBen Hall in modern dressand Buckleys mingling of despair and defiance after receiving the lash is transmitted as the recalcitrant spirit of some convict bolter. Even today, some characters are described in grudging admiration as bushrangers, and every Australian child has heard of the gameness of Ned Kelly.