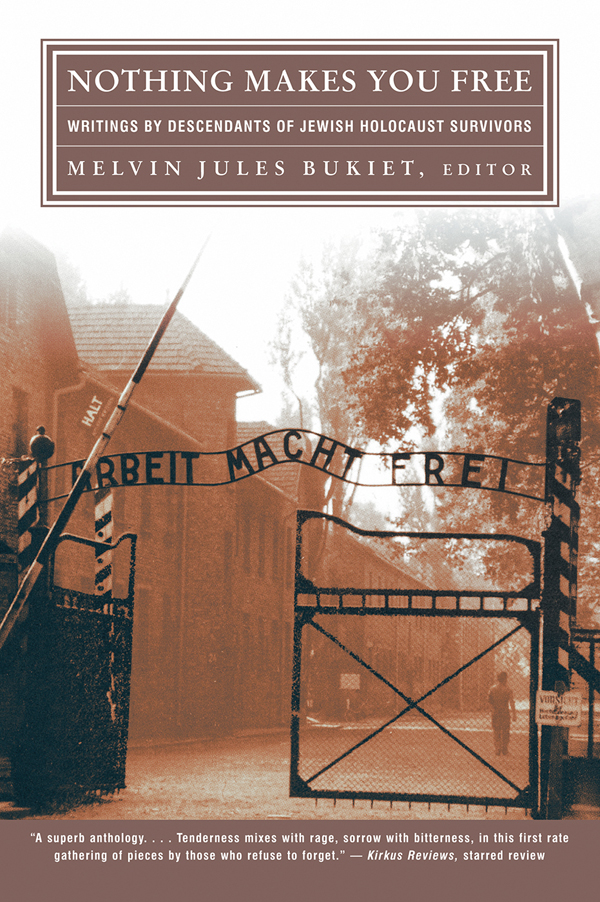

Nothing

Makes

You

Free

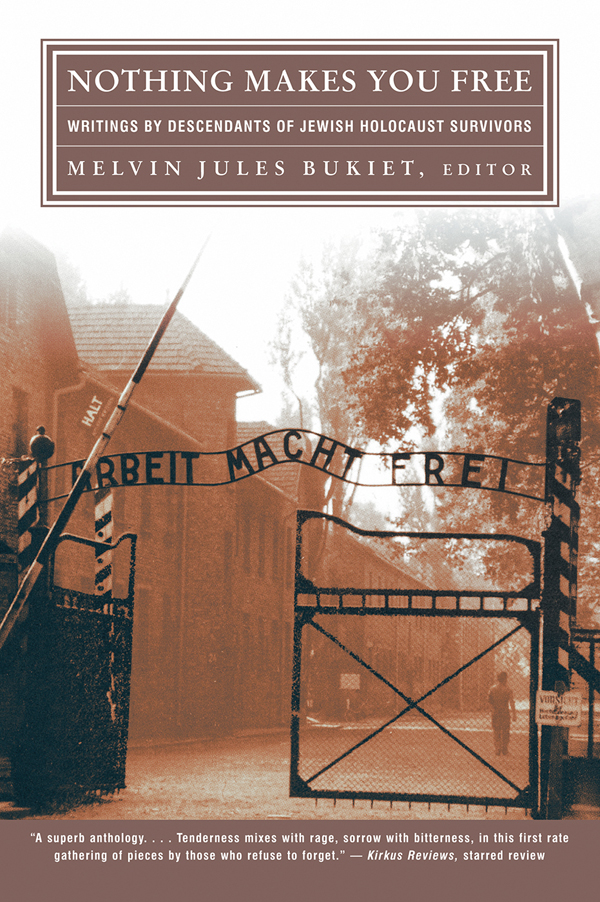

Writings by Descendants of Jewish Holocaust Survivors

Edited by Melvin Jules Bukiet

To: Madelaine, Louisa, and Miles,

also known as Mindel, Chaya Leah, and Meier

Contents

A rock drops into the center of a pond. Ripples spread. Make that a flaming comet crashing into a boiling tar pit. A tidal wave ensues. Consider the Holocaust as that first event. Call the pit Europe.

The Jews, poor schnooks, believed that Europe was a temporary residence they occupied while awaiting return to the true Holy Land. Until that day of redemption arrived, however, they lived quietly: working, studying, making sure their chickens were kosher. Most engaged in daily worship to the God who drove them from Zion into Babylonia, Rome, Spain, medieval Mittel-Europa and, finally, the fertile Polish countryside. Even the few city sophisticates who read and wrote for newspapers breathed exile. So occasionally a drunken peasant cudgeled a Jewish tot, who died. So there were blood libels. Pogroms. What did you expect? This was Eastern Europe wheredespite Marx, Rothschild, and Freud; Kafka, Chagall, and Schoenbergnot much had changed since the Middle Ages. Life was precarious, yet it went on as it had in ages past. How could these people dream that here, in their own time, centuries of fruitfulness and multiplication would come to nothing?

A friend of my family grew up in Oswiecim, a village thirty miles west of Cracow which, due to the German tongues inability to pronounce the Slavic syllables, came to be known as Auschwitz. He played there with the other children amidst the groves of birch trees where a world of Jews would utter their last prayers before a bullet... before a knife... before a brick... before a doctor, a butcher, a baker... before the gas.

Then came D-Day, the Red Army, German surrender. Concentration camps were liberated, and approximately one hundred thousand Jews were released from Hell. Many more emerged from years of hiding in terror.

What a strange world they inhabited. Their homes were burnt, their culture destroyed, their God silent. It was a world without very young or very old people, because most of those who survived were between twenty and thirty and had been deemed fit for work, temporarily. Perhaps most bizarrely, the survivors was a world without parents, a world of orphans.

Like their literal mothers, their mameloshen, Yiddish, was now as dead as Sanskrit. That was appropriate, because the survivors were ghosts floating across the devastated landscape. Much congratulatory celebration is made these days of their vigor, their character, and their mere existence, but lets keep one terrible truth on the table. In fact, Hitler won. The Jews lost, badly. The continent is morally, culturally, essentially Judenrein. Thus, the survivors were expected to remain unobtrusive supernatural phenomena, not disturbing the living with the clanking of their chains and their alarming stories. In return, a guilty world tried to salvage its conscience by granting passports to the United States and other nations to those whose entry they barred a decade earlier.

For the most part, the survivors obliged. They pretended to live normal lives, to find work, pay rent, eat dinner. A few like Elie Wiesel and Primo Levi chronicled their individual and communal catastrophe in print, but most lived as privately abroad as they had in their destroyed homes. This was the 1950s and the Holocaust had not entered the public consciousness as it would thirty years later. But the survivors could not wait to be discovered, so the tailor in Borough Park, the builder in New Jersey, the housewife in Miami, and their co-equals in Tel Aviv and London and Melbourne told their stories to each other over games of gin. They also told them to the only others who had no choice but to listen: their children.

Despite every possible attempt to obliterate them from the face of the earth, these phantoms had returned to the land of the living, and that meant meeting and mating and bearing squawling infants who wouldnt have stood a chance one single decade earlier. Whether they remained in Europe as eighteenth-generation Germans or were born in the United States as first-generation Americans, within Holocaust circles the children are known as the Second Generation.

In a way, life has been even strangerthough infinitely less perilousfor the chidren than the parents. If a chasm opened in the lives of the First Generation, they could nonetheless sigh on the far side and recall the life Before, but for the Second Generation there is no Before. In the beginning was Auschwitz. On the most literal level, their fathers would not have met their mothers if not for the huge dislocations that thrust the few remnants of European Jewry into contact with spouses they would never have otherwise encountered except for DP camps or in the twentieth-century Diaspora. The Second Generations very existence is dependent on the whirlwind their parents barely escaped.

No one who hasnt grown up in such a household can conceive it, while every 2G has something in common. Every one of these happy or unhappy families knows a variation of the same unhappy story. Of course, some survivors spoke incessantly of the Holocaust while others never mentioned it. Of those who didnt speak, some were traumatized while others hoped to protect their offspring from knowledge of the tree of evil.

The Second Generation will never know what the First Generation does in its bones, but what the Second Generation knows better than anyone else is the First Generation. Other kids parents didnt have numbers on their arms. Other kids parents didnt talk about massacres as easily as baseball. Other kids parents had parents.

Other kids parents loved them, but never gazed at their offspring as miracles in the flesh. Most of us werent born in mangers, but we might as well have been. Other kids werent considered a retroactive victory over tyranny and genocide.

So what do you do with this cosmic responsibility? You were born in the fifties so you smoked dope and screwed around like everyone else. But your rebellion was pretty halfhearted, because how could you rebel against these people who endured such loss? Compared to them, what did you have to complain about?

How do you deal with it? As adults, many 2Gs took up the helping occupations and became shrinks or social workers while others became involved with Jewish charities. And if you were a writer, you wrote.

Lord knows, you werent alone, because along with your personal maturity the Holocaust has ripened, and the floodgates to exploration of this awful era opened. Why it didnt happen immediately after the war, I dont know. Understandably, people didnt want to think about it, but a delayed-action fuse eventually ignites and we are witnessing the explosion right now.

The comet hits at six million miles per hour and the waves spread. From the primary sources of the First Generation to the Second Generation it has swelled to include other Jews (Saul Bellows Mr. Sammlers Planet, Cynthia Ozicks The Shawl ) and then non-Jews (John Herseys The Wall and William Styrons putative Holocaust book, Sophies Choice, followed by Pat Conroys Beach Music and Carribean writer Caryl Phillipss The Nature of Blood ). Over the last few years, Ive noticed that virtually every book Ive readan Australian novel about a millennial cult in the outback, a Brazilian novel about gangsters and gem dealers, a gay cross-dressing fantasia, a noirish portrayal of the movie business, a semi-memoir of a young black poet in an L.A. slumto greater or lesser extent involve the Holocaust. Some are good books, some are bad, but thats not the point. Whats important is that the Holocaust has become a talismanic touchstone that every writer must genuflect toward. Try an experiment. Take every tenth book of fiction off the shelves of your local bookstore. A few will actually be about the Holocaust, but count how many others mention, just mention, in passing, as a metaphor, the H word as a kind of seal of literary seriousness. My guess is seven out of ten.

Next page