Table of Contents

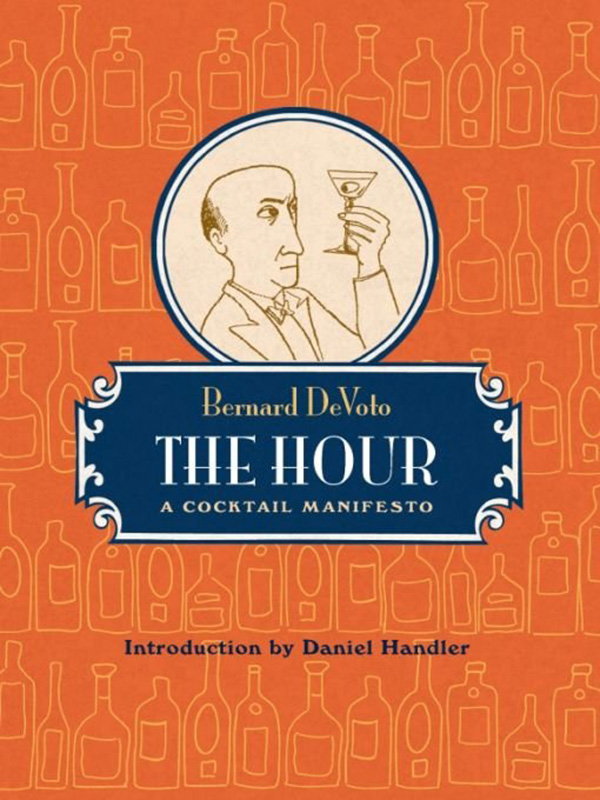

BOOKS BY BERNARD DEVOTO

THE CROOKED MILE

THE CHARIOT OF FIRE

THE HOUSE OF SUN-GOES-DOWN

MARK TWAINS AMERICA

WE ACCEPT WITH PLEASURE

FORAYS AND REBUTTALS

MINORITY REPORT

MARK TWAIN AT WORK

THE YEAR OF DECISION

THE LITERARY FALLACY

MOUNTAIN TIME

ACROSS THE WIDE MISSOURI

THE WORLD OF FICTION

THE HOUR

Introduction

BY DANIEL HANDLER

FOR A SHORT TIME IN MY CHILDHOOD I THOUGHT MY father, a certified public accountant, was a bootlegger. Part of this was brought about by an overactive imagination, fed by too much Carson McCullers at a tender age, resulting in my confusing of the terms moonshining and moonlighting. (Imagine my anticipation, and then my disappointment, when I heard that Bruce Willis and Cybil Shepard were going to be in a television show about illegal distillation.) But the real reason for my suspicions is that my father, once or twice a year, could be found in the basement fiddling with bottles and funnels. It turned out that he was making half and half that is, sweet and dry vermouth in equal parts, a mixture that my father was no longer able to find commercially and which was a crucial ingredient in the Perfect Manhattan he enjoyed everyday after work. When I asked him why he didnt take an extra second and add both vermouths to each cocktail, rather than puttering at length in dim light over a filthy sink, he gave me a curious look. To save time, he explained.

A generation later my son had his first martini. He was eighteen months old and it was six oclock. He had watched me mix my own drink, and indicated with a series of hand gestures and bleats his curiosity to try it. I gave him a sip, and his baby blues watered over. He cried for a few seconds, and then, stretching his arms out, uttered through his tears one of the few words he knew: More.

This is an absurdly complicated world. We so often want what will only bring us more grief, and our moral and logistical strategies rarely make a whit of sense when we open the basement doors. Since time immemorial, when bitchslapped by this bitter epiphany, we have reached for strong drinkonly to find that it is an exemplar of our contradictory ways rather than an antidote for them. Drinking, like existence, is an endless muddle, one of the slipperiest boulders in lifes daunting streamwe cling to it for support but end up even wetter than when we started. It destroys individuals and rescues large gatherings. It can tear apart loved ones but bring strangers closer together. It starts fights and ends wars. One drinks a right and proper amount; everyone else drinks either too much or not enough. Ones own drinking preferences exhibit refinement and sophistication; everyone elses are suspect, as are everyone elses snobberies, recipes, rules, brands, and styles. Alcohol starts endless debates, and endless debates are best settled over a drink.

Such a state of affairs cries out for clarity, and Bernard DeVotos splendid book The Hour provides it straight up. DeVoto is as clear as gin. There have been other books that have suggested ways to transform the world, along with precise instructions on how to carry out this transformationthe New Testament springs to mindbut few have managed to simultaneously convey the likelihood that any solution to the absurdity of life is likely, also, to be absurd. There are some aspects of The Hour that have not aged welldespite DeVotos decrying, early on, of male egotism, this book is unlikely to be regarded nowadays as a paragon of gender equalitybut the books unwavering nobility has not dimmed any more than the unwavering nobility of its quest. For us to drink more. Of certain drinks. At six oclock. But not too much.

Bernard DeVotos name may not ring a bell now, but people were certainly listening in his time. DeVoto was an historian and a journalist, a scholar and a polemicist, a novelist and a soldier. He curated the papers of Mark Twain and edited the journals of Lewis and Clark. He wrote a column for twenty years at Harpers Magazine, incurring the ire of the FBI and the state of Utah. He won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award, and his immense, three-volume history of the American West is still in print and still read, although less in living rooms than in American Studies departments, not so much as history but as a product of its time. DeVotos work has undergone the common but curious transformation from the canonical to the unfashionable, but if his fame has dimmed, it does not appear to be because he did not do enough but perhaps because he did so much; erudite but distrustful of academia, populist but not pandering, serious but not difficult, his work crosses so many boundaries that nobody knows where to hoist his flag.

In DeVotos biography, written by none other than Wallace Stegner, The Hour is described both as a piece of humorous cultural patriotism and a manual of witchcraft, but thats about all one can find of this little book in the dusty critical studies and largely neglected Web sites dedicated to DeVotos career. But The Hour has been kept alive by a different subculturethat of the cocktail enthusiast. I found the book in the window of a bookstore surrounded by vintage cocktail recipe compendiumsof which I have a modest collectionoffering drink concoctions that are fun to read but grotesque to sample, as far too many guests to my home can attest.

DeVoto is likely sputtering in his grave at such company. There are only two cocktails, The Hour proclaims. The bar manuals and the womens pages of the daily press, I know, print scores of messes to which they give that honorable and glorious name. They are not cocktails, they are slops. He calls instead for either a slug of whiskeymy fathers drink, the Manhattan, is an offense against pietyor the martini, a mixture of gin and vermouth (the word vodka is not to be found in the book) and nothing else, not even an olive. ([N]othing can be done with people who put olives in martinis, presumably because in some desolate childhood hour someone refused them a dill pickle and so they go through life lusting for the taste of brine.)

The book continues in this stern, decisive tone, instructing the innocents on everything from alternate ingredients of the martini (Orange bitters make a good astringent for the face. Never put them in anything that is to be drunk.) to instructions on what to hum while preparing them ([I]t should be nostalgic but not sentimental, neither barbershop nor jazz, between the choir and the glee club.) But The Hour is really after a truth less exacting: that there is a sacredness to the time when the workday ends and the evening begins that ought to be observed with a civilized ritual. Though the books tone might be described as deadpan fascism, the text offers a freedom of mind and spirit.

Before Tin House made getting The Hour much easier, I used to search regularly for copies of this book to give to friends. Once, I called a bookstore some two thousand miles from my home and inquired about their Internet listing.

Oh yes, the bookseller replied, after shed gone to check. We have two copies, actually. Which one do you want?

Both of them, I said.

Actually, she said, theres only one available. Im going to buy the other one.

I swear I could hear the glint in her eye. It was the look my father had when he was caught in his elaborate time-saving ritual, and the look my son gave me when he reached for the comfort that made him cry. It was the desire for clarity, in the form of muddle; stability, in the form of intoxication. It is the look I see now in the mirror, with my essay done and the sun setting. It is a desire for