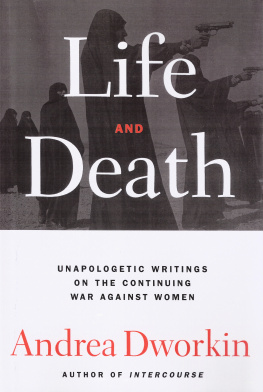

Dworkin - Life and death : [unapologetic writings on the continuing war against women]

Here you can read online Dworkin - Life and death : [unapologetic writings on the continuing war against women] full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New York etc, year: 1997, publisher: Free Press, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Life and death : [unapologetic writings on the continuing war against women]

- Author:

- Publisher:Free Press

- Genre:

- Year:1997

- City:New York etc

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Life and death : [unapologetic writings on the continuing war against women]: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Life and death : [unapologetic writings on the continuing war against women]" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Dworkin: author's other books

Who wrote Life and death : [unapologetic writings on the continuing war against women]? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Life and death : [unapologetic writings on the continuing war against women] — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Life and death : [unapologetic writings on the continuing war against women]" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

REMEMBER, RESIST, DO NOT COMPLY

I want us to think about how far we have come politically. I would say we have accomplished what is euphemistically called breaking the silence. We have begun to speak about events, experiences, realities, truths not spoken about before; especially experiences that have happened to women and been hiddenexperiences that the society has not named, that the politicians have not recognized; experiences that the law has not addressed from the point of view of those who have been hurt. But sometimes when we talk about breaking the silence, people conceptualize the silence as being superficial, as if there is talkchatter, reallyand laid over the talk there is a superficial level of silence that has to do with manners or politeness. Women are indeed taught to be seen and not heard. But I am talking about a deep silence: a silence that goes to the heart of tyranny, its nature. There is a tyranny that preordains not only who can say what but what women especially can say. There is a tyranny that determines who cannot say anything, a tyranny in which people are kept from being able to say the most important things about what life is like for them. That is the kind of tyranny I mean.

The political systems that we live in are based on this deep silence. They are based on what we have not said. In particular, they are built on what womenwomen in every racial group, in every class, including the most privilegedhave not said. The assumptions underlying our political systems are also based on what women have not said. Our ideas of democracy and equalityideas that men have had, ideas that express what men think democracy and equality areevolved absent the voices, the experiences, the lives, the realities of women. The principles of freedom that we hear enunciated as truisms are principles that were arrived at despite this deep silence: without our participation. We are all supposed to share and take for granted the commonplace ideas of social and civic fairness; but these commonplace ideas are based on our silence. What passes as normal in life is based on this same silence. Gender itselfwhat men are, what women areis based on the forced silence of women; and beliefs about communitywhat a community is, what a community should beare based on this silence. Societies have been organized to maintain the silence of womenwhich suggests that we cannot break this deep silence without changing the ways in which societies are organized.

We have made beginnings at breaking the deep silence. We have named force as such when it is used against us, although it once was called something else. It used to be a legal right, for instance, that men had in marriage. They could force their wives to have intercourse and it was not called force or rape; it was called desire or love. We have challenged the old ideology of sexual conquest as a natural game in which women are targets and men are conquering heroes; and we have said that the model itself is predatory and that those who act out its aggressive imperatives are predators, not lovers. We have said that. We have identified rape; we have identified incest; we have identified battery; we have identified prostitution; we have identified pornographyas crimes against women, as means of exploiting women, as ways of hurting women that are systematic and supported by the practices of the societies in which we live. We have identified sexual exploitation as abuse. We have identified objectification and turning women into commodities for sale as dehumanizing, deeply dehumanizing. We have identified objectification and sexual exploitation as mechanisms for creating inferiority, real inferiority: not an abstract concept but a life lived as an inferior person in a civil society. We have identified patterns of violence that take place in intimate relationships. We know now that most rape is not committed by the dangerous and predatory stranger but by the dangerous and predatory boyfriend, lover, friend, husband, neighbor, the man we are closest to, not the man who is farthest away.

And we have learned more about the stranger, too. We have learned more about the ways in which men who do not know us target us and hunt us down. We have refused to accept the presumption in this society that the victim is responsible for her own abuse. We have refused to agree that she provoked it, that she wanted it, that she liked it. These are the basic dogmas of pornography, which we have rejected. In rejecting pornography we have rejected the fundamentalism of male supremacy, which simply and unapologetically defines women as creatures, lower than human, who want to be hurt and injured and raped. We have changed laws so that, for instance, rape now can be prosecuted without the requirement of corroborationthere does not have to have been an eyewitness who saw the rape before a woman can press charges. There used to have to be one. A woman now does not have to fight nearly to the death in order to show that she resisted. If she was not sadistically injuredbeaten black and blue, hit by a lead pipe, whateverthe presumption used to be that she consented. We have standardized the way in which evidence is collected in rape cases so that whether or not a prosecution can be brought does not depend on the whims or competence of investigating officers. We have not done any of this for battered women, though we have tried to provide some refuge, some shelter, an escape route. Nothing that we have done for women who have been raped or battered has helped women who have been prostituted.

We have changed social and legal recognition of who the perpetrator is. We have done that. We have challenged what appears to be the permanence of male dominance by destabilizing it, by refusing to accept it as reality, our reality. We have said no. No, it is not our reality.

And although we have provided services for rape victims, for battered women, we have never been able to provide enough. I suggest to you that if any society took seriously what it means to have half of its population raped, battered as often as women are in both the United States and Canada, we would be turning government buildings into shelters. We would be opening our churches to women and saying, You own them. Live in them. Do what you want with them. We would be turning over our universities.

What remains to be done? To think about helping a rape victim is one thing; to think about ending rape is another. We need to end rape. We need to end incest. We need to end battery. We need to end prostitution and we need to end pornography. That means that we need to refuse to accept that these are natural phenomena that just happen because some guy is having a bad day.

In each country, male dominance is organized differently. In some countries, women have to deal with genital mutilation. In some countries, abortion is forced so that female fetuses are systematically aborted. In China, forced abortion is state-mandated. In India, a free-market economy forces masses of women to abort female fetuses and, failing that, to commit infanticide on female infants. Think about what policies on abortion mean for living, adult women: the meaning to their status. Notice that the Western concept of choicecrucial to usdoes not cover the situation of women in either China or India. Each time we look at the status of women in a given country, we have to look at the ways in which male dominance is organized. In the United States, for instance, we have the growth of a population of serial killers. They are a subculture in my country. They are no longer lonely deviants. Law enforcement sources, always conservative, estimate that each and every day nearly 400 serial killers are active in the United States.

In my view, we need to concentrate on the perpetrators of crimes against women instead of asking ourselves over and over and over again, why did that happen to her? what's wrong with her? why did he pick her? Why should he hit or hurt anyone: whats wrong with him? He is the question. He is the problem. It is his violence that we find ourselves running from and hiding from and suffering from. The womens movement has to be willing to name the perpetrator, to name the oppressor. The womens movement has to refuse to exile women who have on them the stench of sexual abuse, the smell, the stigma, the sign. We need to refuse to exile women who have been hurt more than once: raped many times; beaten many times; not nice, not respectable; dont have nice homes. There is no womens movement if it does not include the women who are being hurt and the women who have the least. The womens movement has to take on the family systems in our countries: systems in which children are raped and tortured. The womens movement has to take on the battered women who have not escapedand we have to ask ourselves why: not why didnt they escape, but why are we settling for the fact that they are still captives and prisoners.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Life and death : [unapologetic writings on the continuing war against women]»

Look at similar books to Life and death : [unapologetic writings on the continuing war against women]. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Life and death : [unapologetic writings on the continuing war against women] and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.

![Dworkin Life and death : [unapologetic writings on the continuing war against women]](/uploads/posts/book/97794/thumbs/dworkin-life-and-death-unapologetic-writings.jpg)