Thames & Hudson world of art

This famous series provides the widest available range of illustrated books on art in all its aspects.

To find out about all our publications, including other titles in the World of Art series, please visit www.thamesandhudson.com . There you can subscribe to our e-newsletter, browse or download our current catalogue, and buy any titles that are in print.

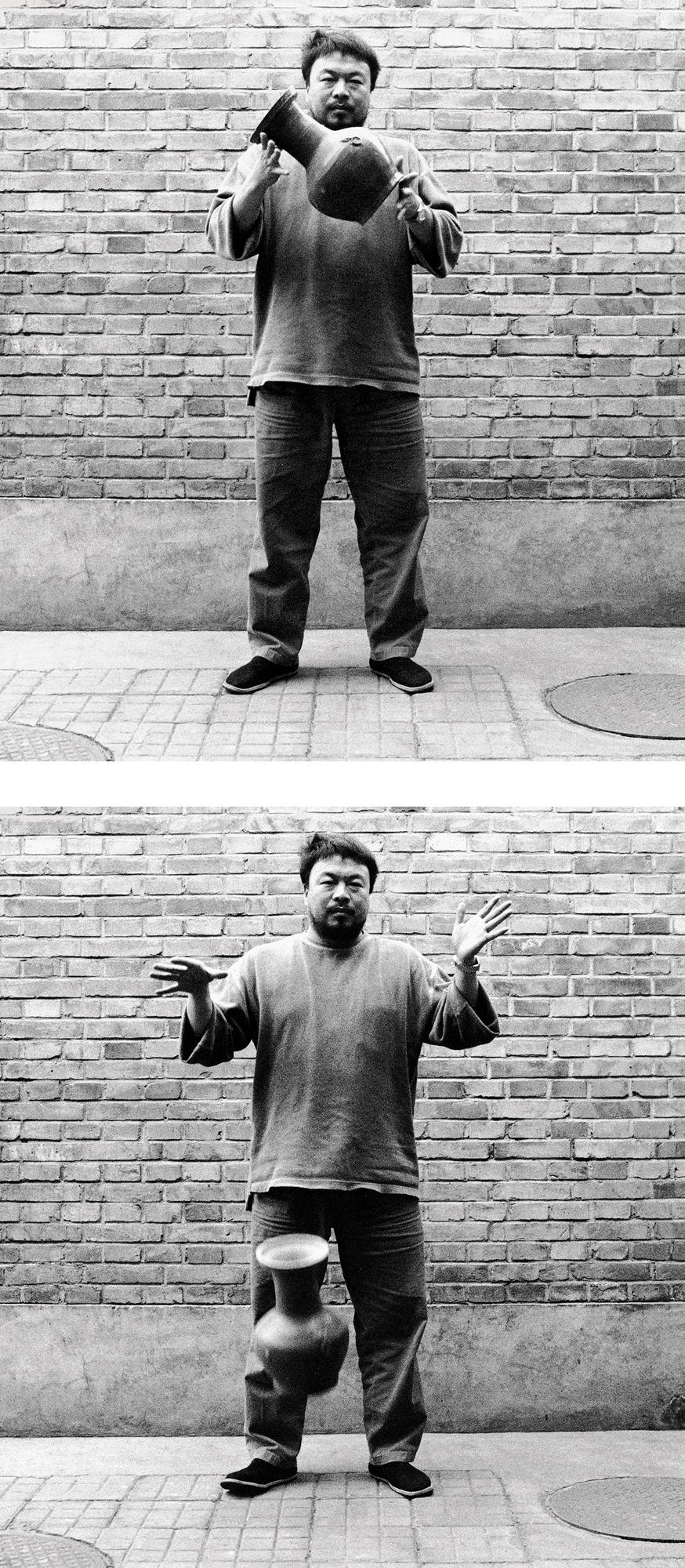

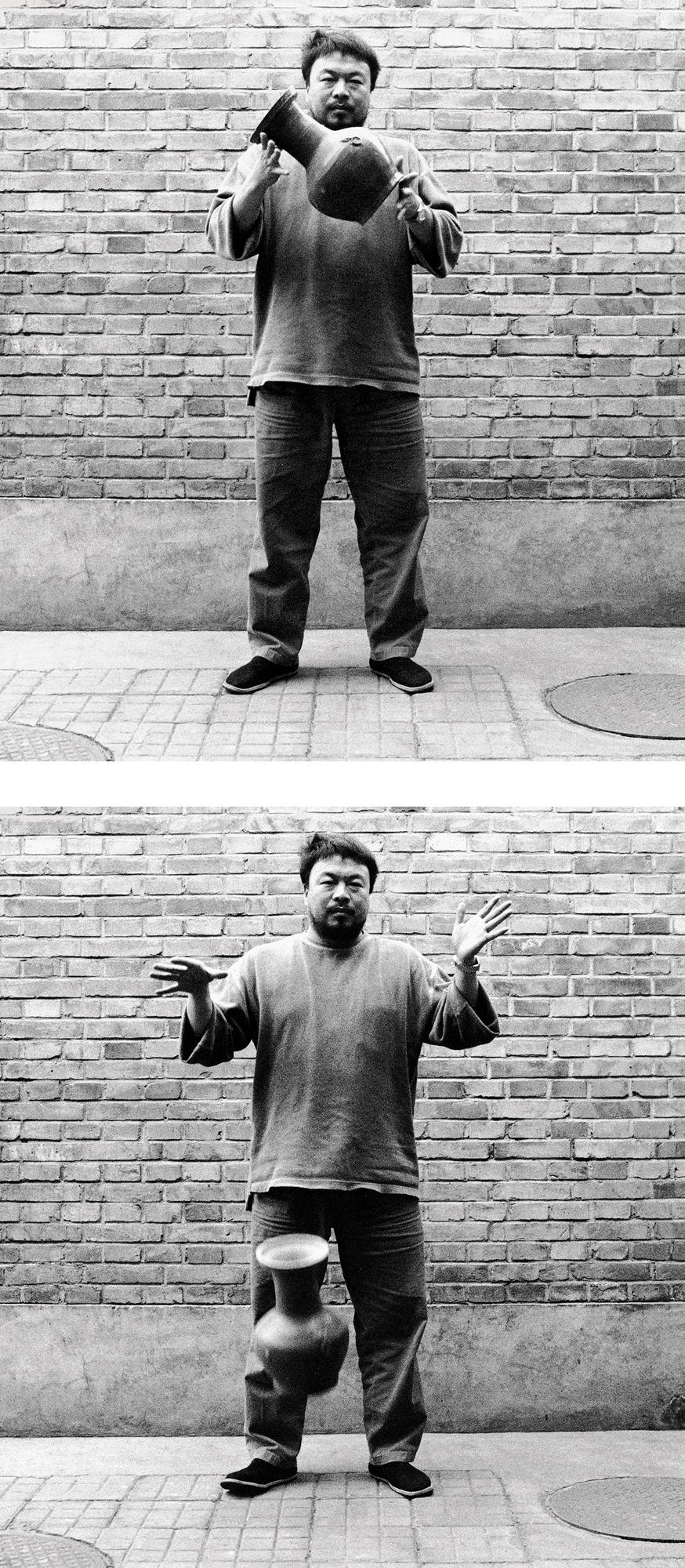

Ai Weiwei, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995. Three gelatin silver prints

Among the most famous works of the age, Ai Weiweis photographic triptych challenges observers to question the relationship between contemporary culture and traditional structures, art and authority, creation and destruction, the present and the past.

About the Author

Kelly Grovier is a poet, historian and cultural critic. He is a regular contributor on art to the Times Literary Supplement, and his writing has appeared in numerous publications, including the Observer, the Sunday Times and Wired. Educated at the University of California, Los Angeles and at the University of Oxford, he is co-founder of the international scholarly journal European Romantic Review and the author of 100 Works of Art that Will Define Our Age (published by Thames & Hudson).

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Digital Art

100 Works of Art That Will Define Our Age

Art Since 1900

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

For my brothers

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to my editors, Jacky Klein and Roger Thorp, for inviting me to tell this story. Thanks too are due to the team at Thames & Hudson (especially Allie Boalch, Sarah Hull, Aman Phull and Linda Schofield), without whose expertise, advice and care this book would not have been possible. I am also grateful to Anna Vaux, Alan Jenkins and Michael Caines at the Times Literary Supplement for the countless opportunities they give me to exercise my eyes and broaden my knowledge. For their kindnesses, conversations, and encouragement I would also like to express my gratitude to Mark Alexander, Tiffany Atkinson, Fred Burwick, Kate Burvill, Jean Fremon, Gavin Friday, Peter Green, Guggi, Darragh Hogan, Simon Hogg, Daniel Kennedy, John Kennedy, Justus Kewenig, Christopher Le Brun, Paddy McKillen, Eleanor Mills, Anthony Mosawi, Anna Mountford-Zimdars, Cornelia Parker, Sam Phillips, Jem Poster, Mark Robinson, Anne Stewart, Rosaleen Sturgeon, Jacqueline Thalmann, Tony Waddingham, Celia White and Ben Wright. I would also like to convey my gratitude to Sean, Liliane and Oisin for their generous hospitality. Finally, I would like to thank my parents for teaching me how to look at art, and, most especially, Sinad, who put up with me during the writing of this book and read every version of every sentence. She is entirely responsible for any errors.

Contents

1 Janine Antoni, Loving Care, 1992. Performance with Loving Care hair dye (Natural Black)

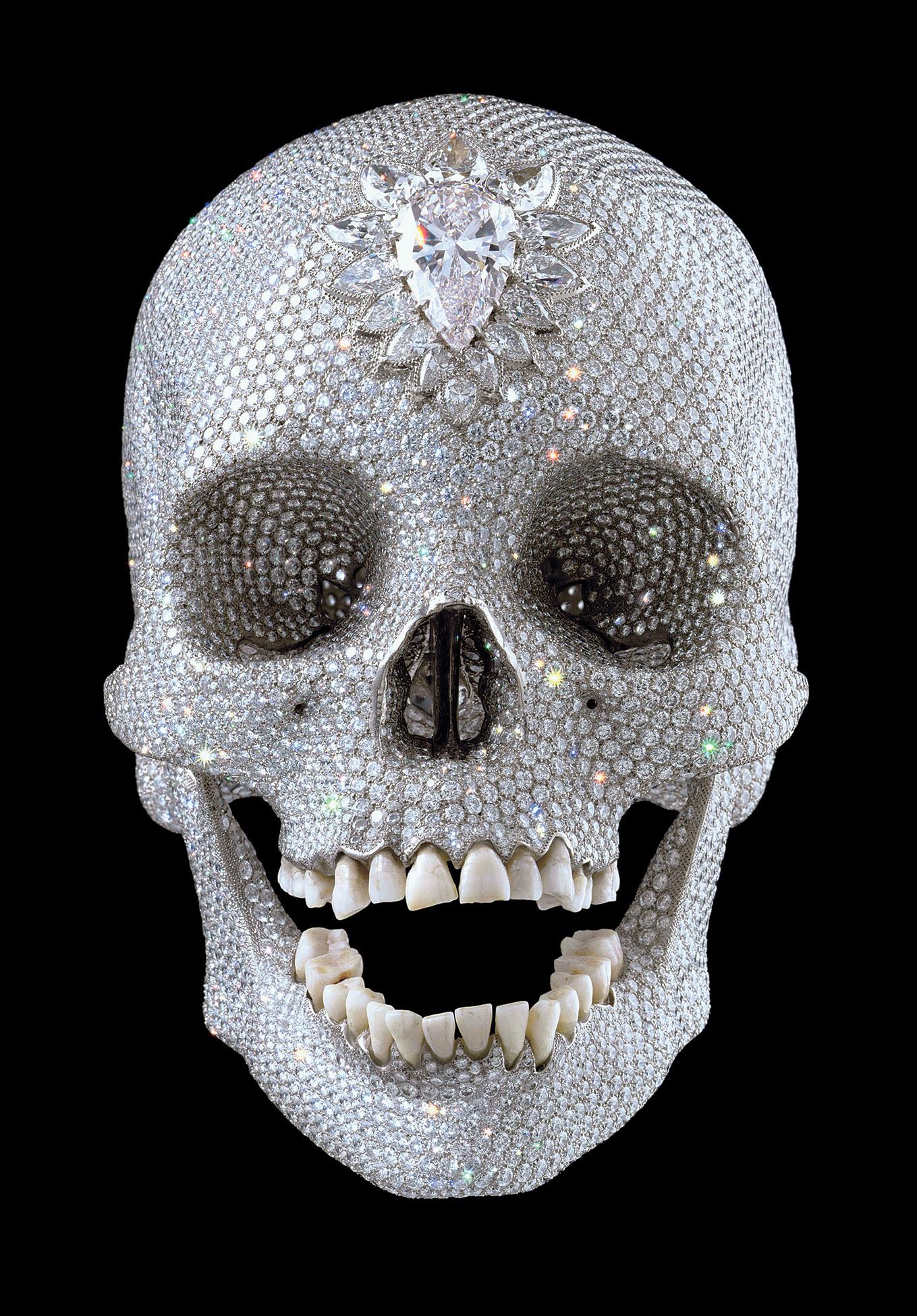

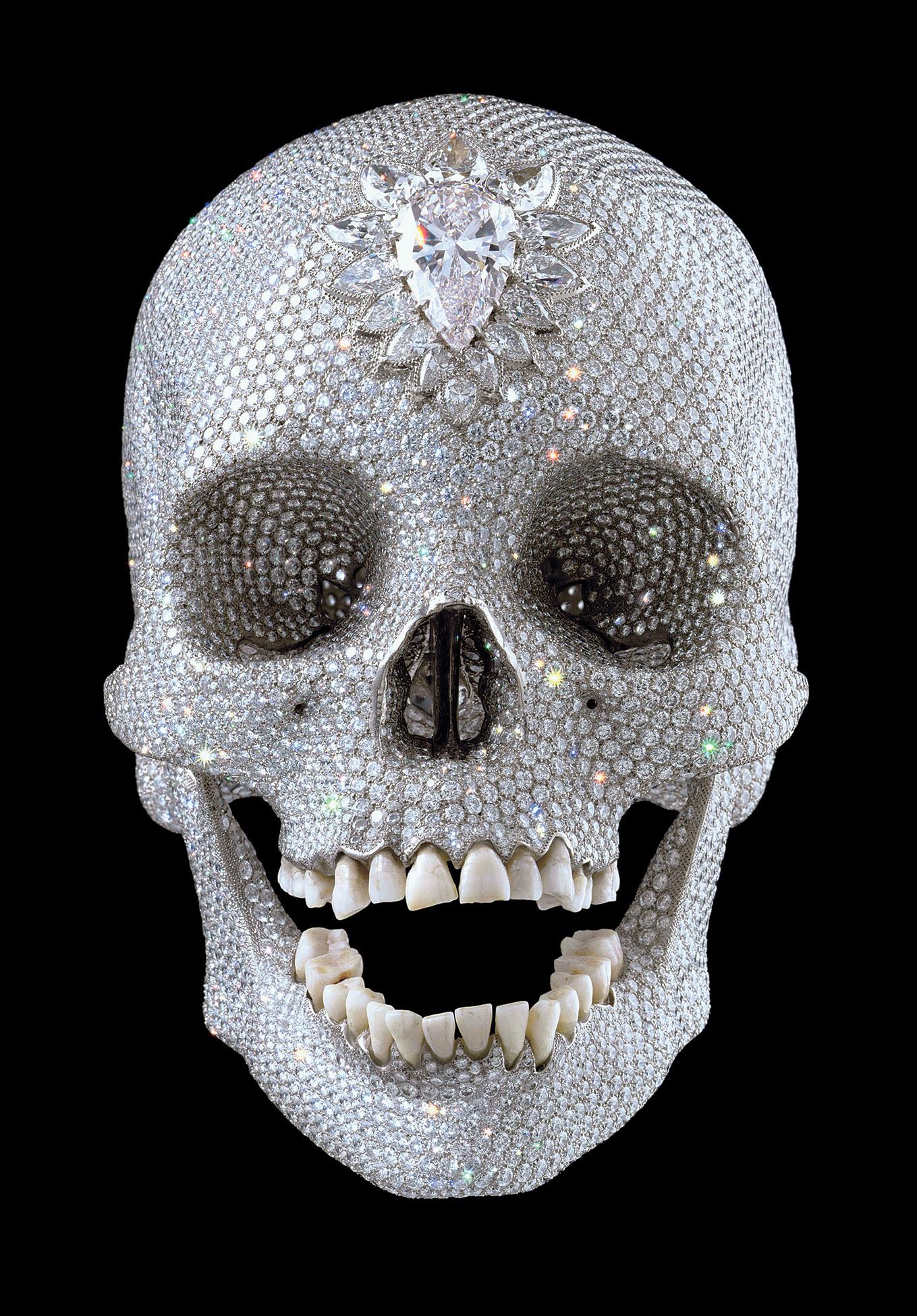

2 Damien Hirst, For the Love of God, 2007. Platinum, diamonds and human teeth

Imagine finding yourself in a maze of connected rooms. In front of you, a man is constructing a portrait of the Virgin Mary out of clumps of elephant dung and snippets of pornography. In the next room, you see a group of men straining to push a huge concrete block from one end of the space to the other and then back again, endlessly. As you make your way to a third doorway, you are confronted by a woman on her hands and knees who whips her long wet hair (which she has dipped in cheap dye) at your feet, driving you backwards. Suddenly, she turns away and begins to gnaw at the corners of a 272-kilogram (600-pound) cube of chocolate, spitting each mouthful into a heart-shaped box. You manage to slip past her and begin running down a long corridor, catching glimpses of what occupies each of the rooms that are open on either side of you: a man pouring blood into a clear mould that resembles his own head a long queue of people waiting to be stared at by an expressionless woman a skull fashioned from diamonds a man with his hand on a switch, turning the lights on and off again every five seconds. You eventually find an exit and push the doors open, hoping to escape the maze. But as soon as you step outside, you are paralysed by the sight of an enormous steel spider, 10 metres (33 feet) in height, towering above you and, behind that, a West Highland Terrier, 12 metres (40 feet) tall, whose colourful fur is made out of living flowers

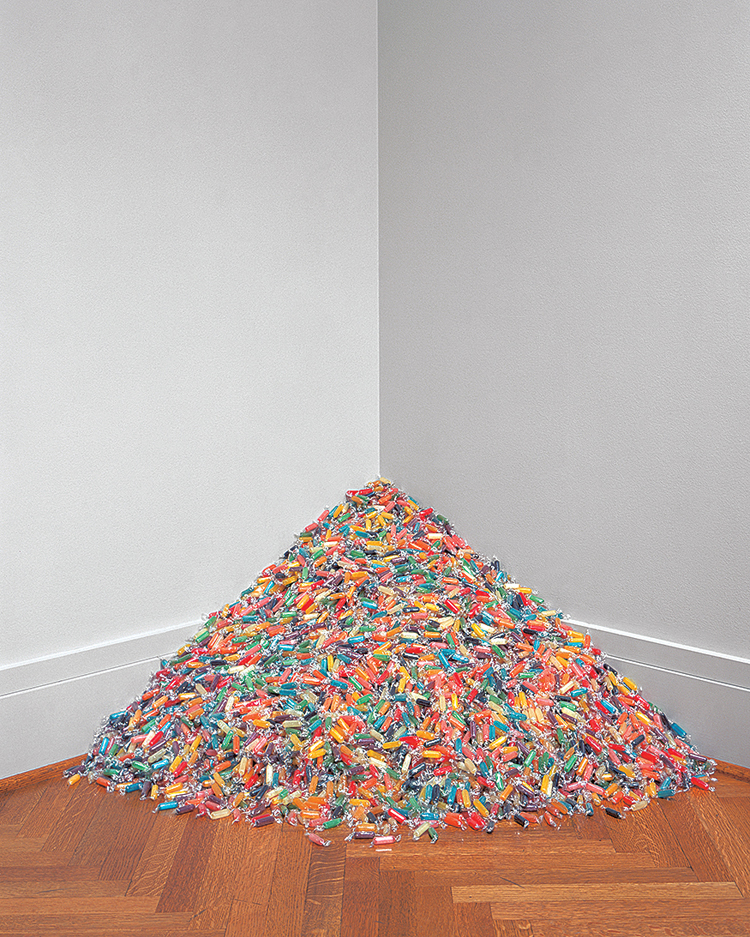

Welcome to the exhilarating, bewildering and, at times, terrifying world of contemporary art. No era in the history of human creativity has ever been so diverse in its vision or so seemingly disconnected in its achievement than the one in which we currently live. Although individual paintings by Raphael, by Michelangelo and by Leonardo da Vinci may reveal the temperament and unique brushwork of the artist who created them, when seen together the works of these three masters, however distinctive, are aesthetically consistent and all belong unmistakably to the same High Renaissance moment. They sing, as it were, from the same historical hymn sheet. But what single score could hope to harmonize the discordant voices, say, of the world-weary flesh of British painter Lucian Freuds later portraits and the steep heap of cellophane-wrapped candies that comprises Cuban-born Felix Gonzalez-Torress conceptual installations? What can possibly unite into a coherent narrative the motivations behind American artist Robert Gobers sculpture of a Winchester rifle melted across a plastic basket filled with Granny Smith apples and French multimedia artist Pierre Huyghes intimate archaeologies of insects entombed in amber? How are we to square the vision of controversial Belgian artist Wim Delvoye, who tattoos the backs of living pigs with a filigree of intricate design, with that of American artist Dale Chihuly, who has transformed the field of blown glass with his sprawling Chandeliers of sinuous fronds?

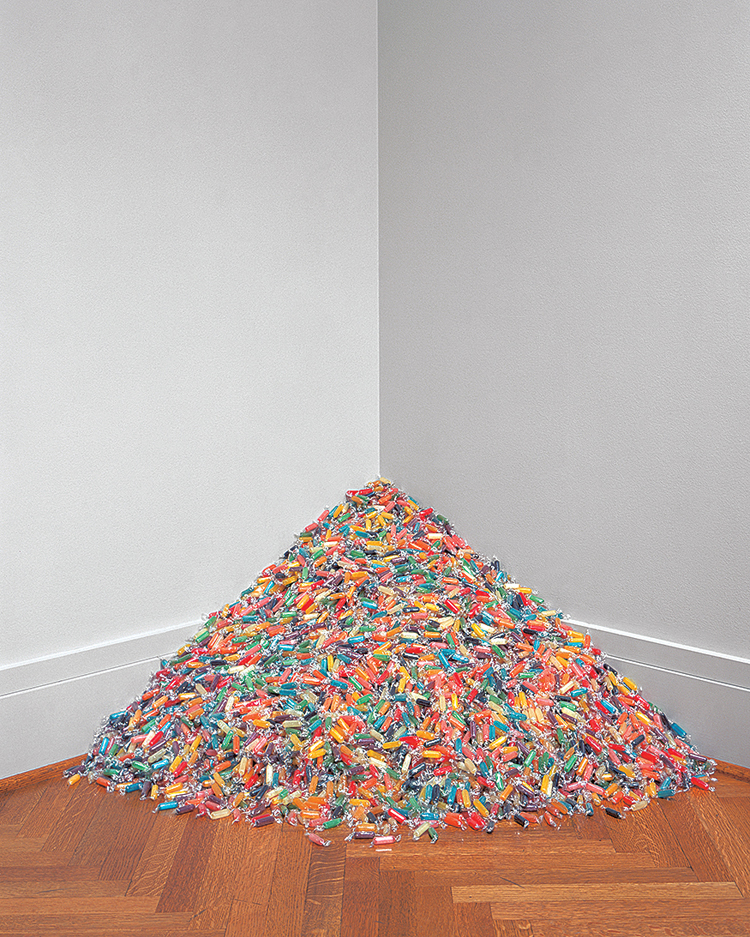

3 Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled, 1992. Candies individually wrapped in variously coloured cellophane, endless supply. Installation view of A Day Without Art, St Louis Art Museum, St Louis, MO. 29 November3 December 2002

Our story begins at a moment of extraordinary upheavals around the world. It starts in that most astonishing stretch of months that bridged the political cataclysms of 1989 and the unprecedented scientific and technological awakenings of 1990. If 1989 saw one era of human history come to an end with the collapse of the Berlin Wall, student protests in Beijings Tiananmen Square and the wave of democratic revolutions that swept across Eastern Europe from Czechoslovakia to Poland, Hungary to Romania the ensuing twelve months witnessed the dawn of a new cultural epoch without obvious parallel in the story of mankind. It was in the year 1990 that our knowledge of the universe would be changed forever with the launch of the Hubble Space Telescope, that our understanding of the very fabric of our bodies would be sharpened immeasurably with the unveiling of the Human Genome Project, and that our ability to communicate with one another and to share information would be utterly transformed with the introduction of the World Wide Web. It is against this tumultuous backdrop that all of the works explored in the following pages came into existence.

Next page