On the Brink:

The Inside Story

of

Fukushima Daiichi

by

Rysh Kadota

Translation: Simon Varnam

Technical supervision: Akira Tokuhiro

Kurodahan Press

2014

Contents

!

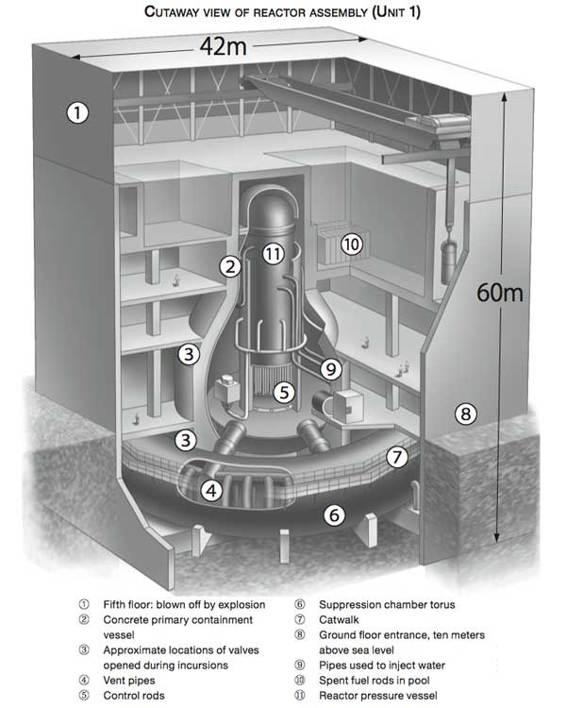

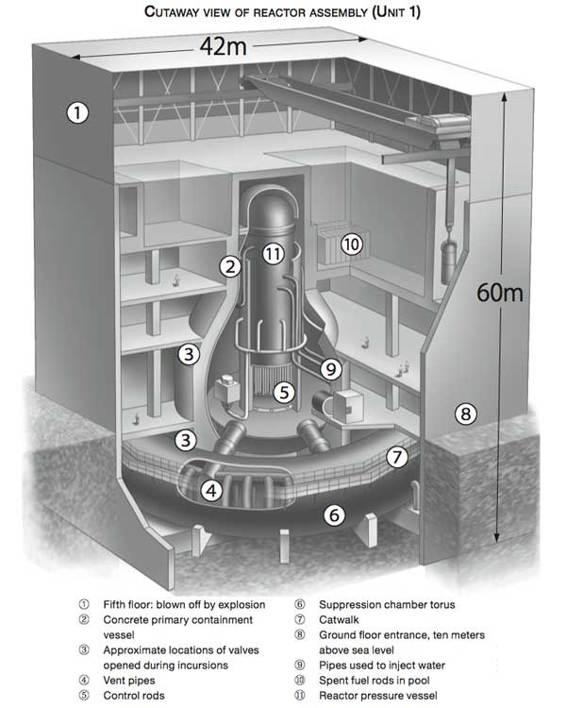

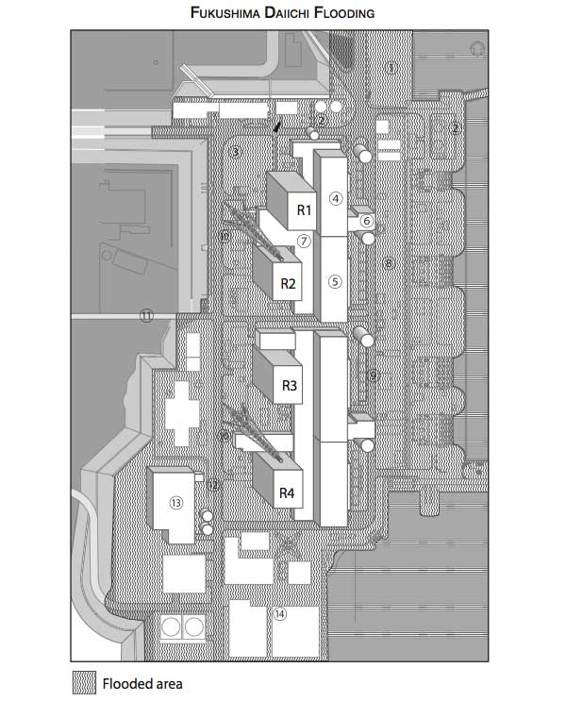

N.B. For clarity, this diagram is greatly simplified and not strictly to scale. Many of the empty spaces are actually crammed with piping, wiring, access ladders, and miscellaneous equipment.

2012 Tomonori Kodama

Acknowledgments

This book has come to fruition only through the efforts of a huge number of people.

Starting with Masao Yoshida, Site Superintendent at FDI, I must also mention the employees of TEPCO and contracted companies who labored on at the plant, the self-defense forces personnel who mobilized, the politicians and government officials who organized emergency responses, researchers, local journalists, evacuees, the relatives of those who died in the accident, and countless others whose kind contributions have enabled the completion of this book.

The truth of this unforeseen disaster must be passed on to future generations.

This was the common goal of all the contributors. It was only the enthusiasm of these generous souls that pushed me on and enabled me to overcome the numerous trials and tribulations of completing the book.

During the interview process, I discovered unexpected difficulties and moving human drama largely unknown to the world.

While penning this documentary, I keenly felt that there are times when people have to risk their lives.

The men who made the incursions into the reactor building had families. If these breadwinners had died, their families would have been left destitute, with their futures in doubt.

Nevertheless, they resolved to act. The soldiers, too, though the accident was none of their doing, ignored the danger to their own lives and carried out their missions in the radiation-contaminated area.

The thing that surprised me most when I interviewed them about their roles was that they regarded the work as a matter of course, and even now wouldnt dream of being so vain as to brag about the experience. In fact, though they were among the first responders, bringing their fire engines to initiate recovery of the plant, they themselves were surprised that I should come specially to talk with them about it.

We only did what was expected of us. I doubt that many, even in the forces, have even heard about the operation we carried out there.

The TEPCO employees at the plant and the people working for contracted companies too, the people who carried on working as radiation levels rose; all had the same kind of attitude toward their work, something which I found both surprising and deeply moving.

I have written a number of books related to the Pacific War. In them, I have referred to the generation that supplied the main fighting strength of the nation the generation born in the Taish era (1912-26) and which suffered more than two million dead, as the generation that lived for others. In contrast, I have criticized the current generation as one that lives for itself alone.

However, one unexpected thing that the tragedy of this nuclear accident has taught me is that the people of Japan retain the same sense of dedication and responsibility as their forebears, facing their problems with resolution, even to the point of risking their lives.

Besides the reality of the tragedy of this nuclear catastrophe, I hope this book has also shown the true power and conviction that people in desperate circumstances can find in the eleventh hour.

A question that occupied me throughout the collection of material for this book was how they were able to push themselves so far. I will be delighted if this book enables readers to find the answer to that question.

I must apologize for not naming all of the people who contributed to this book in so many ways; their number is huge. For the fact that this non-fiction book has reached publication, I offer my deepest thanks to all of them.

Rysh Kadota

Introduction

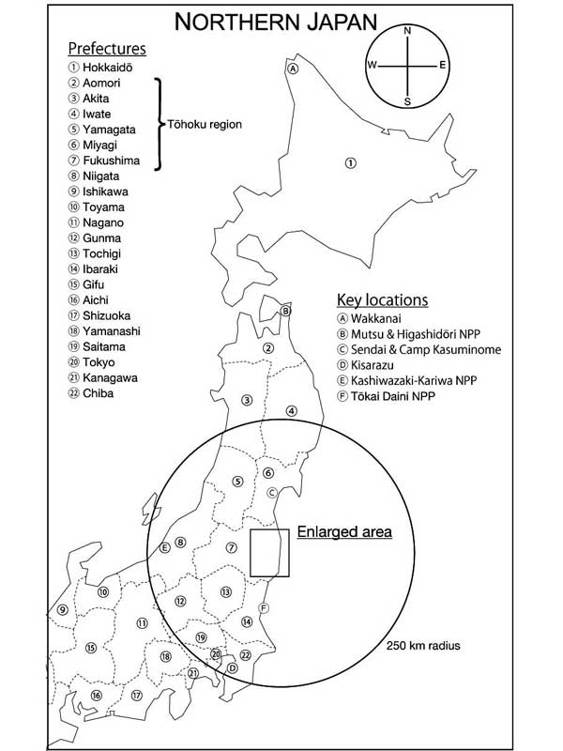

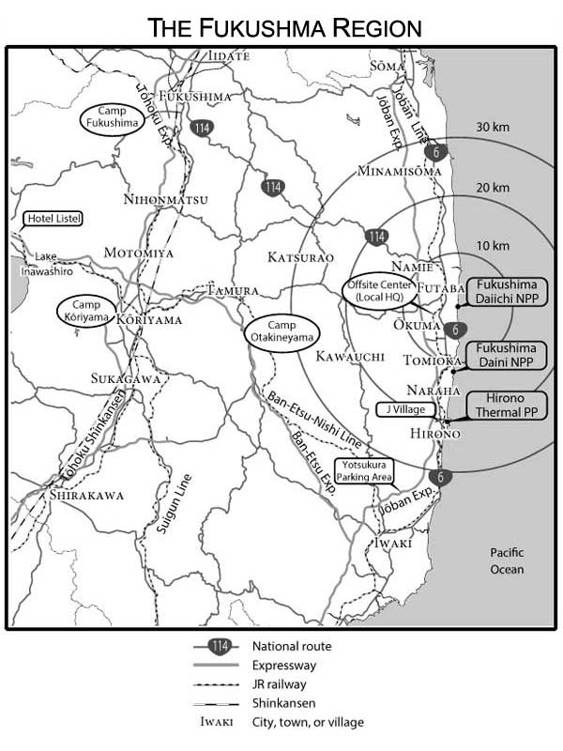

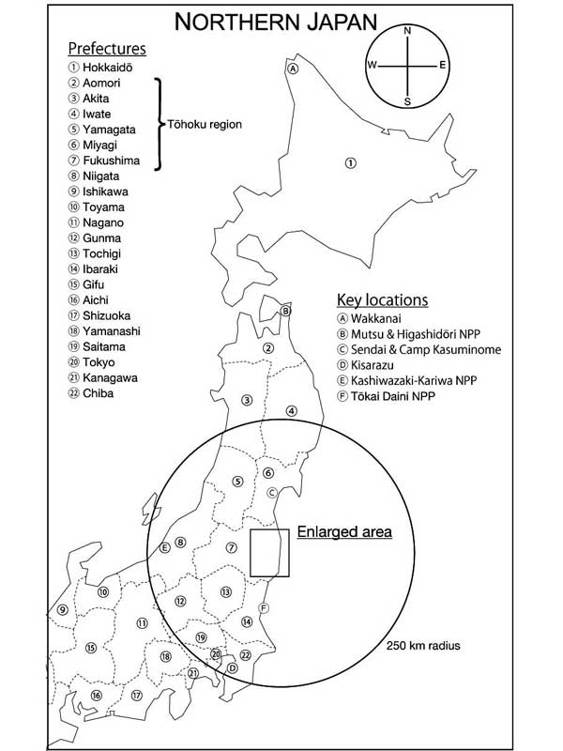

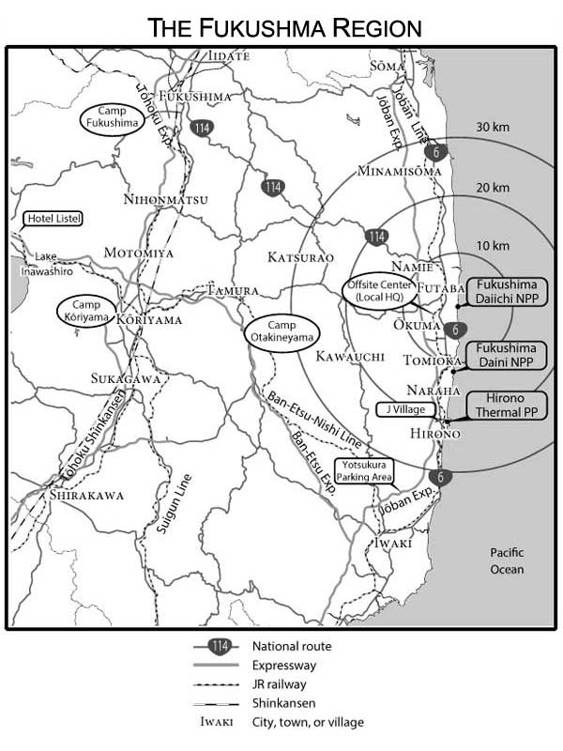

The accident at Fukushima Daiichi has wrought unprecedented tragedy not only on Fukushima prefecture but on the whole of the northeastern Thoku region of Japan, while the aftereffects drag on even now, a year and a half after the earthquake. No one can say when the situation will be resolved.

People are anxious and angry. The sufferings of people who have had to abandon their hometowns, ordered to evacuate as if in wartime, and who still live in temporary housing or rented apartments, cannot be described with platitudes. Few find it easy to discuss their feelings on being forced to leave the land of their birth.

Fifteen months after the earthquake, Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), the company responsible for the accident, was effectively nationalized. It was already impossible for such a private enterprise to cover the enormous costs of compensation to the victims. Japans largest power company, recognized as a symbol of Japans prosperity, disappeared, to be reborn as a new company.

But within this series of events there was one aspect missing that I felt I simply had to know, and that was the human side of it all. In this, the most desperate situation imaginable, what actually happened on-site? How did they feel? How did they cope?

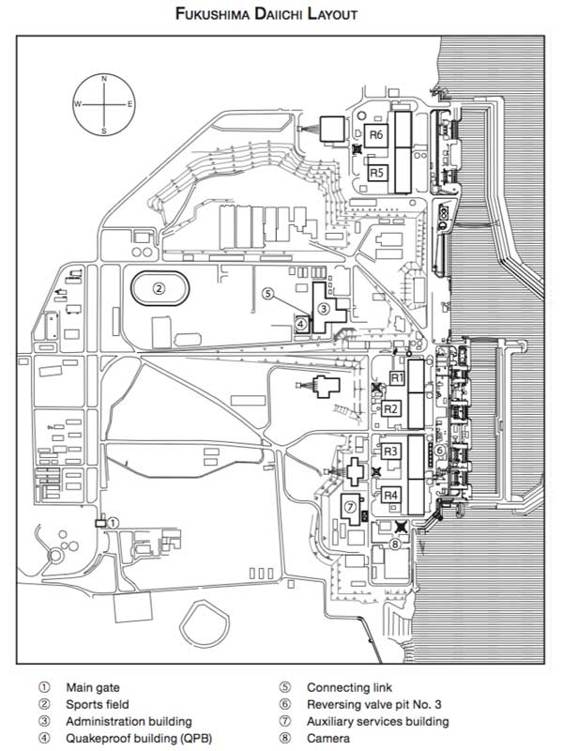

First they learned of a total power blackout, next an inoperative cooling system, rising radiation levels, and then hydrogen explosions this kind of data coming in, minute by minute, must have banished all hope. With no way to cool the reactors they were on the verge of running amok, but many of the staff remained on-site to do what little they could. Though the news that reached the public was fragmented and infrequent, the image that we, the Japanese public, got was that a few brave people had remained at the plant and were struggling to control the situation. The vision of people battling on in the darkness of a total blackout was beyond our imagination. We had a vague image of TEPCO employees, contractors staff, even members of the military, who came and risked their lives large numbers of people holding out in the midst of the radiation but it was almost impossible to discern the human situation on site. Technical assessments and evaluations of the disaster have been issued since by independent bodies, by TEPCO, by the Diet (the Japanese Parliament) and by various government bodies, but none of them touches on the human aspect.

Soon after the accident, I started to approach TEPCO itself, the relevant government agencies, and local sources, in an attempt to pursue the matter, but there seemed to be a thick wall of silence that repeatedly rebuffed me. Though I struggled on with my research, it wasnt until the beginning of 2012 that a vague outline of the reality began to appear. Id had a suspicion from the start, but the truth was far worse than I had imagined.

In the face of extreme adversity, peoples strengths and weaknesses are exposed. Someone unremarkable may, at the moment of truth, reveal hidden strengths, while another who has always spoken noble words may, when it comes to the crunch, become a figure of shame.

Next page