Re-Imagining Japan after Fukushima

-Tamaki Mihic

Asian Studies Series Monograph 13

Published by ANU Press

The Australian National University

Acton ACT 2601, Australia

Email: anupress@anu.edu.au

Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au

ISBN (print): 9781760463533

ISBN (online): 9781760463540

WorldCat (print): 1140933891

WorldCat (online): 1140933873

DOI: 10.22459/RJF.2020

This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode

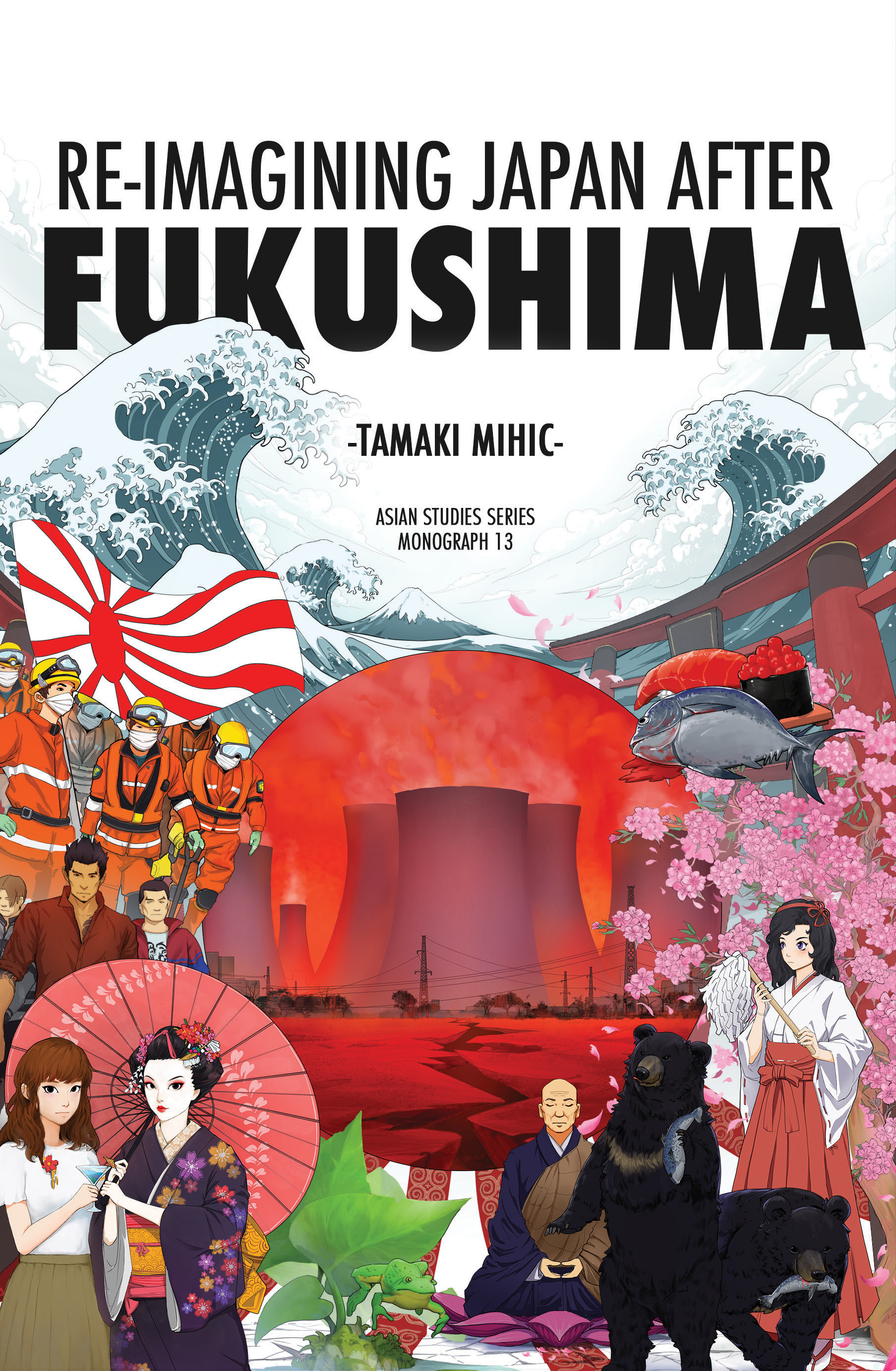

Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover artwork by Viart Studios, 2019.

This edition 2020 ANU Press

Acknowledgements

This book started as a PhD project under the supervision of Dr Rebecca Suter at the School of Languages and Cultures, University of Sydney, from 2013 to 2016. Although I am responsible for the arguments presented in this book, Dr Suters insightful feedback and guidance throughout the years were indispensable in its creation. From when I arrived at her office as a 20-year-old, she has been a constant source of academic inspiration and career mentoring. I cannot thank her enough.

I would also like to thank my three thesis examiners, Dr Marc Yamada, Dr Fabien Arribert-Narce and Dr Christophe Thouny, who went over and beyond their task by making suggestions for how to turn my thesis into a book. My PhD was generously funded by an Australian Postgraduate Award and was also supported by two grants from the School of Languages and Cultures, through the Postgraduate Research Support Scheme.

From 2017 to 2019, I significantly revised my manuscript by thematically re-organising my material. I also added sections on two 2016 films, Kimi no na wa and Shin Gojira, which are discussed in Chapters 3 and 5, respectively. I was able to work on this manuscript using the research time given to me by the University of Sydney as a full-time employee. During this process, I received detailed and insightful guidance from two anonymous reviewers, as well as the editor of the ANU Press Asian Studies Series, Professor Craig Reynolds. I was also fortunate to receive a Capstone Editing Early Career Academic Research Grant for Women in 2018, which paid for copyediting costs. Many thanks to Dr Lisa Lines from Capstone Editing and Emily Tinker from ANU Press for their meticulous attention to detail and editing work.

Parts of Chapters 1 and 2 have appeared in the Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, under the title The Post-3/11 Quest for True KizunaShi no tsubute by Wag Ryichi and Kamisama 2011 by Kawakami Hiromi (2015). I am very grateful to the two anonymous reviewers as well as the journal editor, Dr Laura Hein, for their valuable feedback. Another part of Chapter 4 has been published in the Japanese Studies journal and I would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for this paper as well as the journal editor, Dr Carolyn Stevens, for their well-informed comments.

Last, but definitely not least, I would like to thank Sava for his endless support and encouragement. If you are a non-Japanese speaker or a non-academic, you have him to thank for the numerous English-language definitions and explanations I have added following his reading of the manuscript.

Note on Names and Terms

Foreign words from the Japanese or French languages have been indicated in italics, with translations provided in square brackets. Word-to-word translations of foreign-language titles in the reference list have also been provided in this way. In the case of books already translated into English, I have placed the title of the English-language publication in the square brackets, using italics to indicate this. For foreign terms (identified by italics), square brackets are used to provide English equivalents, while round brackets are generally used when the term does not have a close equivalent in English, to provide explanations or translations that are contextually most appropriate.

The Hepburn system of romanisation is used throughout for Japanese terms, with long vowels indicated by macrons, except for words that have been appropriated into the English language, such as Tokyo or Kyoto, or when referring to characters whose names appear without macrons in the original text. I have avoided the use of Japanese characters in the main text unless necessary.

Throughout the main body of this book, the Japanese convention that the surname precedes the first name is respected with regards to Japanese authors who publish primarily in Japan. Uncertainty may be resolved by referring to the reference list, in which all authors are listed by their surnames, regardless of their cultural heritage.

All quotations from texts in foreign languages are my translations unless otherwise identified.

Introduction

The Thoku earthquake and tsunami that hit Japan on 11 March 2011 (3.11) was an event of unforeseen proportions. A magnitude 9.0 earthquake was followed by 9.3-metre-high tsunami waves over the coast of north-eastern Japan, which claimed the lives of nearly 20,000 people and obliterated communities. The earthquake began at 2.46 pm, which meant that most children were at school and were guided to higher ground in anticipation of a tsunami. Over 240 children were orphaned as a result. Numerous medical and administrative institutions were destroyed when they were most needed and 160,000 people were forced to move to temporary shelters. However, the disaster did not end therenearly 700 aftershocks of magnitude 5 or greater were recorded within a year of 3.11 (Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, 2012). Further, 3.11 developed into a triple disaster, with the subsequent meltdown of three nuclear reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi power plant, which caused 344,000 people to evacuate from the affected areas (Reconstruction Agency, 2012). Many continue to suffer, especially from the effects of the nuclear disaster, while the rest of the nation attempts to move on. There is no doubt that 3.11 has left a permanent scar on the lives of manyeven if they did not lose their friends and loved ones, they lost their livelihood, their homes and their lifestyles.

In the foreign media, perhaps the most memorable images from the disaster were Japanese people calmly lining up to receive supplies or waiting for the public transport system to resume without any outward display of stress or anguish, despite the shock of the disaster. Perhaps they were the pictures of the widescale debris removal that was accomplished one year on, which has often been compared to the state of reconstruction in post-quake Haiti. These images reinforced age-old foreign stereotypes of the hardworking, resilient and orderly Japanese and were widely accepted by Western audiences. However, did the Japanese feel the same way? Some Japanese were inspired by these foreign images to live up to this ideal and restore their pride in a country that had been ageing and slowly dwindling in global economic and technological influence, while their Asian neighbours seemed to prosper. Conversely, many Japanese felt that this portrayal masked the real issues of the disaster: the ongoing nuclear disaster and radiation damage, the discrimination against Fukushima residents, fishermen and farmers that resulted from it, the socioeconomic gap between the disaster-hit northern areas versus Tokyo and the insularity and secrecy of the nuclear power industry.