To my grandchildren, Elon, Eliana, and Alex, and to all young readers whose work and votes will shape our energy future F.B.

Copyright 2012 by Alfred B. Bortz

All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.

A division of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc.

For reading levels and more information, look up this title at www.lernerbooks.com.

Main body text set in Bembo Std 12/15.

Typeface provided by Monotype Typography.

Bortz, Alfred B.

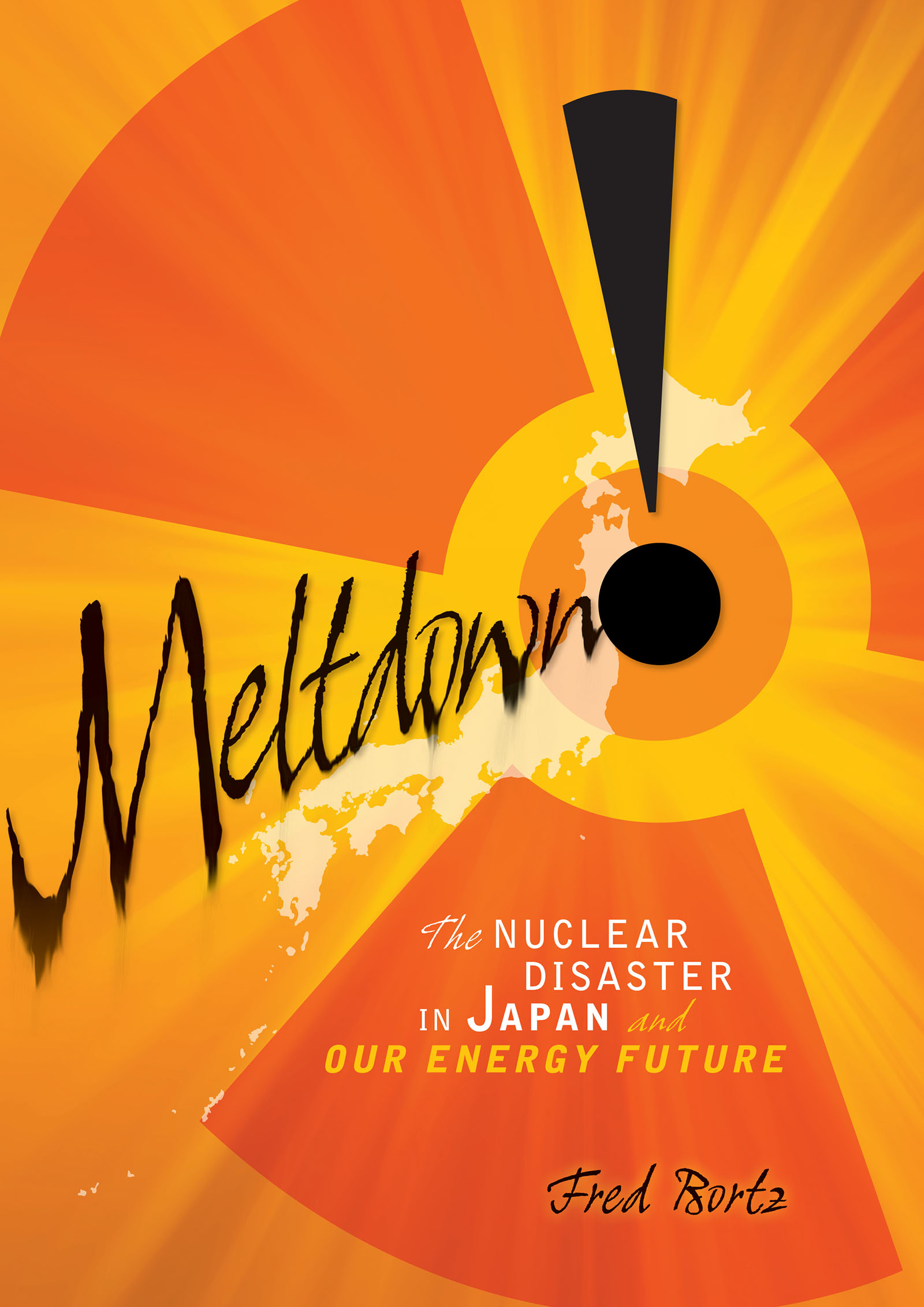

Meltdown! : the nuclear disaster in Japan and our energy future / by Fred Bortz.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9780761386605 (lib. bdg. : alk. paper)

1. Nuclear power plantsAccidentsJapanFukushimaken. 2. Nuclear reactor accidentsJapanFukushimaken. 3. Boiling water reactorsAccidentsJapanFukushimaken. 4. Nuclear energySafety measures. 5. Tsunami damageJapanFukushimaken. I. Title.

CONTENTS

Prologue: Japans Greatest Quake

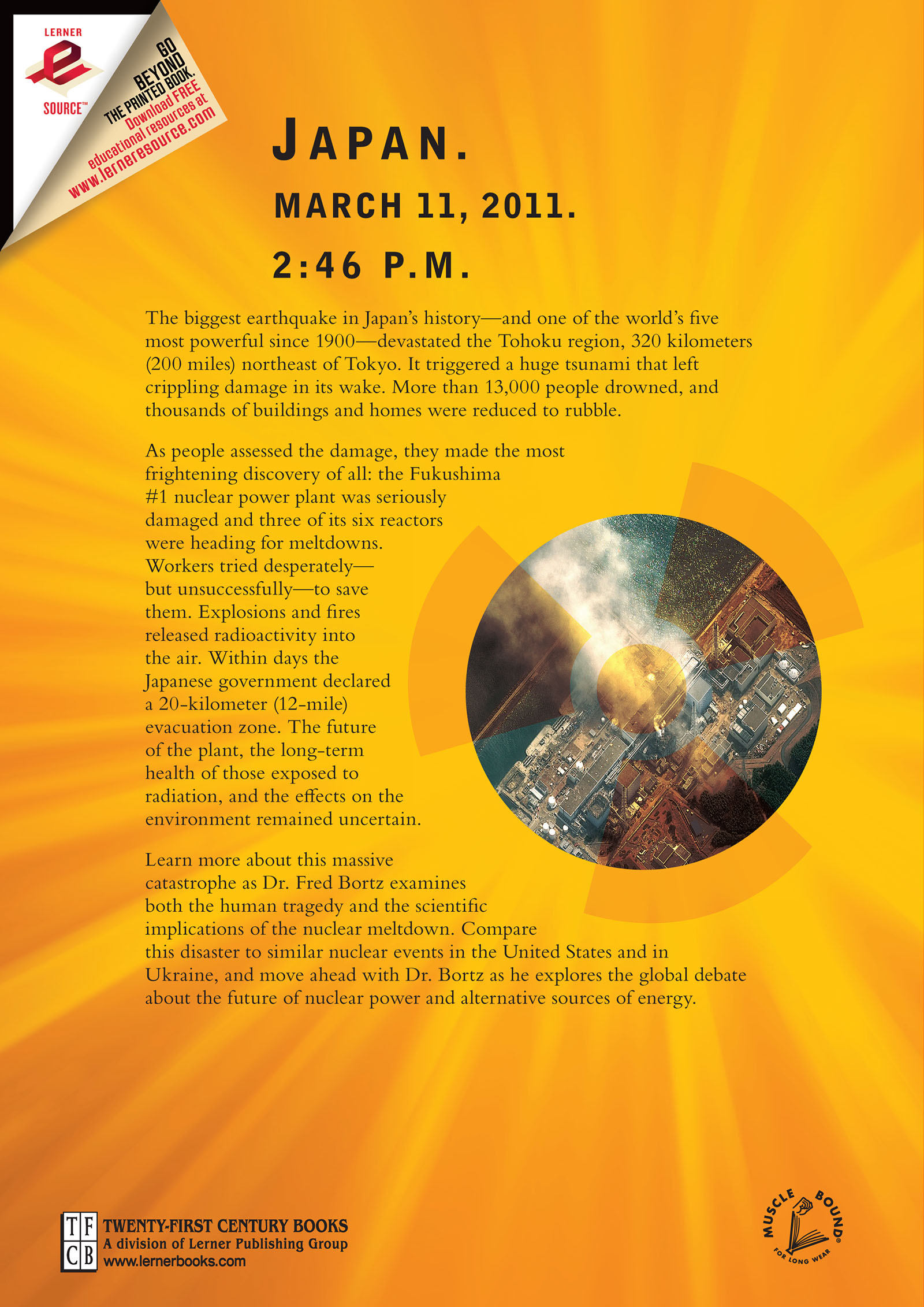

Japan.

March 11, 2011.

2:46 p.m.

An earthquake strikes.

Arun Vemuri is not frightened when he feels his Tokyo office on the thirtieth floor of the Yebisu Garden Place Tower begin to sway. He knows that the building is one of the safest in the city. Like other Japanese buildings, it is designed to bend in an earthquake instead of breaking. So for the first minute, he is smiling at his coworkers and having a swinging good time.

Then the swaying turns into wild shaking. Office equipment topples, and the jolting motion sweeps desks clear. Arun ducks under his desk.

After six long minutes, the shaking stops. Arun and his colleagues leave the office and head down thirty flights of stairs. No one seems anxious or fearful. No rushing of feet or stomping of ground. No racing through or overtaking. Just a good old smiling saunter as if going down for a quick cup of coffee.

No Ordinary Earthquake

Similar scenes are taking place all over Tokyo (above left) . Though almost everyone seems calm, they know that this is no ordinary earthquake. Because the shaking lasts so long and skyscrapers are still swaying, this has to be a big one. The most worrisome question is this: is the quakes epicenter (the place on Earths surface directly above the underground spot where a quake begins) on land or in the ocean? An undersea quake could unleash a tsunami (a Japanese word for harbor wave), a powerful destructive wall of water rushing in from the sea.

Everyone scrambles for information. Most cell phone service is out, but the Internet is working. Twitter is buzzing with news of earthquake damage and a powerful tsunami rolling into the Tohoku region at the northern end of Honshu, Japans main island.

Within hours, horrifying pictures and video are spreading around the world. Almost thirty thousand people in Japan are dead, injured, or missing, mostly from the tsunami.

The Great Tohoku Earthquake is the most powerful ever to strike Japan, and the tsunami makes it one of the worst disasters in that island nations history. Yet in some ways, it is a familiar event for Japan, where earthquakes are common. The Japanese people know what it takes to recover from earthquakes and tsunamis.

Nuclear Emergency!

What people do not yet know is that a much greater and more terrifying challenge lies ahead. That evening, news begins to spread about an emergency at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant about 260 kilometers (160 miles) northeast of Tokyo. The government of Fukushima Prefecture (state or province) warns people who live within 3 km (2 mi) to leave.

Japanese chief cabinet secretary Yukio Edano tries to reassure the public. We have declared a nuclear emergency state to take every possible precaution, he declares at a news conference. There is no radiation leak, nor will there be a leak.

He could not be more wrong. One reactor is already undergoing a meltdown, and two others will soon follow. It is the beginning of a disaster that will change life in Japan and alter the worlds energy future.

Chapter 1

Earthquake! Tsunami! Meltdown!

Although it strikes suddenly, the Great Tohoku Earthquake has been building up for hundreds of years. Like all quakes, it happens because Earths outer rocky layer, called the crust, is made up of many large, slow-moving pieces. These are called plates.

The crust lies above another rocky layer called the mantle. The mantle is so hot that it is not completely solid. It flows in giant loops from Earths core to the crust. The pattern is the same one you can see in a pot of boiling water on a stove. But the movement is much slower because the mantle is made of rock.

At the top of the mantle, different loops flow in different directions. The flowing mantle drags the crust with it. That explains the cracking and movement of the plates.

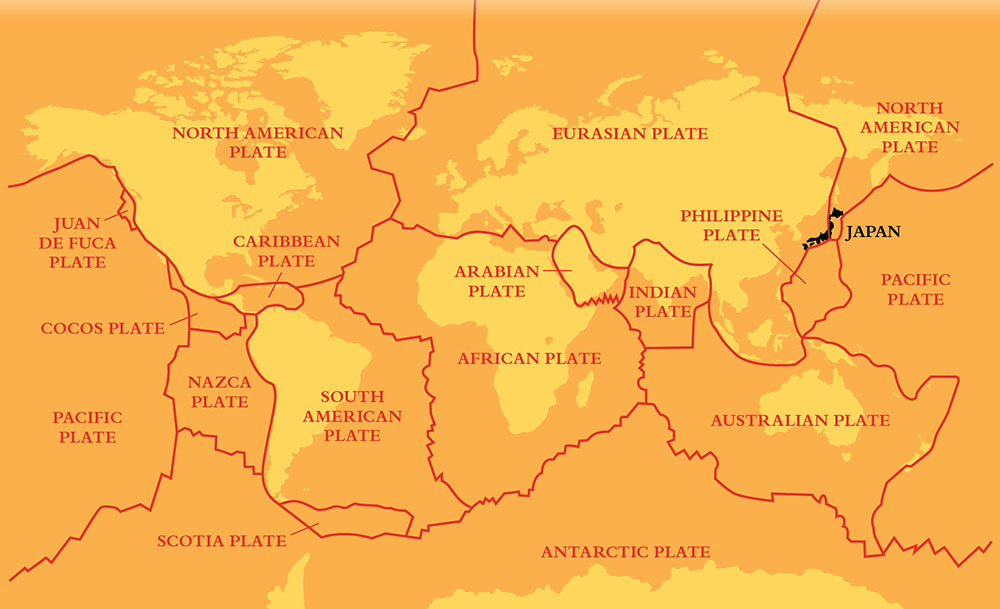

Most of the Pacific Ocean lies above the Pacific Plate. Japan sits just west of the Pacific Plate on three other plates. Those are the North American Plate to the north, the Eurasian Plate to the west, and the Philippine Plate to the south.

This map shows Earths plates. Japan straddles three plates. Moving and shifting plates cause earthquakes. Millions of earthquakes have rocked Japan over the centuries, such as the Great Tohoku Earthquake in March 2011 that devastated the country.

Earthquake!

Year after year, the Pacific Plate moves about 8 to 9 centimeters (3 to 3.5 inches) closer to Japan. Thats about half as fast as your hair grows. It plows under the North American Plate and the Philippine Plate off the east coast of Honshu, Japans main island.

The rocks of the Pacific Plate lock with the rocks at the edges of the plates above it. That bends the upper plates downward. With every centimeter that the Pacific Plate moves, the upper plates bend more. With every centimeter, the force on the locked rocks grows. Finally, that force becomes more than the locked rocks can handle.

The rocks start to crack, crumble, and split apart. That increases the force on other nearby rocks even more. Those rocks also break apart. All along the line joining the plates, the cracking quickly spreads. That releases the bending force, and the edge of the top plate springs upward 5 to 8 meters (16 to 25 feet).

That is how the Great Tohoku Earthquake begins. Its underground starting point, called the focus, or hypocenter, is about 32 km (20 mi) beneath the epicenter on the ocean surface.