THE FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR POWER PLANT DISASTER AND THE FUTURE OF RENEWABLE ENERGY

NAOTO KAN

PRIME MINISTER OF JAPAN (20102011)

Mario Einaudi Center for International Studies

Distinguished Speaker Series

March 25, 2017

Cornell University

CORNELL GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES

CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS

Ithaca

CONTENTS

Naoto Kan spoke at Cornell University as part of the Mario Einaudi Center for International Studies Distinguished Speaker Series. His public lecture was delivered in Japanese. The text was translated for publication by Brett de Bary.

IT HAS NOW BEEN SIX YEARS since the accident at Japans Fukushima Daiichi Power Plant. A year and a half after its occurrence, I published the book, My Nuclear Nightmare: Leading Japan Through the Fukushima Disaster to a Nuclear-Free Future , based on my experience as Prime Minister of Japan at the time of the accident. The English translation of this book has just been published by Cornell University Press and I am deeply grateful. The book offers an account of the situations I faced at the time of the accident, focusing especially on what I confronted during the week that began on March 11, 2011. I would be very pleased if you find my account of what actually happened during this time instructive.

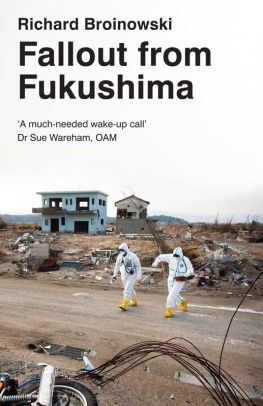

The Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami

The Great East Japan Earthquake erupted without any warning at 2:46 in the afternoon of March 11, 2011. At that moment, I was attending a meeting of the Audit Committee in our Diets [Parliaments] Upper House. No sooner had the committee chair announced the recess of the session than I raced to the Crisis Management Center in the Prime Ministers offi ce complex beside the Diet Building. There, reports about the earthquake and tsunami were pouring in in rapid succession. According to these initial reports, all nuclear power plants in areas where the earthquake had occurred had been shut down successfully.

In nuclear power plants, control rods can be automatically inserted between the fuel rods to halt a nuclear fission chain reaction. However, if earthquake damage makes it impossible to insert these rods, there is no way of halting the reaction and a meltdown will occur.

How the accident at Fukushima Daiichi occurred

Despite initial reassurances, about one hour after the earthquake we received another report which announced that the tsunami that followed the earthquake had disabled not only the electrical generators outside the Fukushima Daiichi plant, but also the diesel-fueled equipment intended for emergency back-up use. This meant there was a total loss of power at the plant.

Soon after, we received further news that the cooling system throughout the plant had shut down. I still remember the chill that ran down my spine when I heard this. I am not a specialist in nuclear energy, but as a university student I majored in applied physics and had gained knowledge of the fundamentals of the field. In a power plant, even when nuclear fission chain reactions have been stopped, the decay of nuclear fuel will continue to create massive amounts of heat for a considerable period. I knew that if the cooling systems were disabled there would be a meltdown.

Dysfunction at the governments Nuclear Emergency Response Headquarters

By Japanese law, in the case of a severe accident in which the cooling systems of a nuclear power plant have been disabled, a Nuclear Emergency Response Headquarters is to be set up with the Prime Minister as its head. The Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency (NISA) within the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI) oversees this disaster headquarters. The reasoning behind this is that the Prime Minister, as a politician, is generally not a specialist in nuclear energy, so a system is in place for government offi cials who are experts to offer him support.

Therefore, after the accident occurred I immediately summoned the director-general of NISA to obtain his views on three questions. What was the nature of the situation we were facing? How was it likely to develop? What measures should be taken? As it turned out, his response made no sense to me and I could not grasp the gist of his explanations. When I asked him if he was an expert in nuclear energy, this director-general of the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency replied that he was a Tokyo University graduate with a degree in economics!

I was stunned by this answer. Of course, since METI also deals with economic policy, it is not surprising for an offi cial to hold a degree in economics. But how can we make sense of the appointment of an economist to be director-general of an agency charged with responding to nuclear accidents? One can only conclude that the assignment of personnel within METI was based on the assumption that a severe nuclear accident would never occur in Japan. Two days later, government offi cers with expertise in nuclear energy transferred into NISA from other agencies and came to consult with me. It was only at that point that I was able to receive an informed assessment of the situation.

Worsening impact of the accident

Since many politicians and government offi cials have had experience in dealing with natural disasters like earthquakes and tsunami, they were able to propose response measures quite rapidly. However, there was not a single person among us who had previously dealt with what is classified as a severe accident at a nuclear power plant. I received words of advice from members of the Nuclear Safety Commission as well as from members of NISA. I had requested that the head of the Nuclear Safety Commission himself attend my meetings, but in the early moments, no information had arrived about the actual circumstances of the accident, and not a single person could shed light on what its consequences might be. At this stage, I had no choice but to start to set up an organization within my own offi ce to gather information about the accident. My special advisers and executive secretary were at the heart of these activities.

Implications of the accident grow more severe

Over the course of the week following the accident, its consequences increased in gravity. First, after the emergency generators had been disabled by the initial impact of the tsunami, I received a request from TEPCO [the Tokyo Electric Power Company] to coordinate with them in the dispatch of power supply trucks to the site. Since the earthquake had left many highways impassable, I called on police to help with this task. When, at 10 p.m. on the night of March 11, the day of the earthquake, we finally succeeded in getting power supply trucks to the plant, we rejoiced. Yet before long, we received word that the plugs in the trucks could not be connected to the plant. Although we did not understand the problem, ultimately the power supply trucks were useless, and we could not restore power.

At midnight that same night, word arrived that steam pressure was building up inside the containment vessels [also called containment buildings, these are lead structures enclosing a nuclear reactor and its fuel rods] in the Number One Reactor, and that it would be necessary to release pressure from the vessels. Since radioactive matter would be released together with the steam, however, there was a possibility of harming area residents.

The Nuclear Emergency Response Headquarters, which would be responsible for evacuating residents in such a situation, had received a request for permission to release the pressure. Let me explain that under ordinary conditions, radioactive material from power plants should never be released into the atmosphere. However, if the containment vessels were to burst because they were unable to withstand the pressure, a very large amount of radioactive material would be released all at once. In the view of the Nuclear Safety Commission, the venting of steam pressure was now necessary in order to prevent the vessels from bursting. On this basis, and in the final hours of the night of March 11, we communicated to TEPCO our understanding that the venting would be carried out.