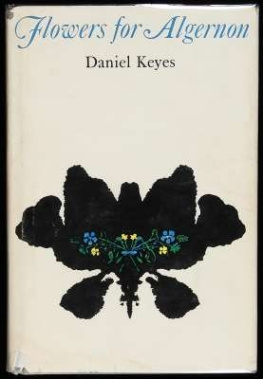

Copyright 1999 by Daniel Keyes

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including

photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without

permission in writing from the publisher.

Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be

mailed to the following address: Permissions Department, Harcourt, Inc.,

6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, Florida 32887-6777.

www.HarcourtBooks.com

First published by Challenge Press, 2000

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Keyes, Daniel.

Algernon, Charlie, and I: a writer's journey/Daniel Keyes.1st Harvest ed.

p. cm.(A Harvest book)

ISBN 0-15-602999-5

ISBN-13 978-0-15-602999-5

1. Keyes, Daniel. Flowers for AlgernonSources. 2. People with mental

disabilities in literature. 3. People with mental disabilitiesFiction.

4. Gifted personsFiction. 5. BrainSurgeryFiction. I. Title.

PS3561.E769F56 2004b

813'.54dc22 2004011445

Text set in AGaramond

Designed by Cathy Riggs

Printed in the United States of America

First Harvest edition 2004

A C E G I K J H F D B

v2.0514

For my wife Aurea,

who tended the dream garden

so "Flowers" could grow.

Contents

P ART O NE THE MAZE OF TIME

1 My Writing Cellar

2 The White Mouse

3 Second Acting

4 Breaking Dishes

5 I Become Ship's Doctor

P ART T WO FROM SHIP TO SHRINK

6 Inkblots

7 The Boy on Book Mountain

8 Silence of the Psychoanalysts

9 First Published Stories

10 Editing Pulps and Writing Comic Books

P ART T HREE MIND OVER MATTER

11 Looking for Charlie

12 Charlie Finds Me

13 Getting There

14 Rejection and Acceptance

P ART F OUR THE ALCHEMY OF WRITING

15 Transformations: From Story to Teleplay to Novel

16 Rejected Again

17 Of Love and Endings

18 We Find a Home

P ART F IVE POST-PUBLICATION BLUES

19 "Don't Hide Your Light Under a Bushel"

20 When Are Writers Like Saints?

21 Charly Goes Hollywood

22 Broadway Bound

23 And Then What Happened?

Afterword: My "What Would Happen If...?" Is Happening

Acknowledgments

FLOWERS FOR ALGERNON

Complete original novelette version

Part One

The Maze of Time

1. My Writing Cellar

I NEVER THOUGHT it would happen to me.

When I was very young and very nearsighted20/400 vision, everything blurred without my eyeglassesI believed that someday I'd go blind. So I planned ahead. I strove to be neat, a place for everything and everything in its place. I blindfolded myself and practiced retrieving things without seeing, and I was proud that I could find anything quickly in the dark.

I didn't go blind. In fact, with eyeglasses my vision is excellent.

I can still put my hands on most things I possess. Not because I remember where I put them, but because I take the time to put them away carefully, in logical places. I just have to remember where they belong. What's happening to me is something I never considered. I start out to do something, go somewhere, walk into another room to get something, but then I have to pause. What am I looking for? Then it quickly clicks into place. It's momentary but frightening. And I think of Charlie Gordon at the end of Flowers for Algernon, saying, "I remember I did something but I don't remember what."

Why am I thinking of the fictional character I created more than forty years ago? I try to put him out of my mind, but he wont let me.

Charlie is haunting me, and I've got to find out why.

I've decided the only way I can put him to rest is to go back through the maze of time, search for his origins, and exorcise the ghosts of memories past. Perhaps, along the way, I'll also learn when, how, and why I became a writer.

Getting started is the hardest thing. I tell myself, you've got the material. You don't have to make it upjust remember it, shape it. And you don't have to create a fictional narrator's voice the way you did for the story and then the novel. This is you, writing about writing, and remembering the secrets of your own life that became the life of Charlie Gordon.

The opening of the story echoes in my mind: "Dr. Strauss says I shud rite down what I think and evrey thing that happins to me from now on. I dont know why but he says its importint so they will see if they will use me. I hope they use me. Miss Kinnian says maybe they can make me smart. I want to be smart. My name is Charlie Gordon..."

Although the original novelette begins with those words, that's not how it all started. Nor are his final words about putting "flowrs ... in the bak yard" the end of his story. I remember clearly where I was the day the ideas that sparked the story first occurred to me.

One crisp April morning in 1945, I climbed the steps to the elevated platform of the Sutter Avenue BMT station in Brownsville, Brooklyn. I'd have a ten- or fifteen-minute wait for the train that would take me to Manhattan, where I would change for the local to the Washington Square branch of New York University.

I recall wondering where I would get the money for the fell semester. My freshman year had used up most of the savings I'd accumulated by working at several jobs, but there wouldn't be enough left to pay for three more years at NYU.

As I took the nickel fare out of my pocket and glanced at it, I remembered my father Willie once admitting to me that when he had been looking for work during the Great Depression, he would walk the ten miles from our two-room apartment, through Brooklyn, and across the Manhattan Bridge each morning and back home each night to save two nickels.

Often, Dad would leave while it was still dark before I awoke, but sometimes I would be up early enough to catch a glimpse of him at the kitchen table, dipping a roll into his coffee. That was his breakfast. For me there was always hot cereal, and sometimes an egg.

Watching him stare into space, I assumed his mind was blank. Now, I realize he was trying to figure out ways to pay our debts. Then he would get up from the table, pat me on the head, tell me to be good in school and study hard. Back then, I thought he was going to his job. I didn't learn until much later that he was ashamed of being out of work.

Maybe this nickel in my hand was one of those he saved.

I dropped it into the slot and pushed through the turnstile. Someday, perhaps I'd retrace his footsteps, walking from Brownsville to Manhattan, to know what it had been like for him. I thought about it, but I never did it.

I think of experiences and images like these as being stored in the root cellar of my mind, hibernating in the dark until they are ready for stories.

Most writers have their own metaphors for stored-away scraps and memories. William Faulkner called his writing place a workshop and referred to his mental storage place as a lumber room, to which he'd go when he needed odds and ends for the fiction he was building.

My mental storage place was in a part of our landlord's cellar, near the coal bin, in the space under the stairs which he allowed my parents to use for storage. Once, when I was big enough to climb down the cellar stairs, I discovered that's where my parents hid my old toys.

I see my brown teddy bear and stuffed giraffe, and Tinkertoy, and Erector set, and tricycle, and roller skates and childhood bookssome of them coloring books with line drawings still to fill in with crayons. For me it solved a mystery of toys that vanished when I'd grown tired of them, and others that reappeared in their place.

Next page