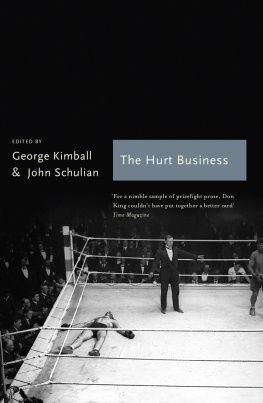

EDITED BY GEORGE KIMBALL & JOHN SCHULIAN FOREWORD BY COLUM MCCANN

AT THE FIGHTS

AMERICAN WRITERS ON BOXING

The Library of America

Introductions, headnotes, and volume compilation copyright 2012 by Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y.

All rights reserved.

No part of the book may be reproduced commercially by offset-lithographic or equivalent copying devices without the permission of the publisher.

Some of the material in this volume is reprinted with the permission of holders of copyright and publishing rights. Acknowledgments begin on .

Distributed to the trade in the United States by Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

and in Canada by Penguin Books Canada Ltd.

A hardcover edition of this book was published by The Librrary of America in 2011.

First paperback editon published in 2012.

THE LIBRARY OF AMERICA, a nonprofit publisher, is dedicated to publishing, and keeping in print, authoritative editions of America's best and most significant writing. Each year the Library adds new volumes to its collection of essential works by America's foremost novelists, poets, essayists, journalists, and statesmen.

If you would like to request a free catalog and find out more about The Library of America, please visit with your name and address. Include your e-mail address if you would like to receive our occasional newsletter with items of interest to readers of classic American literature and exclusive interviews with Library of America authors and editors (we will never share your e-mail address).

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012932714

ISBN 978-1-59853-205-0 (print)

eISBN 978-1-59853-202-9 (ePub)

First eBook Edition: August 2012

Contents

A TRIBUTE TO GEORGE KIMBALL

Last Call

G eorge Kimball was blessed with the kind of voluble charm you find in an Irish bar, and let me tell you hed been in a few. No amount of drink, however, could rein in his galloping intelligence or his love of the language and good company. He was equally engaging in drier precincts, which made him the perfect editing partner for me. When we began doing interviews to hustle this book, George waxed eloquent and I provided grace notes. But slowly, inexorably, his voice became a sandpaper whisper. It was the chemo, extracting its price for keeping him upright.

Now I had to do the talking, a reluctant solo act trying to score points with strangers armed with questions. Again and again I found myself telling them about the nobility of prizefighters, who willingly risk death every time they step into the ring. But it was always George I thought of, the truest nobleman of my lifetime.

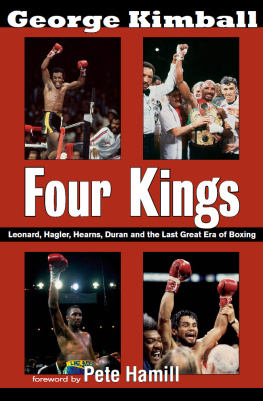

The cancer doctors gave him six months to live in 2005. He spent the next six years making liars of them. Not only did he publish Four Kings, a masterful book about boxings last golden era, he covered fights online and wrote essays, poetry, songs, and even a play. He edited books, too, obviously, and worked on a documentary. Somehow he made time to get to the theater and concerts and dinner, and to France and Ireland as well. He savored the world that was slipping away from him and, with friends old and new, proved forevermore that once he wrapped his arms around someone, he never let go.

Those of us who knew himand probably some who didntwill keep the Kimball legend alive with tales of his wild times and all the nights he dropped his glass eye in a drink some unsuspecting soul had asked him to keep an eye on. At such moments George wore the sublimely demented look I first saw in the Lions Head, the legendary Greenwich Village writers bar, as he tried to light a friends sport coat on fire. His friend was wearing it.

The booze and drugs were behind George by 2009, when he and I began digging for the treasures that grace this book. The only remnant of his old life was the unfiltered Lucky Strikes he smoked ceaselessly. What are they going to do, hed say, give me cancer? He had it by then, of coursethe esophageal varietyand he knew that death would win no matter how hard he fought. But he was damned if he wasnt going to go the full twelve rounds. He was fighting for money he would leave his wife and two grown children and for one last grand achievement to cement his legacy in sports writing. At the Fights was that achievement.

For six months we searched everywhere we could think of, touting our best discoveries, bumping heads over differences in taste, and all the while mailing envelopes fat with stories to be considered back and forth across the country. George was in New York, I was in L.A., and we didnt see each other until that March day in 2010 when our bosses at The Library of America told us our manuscript had passed muster. We celebrated over lunch at a little joint in the East Sixties. George was so happy it didnt matter that he was too sick to swallow his soup.

The question from that point forward was whether he would live long enough to see our book published. He raised it himself, and answered it in word and deed. He reveled in the interviews we did. He embraced readings with Pete Hamill in Manhattan and made his last triumphant returns to Boston, his stomping grounds as a newspaperman, and Kansas University, where he had twice lost decisions to academia. But it wasnt until the publication party, with everyone from his 89-year-old mother to Gay Talese gathered at the New York Athletic Club, that I knew for certain what Id long suspected. The book had helped to keep him alive.

That was in April 2011. Three months later George was dead, at sixty-seven, and a great emptiness set in on those of us who had worked with him, howled at the moon with him, loved him. Our solace comes from the same source that I hope will bring you joy: these five hundred-plus pages of great boxing writing. On every one of them, Georges heart still beats.

John Schulian

COLUM MCCANN

Foreword

B oxing. You can press the language out of it. The sweathouse of the body. The moving machinery of ligaments. The intimate fray of rope. The men in their archaic stances like anatomy illustrations from an old-time encyclopedia. The moment in a fight when the punches slow down and the opponents watch each other like time-lapse photographsthe sweat frozen in mid-air, the blood still spinning, the maniacal grins like the teeth themselves have gone bare-knuckle.

Writers love boxingeven if they cant box. And maybe writers love boxing especially because they cant box. The language is all cinema and violence: the burst eye socket, the ruined cartilage, the dolphin punch coming up from the depths.

What you have with a fight is what you have with writing, and they each become metaphors for each otherthe ring, the page; the punch, the word; the choreography, the keyboard; the feint, the suggestion; the bucket, the wastebasket; the sweat, the edit; the pretender, the critic; the bell, the deadline. Theres the showoff shuffle, the mingled blood on your gloves, the spitting your teeth up at the end of the day.

Literature recreates the language of the epic. And whats more epic and mythological than a scrap? For those of us who cant fight, we still want to be able to step into a fighters body. We want to walk off woozy to the corner and have our faces slapped a little bit, then suddenly get up to dance, and hear the crowd roar, and step out once more with a little dazzle.

Boxers get told to imagine punching a spot behind your opponents head, to reach in so far so they can extend the destruction to the back of the head. Writers do the same thingthey try to imagine a spot behind your brain and punch you there. Boom. Headspin. Skin-slip on the canvas. Ten, nine, eight. Get the fuck up off this page. Four three two one Mississippi. Get the fuck up. Now.

Next page