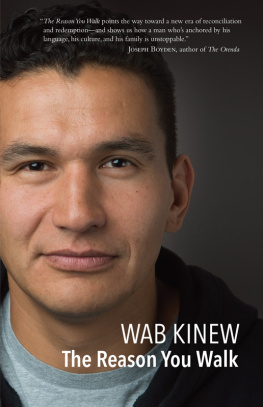

The Reason You Walk

WAB KINEW

The Reason You Walk

Miigwech Nimaamaa, Miigwech Ndede

Ningosha anishaa wenji-bimoseyan

(I am the reason you walk)

Anishinaabe travelling song

PROLOGUE

If you were to enter the centre of the sundance circle, then you would understand the beauty of what happens there.

The shake of the cottonwood trees in the breeze the swing and sway of prayer flags of every colour tied to the branches the chorus of cicadas singing a perfect soundtrack for the sweltering heat the feeling of hundreds of supporters standing on the edge of the circle watching you.

THE HOT SAND was starting to burn my feet. The suns radiance had burrowed deep into my skin, turning it a dark carmine-brown. My dried sweat left a thin layer of salt on my body. I could taste it as I licked my lips.

We had been dancing and fasting in this circle since long before dawn.

Chiefs and headmen formed a procession and walked to the south side of the arbour, where I stood. They took my fathers war bonnet from its perch and raised it toward the sky. The dozens of eagle feathers splayed around the headdress like a halo, each representing an act of valour, while the intricate patterns of glass beads caught the light of the sun. The PA system crackled.

When they brought the war bonnet down from the sky and placed it on my head, war whoops and ululations rose from those around the circle. They had made me a chief.

The sundance leader laid down a small box, opened it, and withdrew a treaty medallion. Placing the medallion in my hands, he reminded me of the significance of the treaty relationship: the commitment to share the land with newcomers. On one side of the medallion was a profile of George Washington. The other showed two hands shaking. One hand was European. The other was Indigenous. We are all treaty people.

I nodded and thanked him. I was surprised by how heavy the medal was in my hands.

I turned my gaze to the earth. It had been two years since I was here last. I had strayed off the red road I had been taught to walk as a boy. I had turned my back on Ndede, my father. I had hurt many people, including those closest to me.

As the son of a hereditary chief, I had always known I would someday rise to this rank, but I assumed that day was far in the future. Perhaps it would arrive after I had achieved something great. Instead, it came when I was at one of the lowest ebbs of my life. My community, my family, and my father responded by giving me a second chance. That which was broken, they tried to make whole again.

All of this took place more than a decade ago. It was not the only time my father would pass something to me that I would commit to carrying into the future.

In the last year of his life, Ndede would go on a remarkable journey of hope, healing, and eventually forgiveness. The journey would take him to the greatest heights of some of the worlds most powerful institutions. Yet, in the end, it would resonate on the most basic level of existence that all of us share.

More than any inheritance, more than any sacred item, more than any title, the legacy he left behind is this: as on that day in the sundance circle when he lifted me from the depths, he taught us that during our time on earth we ought to love one another, and that when our hearts are broken, we ought to work hard to make them whole again.

This is at the centre of sacred ceremonies practised by Indigenous people. This is what so many of us seek, no matter where we begin life.

This is the reason you walk.

Ndede means my father in Ojibwe, a term my sister Shawon and I used growing up to refer to our dad. The e here sounds similar to the e in the word egg. Written phonetically, Ndede sounds something like in-DEH-deh.

PART ONE

Oshkaadizid

Youth

A CLOUD FLEW LOW across the shimmering waters of Lake of the Woods. WaabanakwadGrey Clouda tall, lean Anishinaabe man, studied this bit of mist as it floated by. He broke off a knot of tobacco in his hand and placed the offering on the water. Then he craned his neck upward so that when he spoke, his words rose up into the sky.

Ahow nimishoomis, miigwech kimiinshiyin ningoozis owiinzowin, the man said in Ojibwe. Oh, grandfather, thank you for giving me my sons name.

Newborn twin boys lay nearby with their mother, NenagiizhigokHealing Sky Woman. They nursed in the lodge nestled along the line of trees on a point just north of Turtle Narrows. They had arrived early that morning. Waabanakwad knew they were a beautiful gift. He thought of what a blessing it was that his little family was there on his trapline, on land that had been his fathers and his grandfathers before him.

Tobasonakwut, he said to himself. Low Flying Cloud. He watched his sons namesake drift past and disappear into the fog that obscured the far shore. He crouched by the water seeking another vision, a name for his other son.

The leaves of a poplar rustled softly in the wind. The water lapped near Waabanakwads feet.

That must have been when a small bird landed close to him, cocking its head from side to side, studying Waabanakwad. When Waabanakwad smiled at it, the little apparition jumped into the air. He swooped toward the ground before his wings found their lift and he flew away into the mist.

Bineshii, Waabanakwad said. Little Bird. He liked the name. His eyes crinkled as a smile spread across his face.

He offered the rest of his tobacco, invoked the spirits of the four directions, grandmother earth, and the grandfather of us all, then walked back to his lodge. He had named his sons, and Nenagiizhigok must have beamed when she saw Waabanakwad return to their home.

The smiles would soon vanish. While still infants, both boys were struck by scarlet fever, but the Anishinaabe medicine helped only Tobasonakwut. Bineshii lived up to his namesake. He touched the ground in this world only briefly before taking flight and leaving us for the spirit world.

Years later, when he became a gichi-Anishinaabea giant among his peopleTobasonakwut was told by an elder that he had lived such a rich, intense life because he had experienced not just the rewards and challenges that were rightly his own, but also the pain, joy, and heartache that rightly belonged to Bineshii. Tobasonakwut had experienced enough for two lifetimes. This is probably why the Anishinaabemowin word for twin is niizhote, or two heart. Not two hearts, but a duality embodied in one sacred bond. This is what Tobasonakwut would be told by an elder much later in his journey. Even further down that road, those two hearts would become one again. But that would not be for a very, very long time.

First, there was the business of being a kid.

WHEN STILL A YOUNG GIRL, Nenagiizhigok had been playing one day with her siblings and cousins near Siiamo Ziibing, not far from where her son Tobasonakwut would be born a generation later. It must have been a warm summer day, probably in the morning, when the sun was beginning to bring heat to the forest shade.

The children chased each other, their laughs echoing along the rocky shore. When one of them broke off and ran up a gentle slope into the forest, the others, Nenagiizhigok included, followed. Soon they were in pursuit, slaloming through the pine trees, red-pine needles on the forest floor a soft cushion beneath their moccasins. Though they shouted and giggled, their footsteps were softer on the earth than any of us today could imagine. They broke into a clearing in the woods where tall grasses grew, hiding a swamp beneath them. Beautiful flowers danced among the grasses, swayed by the gentle breeze, and the children were drawn closer and closer, away from the trees.

Next page