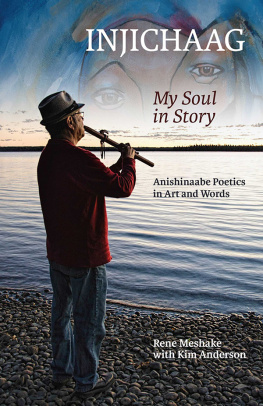

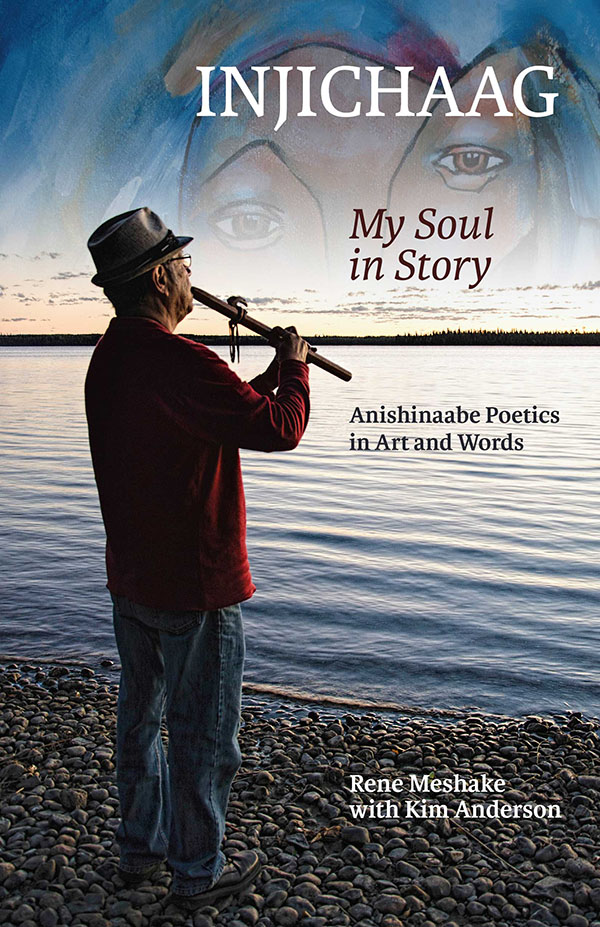

INJICHAAG

My Soul in Story

Anishinaabe Poetics in Art and Words

RENE MESHAKE

WITH KIM ANDERSON

Injichaag: My Soul in Story

Anishinaabe Poetics in Art and Words

Rene Meshake 2019

Introduction and Epilogue Kim Anderson 2019

23 22 21 20 19 1 2 3 4 5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database and retrieval system in Canada, without the prior written permission of the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or any other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, www.accesscopyright.ca, 1-800-893-5777.

University of Manitoba Press

Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Treaty 1 Territory

uofmpress.ca

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN 978-0-88755-848-1 (PAPER)

ISBN 978-0-88755-850-4 (PDF)

ISBN 978-0-88755-849-8 (EPUB)

Cover design: Kirk Warren

Cover photo: Joan Bruder

Interior design: Jess Koroscil

Printed in Canada

The poem Still Here and the story Andjiiana Gitodem were first accepted for publication in The Other Side of 150 , a volume of essays slated to appear in 2020 through Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Awards to Scholarly Publications Program, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

The University of Manitoba Press acknowledges the financial support for its publication program provided by the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Manitoba Department of Sport, Culture, and Heritage, the Manitoba Arts Council, and the Manitoba Book Publishing Tax Credit.

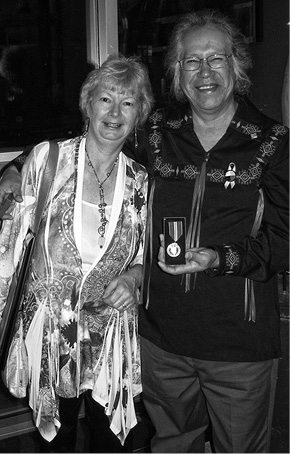

Dedicated to my dear wife Joan and my son Aaron

in whom I am well blessed

Contents

Andotamowin: Invocation

After I settled on Injichaag as the title of my book, I noticed the similarity between inji[chaa]g and ru[ach]. Ruach is the word for soul or spirit in Hebrew. Injichaag means my soul in Anishinaabemowin. It is in my soul that I have the power to choose, to desire, and to be angry. Ive chosen to write my story.

A copy of my family tree lit up in my hands. Old records, dating back to 1834. Records that told of dozens of traditional Anishinaabemowin names. Names that I had never heard and knew nothing about. Now, before my eyes, I could see how many of my Anishinaabe ancestors had a single, distinct, given name. No first or last names. No first and last!

Its been a long, long time. 1834. And now, my quest for your given names, mishomisak (ancestors)! Enclosed by your Anishinaabe names and birthrights, I would have transformed into manhood, a named one, like all of you.

Nookomis! Grandmother. Gitchi-Ayaaa. The records show that your maiden name was Megan or Megwan, a feather. It was also Kitchigabwik. Kitchi (great); gabaw (to stand fast); wik (woman). A distinct description of your character and a way of approaching life; for once you decided on a course of action, nothing could deter you. Your name personifies determination; your title predestined the person you would grow up to be. Falling down; each time you got up, you grew stronger.

Nookomis, you met Shibagabaw. Shiba (underneath); gabaw (to stand); aw (the one). He was the one to stand underneath, to provide and protect you. He was the inini (man), and the root word there is nindj (hand). One hand to provide, the other to protect. You were the iskwew (woman), and the word is taken from ishkode (fire). Fire symbolizes life, and you were the life giver. Inini then tends the fire. Gender balance, partners, harmony, equality.

I honour your generation, Nookomis Kitchigabwik! I roll back the birchbark years to see your glory and knowledge, wisdom and vision.

Its been a long, long time.

I remember your brother, Menawegishig. Me (he whose); nawe (good voice); gishig (sky). He gave your skies good voice, all his life. I benefit from his prayers still today. I remember how much trouble he had walking. Hed slowly unpack his hunting rifle, a .30-30 Winchester, ornate and polished, whispering blessings, moose prayers. He was going moose hunting in the evening. One last push of the cleaning rod into the rifle bore, and off we went, bent with anticipation. We knew. It was as if the moose was waiting for us, his muscles rippling in the dusk as he dipped his head in the water. One last dip, and Menawegishig aimed, fired, and the moose gave his life to us. Menawegishig, as was his custom, divided the meat, and gave each family their helping. Although he was disabled, he provided like any hunter of his generation. He was Menawegishig!

Ill never forget your sister, Wemboma. Wem (she whose); boma (voice wakens). She was there with us at the hunt. She, Wemboma, wakened Menawegishigs prayers so that the moose could be prepared. She had lived many winters. Bibooniwesi. Biboon (winter); iwesi (way of life). Her smile and her deeper tan of springtime proclaimed renewal. She was laughter.

I can still hear your laughter, Wemboma. You always had a tin of snuff or chewing tobacco by your side. There abides my memory! The culture of traditional names has been still, silent, but your voice has awakened me.

Our names have been silenced since 1921, when names like John, Michel, Theresa, Sam, Sarah, David, Mary, Elizabeth, and Peter emerged among my own Shebagabow family. A change was coming to our homeland with the changing of names, a changing of titles and then interrupted promise. Our ancestors had a word that spoke to that promise: nakodamowin. You would nakodam (consent) to what the grandmothers asked you to do for the community. You were appreciated, nookomisak, the grandmothers knew your deep, inner desire for a secure community.

I never knew all my Shebagabow uncles and aunts. Some left too early to give me cousins. But they had promise, potential, and they consented, even with their interrupted lives.

John Shebagabow, I never hugged you. In your short life, you were an Anishinaabe with a Hebrew name. John. Meaning the grace of the Lord. Uncle John, if I were there, if I had the honour, I would name you Zhawendji gogishig, Mercy from the Sky. A mediator. A diplomat. A partner.

Wherever you wander on earth, the sky reminds you to respect the confidences of your Anishinaabeg nation.

And Michel, a Hebrew name denoting a gift from God. In French, its for he who is like God. Michel, you were excited by the changes in our community; the strange traditions of ringing church bells. The pace of your soul was moved by a sense of adventure. A visionary. A friend of freedom. Uncle Michel, if I were there, if I had the honour, I would name you Pagidini gishig. Gift from the First Sky. Adventurer. But your short life crushed your desires. The pace of your community expired, and with it your promise.

And Theresa, an Anishinaabekwe with a Greek name, meaning to harvest. A reaper. An inspiration. Even when you were too young, you gathered ideas on spiritual matters. But you were not given a life of service. Dedication died. Truth and justice cried. Aunt Theresa, if I were there, if I had the honour, I would name you Mamaa winok. Harvest Woman Leader. Dedicated one. But your desires were buried with you.