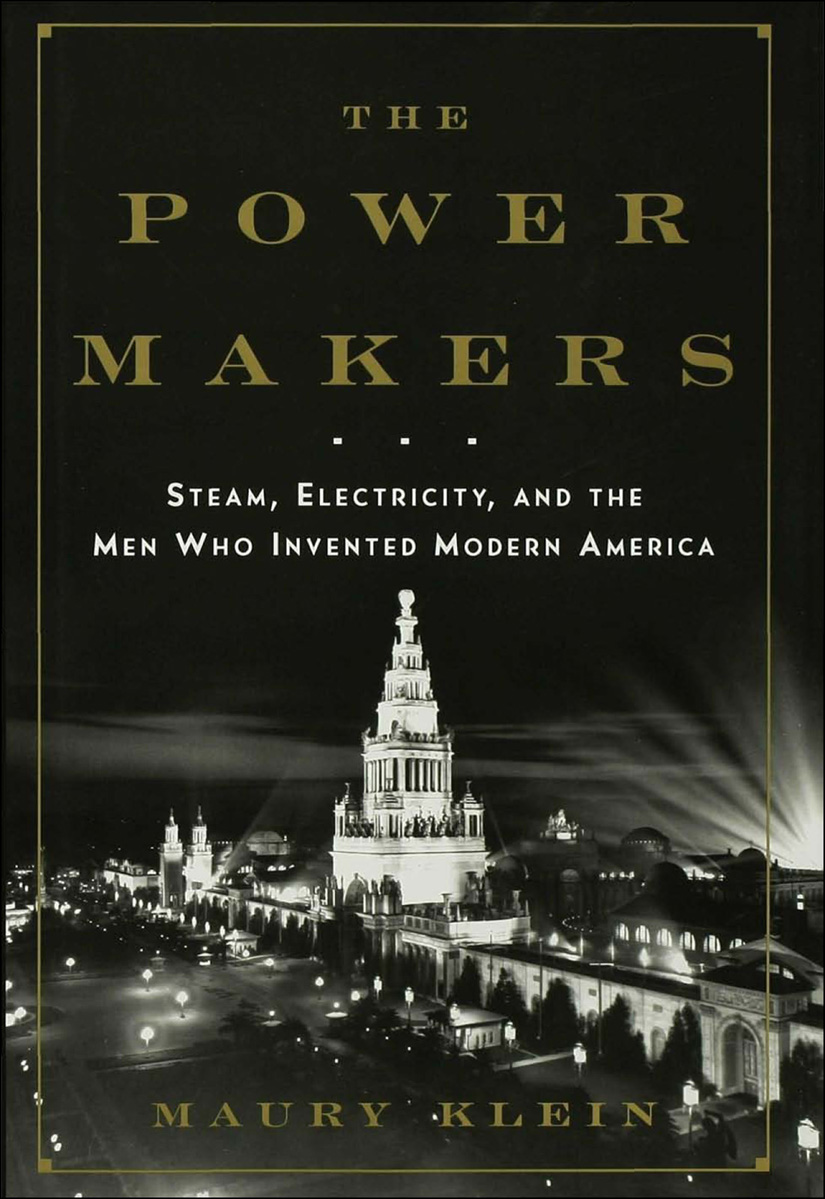

THE

POWER

MAKERS

STEAM, ELECTRICITY, AND

THE MEN WHO INVENTED

MODERN AMERICA

MAURY KLEIN

BLOOMSBURY PRESS

NEW YORK BERLIN LONDON

For Kim, with love and thanks

Contents

THE WRITING OF this book would not have been possible without the help of several people who lent their time and talent to assist my work. The library staff at the University of Rhode Island has once again been unfailingly helpful in obtaining resource materials. I am especially indebted to Emily Greene, who fielded an endless flow of requests with aplomb and dispatch. Sandy Sheldon and Mary Anne Sumner also did everything they could to expedite my work.

Paul Israel generously shared his vast expertise on Thomas A. Edison and helped me find my way through the Edison papers online. Bob Dischner at National Grid provided me with copies of the Tesla letters and other materials housed in the archives of his company. Jill Jonnes graciously answered several inquiries about sources used for her book. Harold C. Platt introduced me to one of his favorite Chicago restaurants and an excellent evening of discussion on Samuel Insull and things electric. Kathy Young could not have been more helpful in providing me access to and copies of materials from the Insull papers housed in the archives of Loyola University of Chicago. My colleague Steven Kay, an electrical engineer, read chapter 4 for technical bloopers, and Richard John kindly read the portion of chapter 5 dealing with the telegraph and furnished me a draft of his work on Morses contribution. To all of these people I am deeply grateful. For any remaining errors, the buck stops with me.

Three other people deserve special mention. My editor, Peter Ginna, maintained steadfast faith in this project through all its twists and turns and provided invaluable feedback once the manuscript reached his hands. So too did my agent, Marian Young, offer constant and needed encouragement on this project as she has on so many others. Finally, my wife, Kim, sustained me through a long project and endured my often prolonged mental and physical absences with good humor and patience.

IT IS CURIOUS that no one has put together a history of both the steam and electric revolutions. Numerous authors have written about the history of electricity or some aspect of it. A lesser number have done the same for steam power, but no one has combined the two into a single narrative. Yet they are inseparable stories at the most basic level. Electricity is the single most important technology of the twentieth century. Without it the modern world simply doesnt exist. People get at least a partial sense of this fact every time the power goes out for any length of time. However, there is a corollary that very few people realize: Without the steam engine there would be no electricity. Together they form the foundation of the modern world.

Industrialization created the modern world. It began during the eighteenth century when certain countries began increasingly to organize their economies around the manufacture of goods rather than agriculture, and to increase their productivity through the use of machinery. This transformation could not have occurred without the most basic revolution of all, the development of new sources of powerespecially the steam engine and electricity. So far has this revolution advanced that today we would be utterly helpless without these sources of power.

Industrialization made the United States and the power revolution made industrialization. Similarly, technology made the electrical revolution and electricity made the technological revolution. The story of how this came about is the subject of this book. It can be fully understood only when both the steam and electricity revolutions are linked together. Theirs is an epic saga, a big-cast show filled with a variety of stars as well as supporting actors. The story involves dogged quests not only to develop startling new machines but also to explain some of sciences most tantalizing mysteries: the nature of heat, light, magnetism, and electricity. In every sense the power revolution was a journey of discovery for all its players. During the story of that journey the spotlight falls sometimes on the players and occasionally on the machines themselves.

When this quest began, no one understood what heat was, or light, magnetism, and electricity. Nor did human beings have at their disposal any source of power greater than human or animal muscle, wind, water, and fire. The curious minds that explored these complex questions happened upon some of the most important scientific principles yet formulated. Their concepts, and the uses to which they were put by others, shaped our modern view of nature and its inner workings. However, they were not alone in their quest. Quite another type of explorer, the inventor blessed (or cursed) with a curiosity all his own, tinkered with the creation of new types of machines despite having only a rudimentary knowledge of the principles that underlay their workings. Gradually the paths of these two parties of explorers began to converge until by the mid-to late nineteenth century their work began at last to move in tandem. By then both the scientist and the inventor had mostly advanced from gifted amateurs to trained professionals who knew how to build on each others insights.

There is another dimension to the power revolution that often gets overlooked. It required not only scientists, inventors, and engineers but entrepreneurs as well. No invention, however ingenious, could be worthwhile unless someone found a way to make it useful and productive. It had to serve some purpose, which means someone had to make a successful business of it. Inventors soon learned that their creations had to be commercially viable, and they were seldom good businessmen. Some, like James Watt, were lucky enough to find the perfect business partner with those talents lacking in themselves; others were not so fortunate and saw their careers flicker out in the bitter embers of what might have been. Even those who possessed both talents, most notably Thomas A. Edison and George Westinghouse, found themselves ultimately outmaneuvered in the business arena.

The story of the power revolution offers more than an interpretation of the origins of industrial America. It suggests another insight into the most elusive riddle of all: What is an American? Most answers to that question emphasize spiritual and intangible ideals and values such as liberty, freedom, rugged individualism, democracy, and religious purpose. However, one major American historian, David M. Potter, pointed to a much more material source: American abundance.

Material abundance has always been present and even dominant in American life. But industrialization developed its potential to startling dimensions of productivity. A century ago Herbert Croly described the promise of American life as one of comfort and prosperity for an ever increasing majority of good Americans... The general belief still is this: that Americans are not destined to renounce but to enjoy. Industrialization fulfilled that promise on a fabu-xii lous scale, thanks to its outpouring of material goods. Even more, it defined the American Dream more vigorously than ever before in material terms until increasingly material things became an end in themselves rather than a means to some larger end.