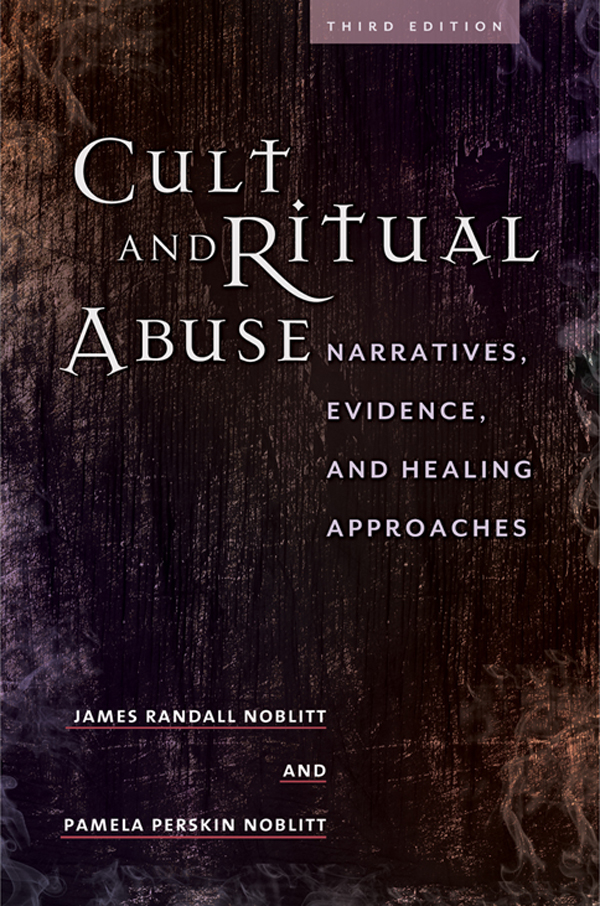

JAMES RANDALL NOBLITT, PhD, is a licensed clinical psychologist in the state of Texas and professor of clinical psychology at the California School of Professional Psychology at Alliant International University. His doctorate in clinical psychology was earned at the University of North Texas while on an Air Force Institute of Technology scholarship. He is formerly a member of the board of trustees of the Texas Psychological Association and with Pamela Noblitt authored Cult and Ritual Abuse and edited Ritual Abuse in the 21st Century. Individually and together, they have also published professional articles regarding topics that include dissociation, ritual abuse, and disability. One of their recent journal articles is Social Security Disability Criteria and Substance Abuse and appeared in the APA journal Professional Psychology: Research and Practice.

PAMELA PERSKIN NOBLITT is a victims advocate and Social Security Disability claimants representative. Formerly the executive director of the International Council on Cultism and Ritual Trauma, she was recognized as one of Eckerds 100 Women of 2000 at the Eckerds Salute to Women in Washington, D.C., on September 20, 2000. She serves on the board of directors of The Human Lactation Center and Hope for Children Foundation.

309.82 CULT AND RITUAL TRAUMA DISORDER

D IAGNOSTIC F EATURES

The essential feature of cult and ritual trauma disorder is clinically significant distress or functional impairment with either (1) disturbing or intrusive recollections of abuse or (2) the presence of involuntary dissociated mental states, either or both of which are the result of ritual (circumscribed or ceremonial) abuse. Dissociated mental states may take the form of unwanted or intrusive dissociated alter identities, trance states, automatisms, catalepsy, stupor, or coma or coma-like states. These dissociated mental states may appear in a spontaneous manner, or they may be triggered by particular stimuli or cues or by the individuals experience of distress.

Ritual abuse consists of traumatizing procedures that are conducted in a circumscribed or ceremonial manner. Such abuse may include the actual or simulated killing or mutilation of an animal; the actual or simulated killing or mutilation of a person; forced ingestion of real or simulated human body fluids, excrement, or flesh; forced sexual activity; as well as acts involving severe physical pain or humiliation. Frequently, these abusive experiences employ real or staged features of deviant occult or religious practices, but this is not always the case. Some reports of this phenomenon indicate that the abuse may occur outdoors, in a residence, day care, laboratory or hospital setting as well as other locations. Ritual abuse is often reported in group settings, but sometimes it is perpetrated by an individual.

A SSOCIATED F EATURES AND D ISORDERS

Associated descriptive features and mental disorders. Evidence of psychological trauma is usually present, and many individuals with cult and ritual trauma disorder also exhibit some symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, if not actually meeting the criteria for this diagnosis as well. Intrusive, and often fragmentary, memories of abuse, alternating terror and emotional numbing, nightmares, amnesia, anxiety, panic, flashbacks, phobic avoidance, and signs of increased arousal are often present. These individuals typically report chronic depression, often with cyclical characteristics. Dissociation of identity is a feature of cult and ritual trauma disorder, and dissociative identity disorder or dissociative disorder not otherwise specified are frequently concurrently diagnosed.

Features of borderline personality disorder may also often be exhibited, and occasionally individuals with cult and ritual trauma disorder will also experience brief psychotic episodes, sometimes with auditory or visual hallucinations. More commonly, these individuals experience or act out strong self-destructive urges, including attempted or actual suicide and self-mutilation. Frequently, there is a desire to injure oneself in a manner that produces blood (e.g., I have to see blood). Sometimes the individual will report a desire to taste, touch, or smell their own blood. Chronic and unmodulated anger and sometimes rage alternate with other moods and affects to create the impression that the individual is unpredictable in mood and unable to manage anger. Strong feelings of interpersonal dependency alternate with detached social aloofness. Narcissism and self-hatred are frequently experienced separately and together.

In children (in addition to the ones mentioned earlier) motoric hyperactivity, impulsivity, and problems in attention and concentration are seen at a rate that exceeds the baseline for children without psychiatric disorders.

Associated laboratory findings. Individuals with cult and ritual trauma disorder typically show evidence of psychological trauma and dissociation on psychological testing.

Associated physical examination findings and general medical conditions. There may be scars from self-inflicted injuries or physical abuse. Somatic symptoms with or without objective medical findings typically include headaches, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary complaints, but other reports of physical pain may be present. In some cases, physical pain will not reflect a current injury but will be a psychological component of implicit memories (e.g., body memories) associated with previous abuse. These individuals also frequently show evidence of mild neuropsychological impairment, which, in some cases, may result from a history of head trauma. Others have argued that psychological trauma in childhood may cause mild neuropsychological deficits in some individuals (e.g., van der Kolk, 1987) but further research is needed to clarify this question.

P REVALENCE

The prevalence of cult and ritual trauma disorder is unknown due to a lack of reliable information. The alleged secrecy associated with ritual abuse may make the accurate tabulation of such statistics difficult or impossible.

C OURSE

The clinical course of these individuals is typically chronic with periodic exacerbations and sometimes partial remission of symptoms. Some of these individuals report that they continue to participate in ritual abuse either as a victim, a perpetrator, or both, typically while in a dissociated state.

F AMILIAL P ATTERN

A history of sexual or ritual abuse is frequently reported among family members. In particular, transgenerational victimization is a commonly indicated pattern, consistent with the familial trends associated with non-ritual sexual abuse of children. However, the extent to which ritual abuse is a transgenerational phenomenon is presently unknown. Features of dissociation are also frequently seen in family members.

D IFFERENTIAL D IAGNOSIS

Cult and ritual trauma disorder must be distinguished from delusional disorder and other psychotic disorders where delusional beliefs are account better for the reports of abuse, particularly when it can be demonstrated that the allegations of abuse are false. However, there are also cases where these diagnoses can exist concurrently with cult and ritual trauma disorder, particularly when corroborating evidence of such abuse exists in an individual who is also exhibiting delusional or other psychotic symptoms. Cult and ritual trauma disorder must be distinguished from malingering in situations where there may be forensic or financial gain and from factitious disorder where there may be a maladaptive pattern of help-seeking behavior. The possibility of suggestibility should also be evaluated and ruled out as a possible alternative explanation for the individuals reports of ritual abuse.