Forbidden Faith

The Gnostic Legacy from the Gospels

to The Da Vinci Code

Richard Smoley

Contents

Inevitably an enterprise like this one benefits from the contributions of innumerable people. It would be difficult to list all of those whose written works and personal insights have made it possible to write this book.

Nonetheless, a few names stand out as worthy of special mention, particularly my agent, Giles Anderson, whose support and guidance were essential in helping me navigate the waters of the submissions process, and Eric Brandt, my editor at Harper San Francisco, whose comments and suggestions have proved invaluable in revising the manuscript. I am also obliged to Elizabeth Berg for a fine job of copyediting. In addition, I would like to thank Jay Kinney, John Carey, and John Connolly, whose comments on specific sections of the manuscript helped me avoid a number of errors. Any that remain are, of course, my responsibility and not theirs. And my friend Christopher Bamford has, as usual, been extraordinarily generous in lending me books from his magnificent personal library.

JUNE 2005

Even the name is strange. Gnosis : glancing at it on the page, you may wonder how it is pronounced. (In fact the g is silent, and the o is long.) The meaning of the word is more perplexing still. Some may know that it has to do with the Gnostics or Gnosticism, and that this was a movement dating from the early days of Christianity. A person with some background in religion might add that Gnosticism was a heresya teaching that allegedly distorted Christs doctrineand that it died out in ancient times. Few would be able to say more.

And yet the subject keeps coming up. G. R. S. Mead, a British scholar who published a study of Gnosticism in 1900, could call his work Fragments of a Faith Forgotten , but the faith is not quite as forgotten as it was a hundred years ago. In a world that is restlessly searching for the newest and the fastest and the easiest of everything, the ancient and cryptic teachings of Gnosticism have edged their way onto best-seller lists and into television documentaries and newsmagazines. Recently Time magazine noted, Thousands of Americans follow Gnosticism avidly in New Age publications and actually recreate full-dress spiritual practices from the early texts and other lore. The literary critic Harold Bloom has even gone so far as to say that Gnosticism is at its core the American religion.

Why has this once-forgotten faith regained its allure? Some of it no doubt stems from the persecution it has suffered in its history. During most of Christian history, Gnosticism was forgotten because it was forbidden; to orthodox Christian theologians, it was not only a heresy but the arch-heresy. Such denunciation by the official church might have served as a deterrent in other eras, but today, in our age of self-conscious individualism and revolt against authority, it often has the opposite effect: condemnation endows a movement with glamour.

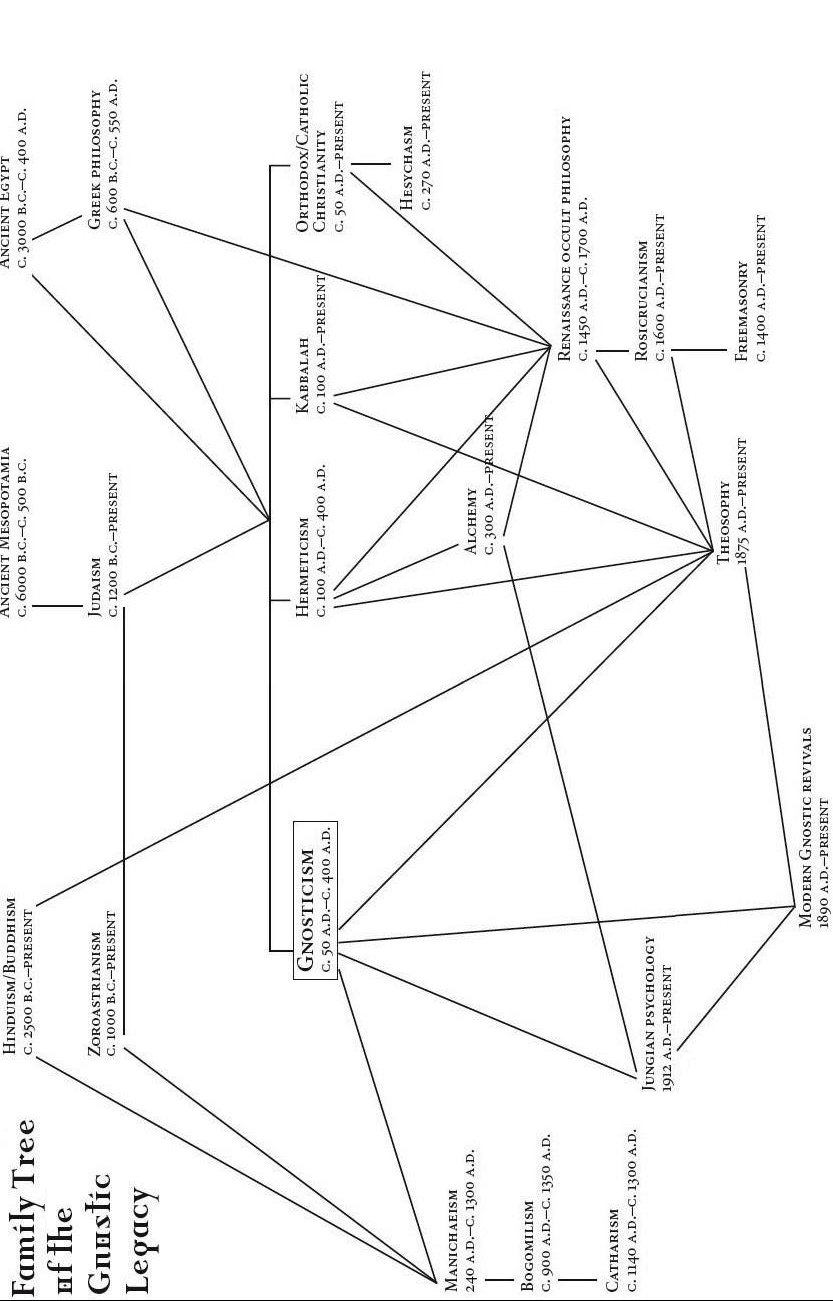

But even this explanation doesnt take us far. You can pick up any history of Christianity and find pages and pages devoted to Ultramontanists, Pelagians, Nestorians, Waldenses, and dozens of other sects and schisms that flourished for a brief time before vanishing into the afterlife of memory. All of them were duly labeled as heresies and duly condemned. Indeed one of the most impressive accomplishments of the Christian church has been the astonishing number of epithets it has devised for groups and individuals who do not see things as the officials do. Of all these dead branches in the family tree of Christianity, why should Gnosticism exercise such a peculiar and powerful fascination?

This isnt an easy question to answer, but the effort is worth making, because it will tell us a great deal not only about Gnosticism itself, but about ourselves and our spiritual aspirations. For the Gnostics to have such appeal, they must offer solutions to problems overlooked by mainstream religion. To see what these are, it would be useful to step back and look at the religious impulse with a wider lens.

Broadly speaking, religion fulfills two main functions in human life. In the first place, its meant to foster religious experience, to enable the individual soul to commune with the divine. In the second place, it serves to cement the structure of society, upholding values and ideals that preserve the common good. The word religion derives from the Latin religare , meaning to bind back or bind together. Religions function is to bind individuals both to God and to one another.

There is no real contradiction between these two purposes; ideally they should work together in perfect harmony. But this rarely happens. More often than not, these two functions conflict in various ways, just as individual needs frequently clash with collective ones. One problem arises when an individual has some kind of spiritual experience that doesnt fit with accepted theology. This person poses an apparent threat to the established order, which regards him with suspicion and at times with hostility. He becomes a heretic and an outcast. If he has some personal charismaand spiritual experience can endow a person with precisely this sort of charismahe may start a church or a movement of his own. Thus are new religions born.

Whether or not this happens, someone with access to an inner source of spiritual insight does not need the churchor does not need it as ordinary people do. Furthermore, such a person often has an inner authority lacking in many leaders of established religions. This was precisely the response Jesus evoked when he began to preach: And they were astonished at his doctrine: for he taught them as one that had authority and not as the scribes (Mark 1:22). Naturally, the scribesthose with a purely external knowledge of religionare bound to regard this person as a threat to their own power.

Of course the scribes see things differently. They view themselves as guardians of the social order. They say that society needs to have consistent patterns of belief and practice as a way of reinforcing common values. A person with an individual and independent experience of the divine threatens (or is believed to threaten) these values. If the religious authorities have some measure of secular poweras they did in Christs time and in the Middle Agesthe mystic will be persecuted or put to death. If the authorities have little secular poweras they do todaythey will have to content themselves with condemning or at least criticizing him.

Its probably unwise to indulge in too much tongue-clicking over this situation; as usually happens, people end up acting mostly as the logic of their circumstances dictates. The spiritual visionary may say, with Luther, Here I stand: I can do no other, but the authorities on the other side of the bench could no doubt say much the same thing. They have the task of supporting and strengthening the faith of the majority, of helping them pass through the ordeals of births and deaths and marriages. They can see that most people are not interested in the subtleties of religious experience and would rather ignore them. Besides, as the clergy have long since learned, many supposedly mystical revelations are little more than symptoms of mental disorder.

Consequently, religious authorities tend to downplay or discourage such experiences; they are too troublesome and unmanageable. Take, for example, the numerous apparitions of the Virgin Mary. Many of theseat Lourdes, Fatima, Medjugorje, for examplewere greeted with hostility by the local clergy, who doubted the good faith of the visionaries and also feared the challenge to their own authority. After all, people are apt to say, if the priests are so holy, why didnt the Virgin appear to them? Only later, if at all, did the church grudgingly accept the legitimacy of these visions.