YOUVE GOT TO TELL THEM

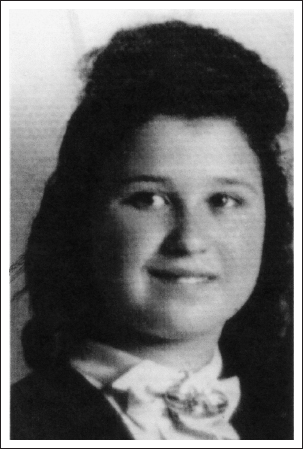

Ida Grinspan, at twelve years old, before

her deportation to Auschwitz

A French Girls Experience of Auschwitz and After

YOUVE

GOT

TO TELL

THEM

IDA GRINSPAN and

BERTRAND POIROT-DELPECH

Translated by Charles B. Potter

LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS BATON ROUGE

Publication of this English-language edition is made possible by an anonymous donation made through the Baton Rouge Area Foundation

Ida Grinspan and Bertrand Poirot-Delpech, Jai pas pleur

Copyright 2002 by ditions Robert Laffont

Preface and afterword copyright 2003 by ditions Pocket Jeunesse, dpartement dUnivers Poche

English edition copyright 2018 by Louisiana State University Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing

Frontispiece courtesy Ida Grinspan.

Designer: Barbara Neely Bourgoyne

Typeface: Fournier Pro

Printer and binder: Sheridan Books

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Grinspan, Ida, 1929author. | Poirot-Delpech, Bertrand, author.

Title: Youve got to tell them : a French girls experience of Auschwitz and after / Ida Grinspan and Bertrand Poirot-Delpech ; translated by Charles B. Potter.

Other titles: Jai pas pleur?e. English

Description: Baton Rouge : Louisiana State University Press, 2018. | Copyright 2002 by ?Editions Robert Laffont; preface and afterword copyright 2003 by ?Editions Pocket Jeunesse, d?epartement dUnivers Poche. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018001498| ISBN 9780807169803 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780807169797 (pdf) | ISBN 9780807169810 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Grinspan, Ida, 1929Childhood and youth. | Jewish children in the HolocaustFranceBiography. | Holocaust, Jewish (19391945)FrancePersonal narratives. | Auschwitz (Concentration camp)

Classification: LCC DS135.F9 G7513 2018 | DDC 940.53/18092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018001498

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

For my parents

murdered at Auschwitz

For my daughter Sophie

IDA

The secret of Hope

is the secret of brotherhood.

GENEVIVE DE GAULLE-ANTHONIOZ

CONTENTS

FRENCH PUBLISHERS PREFACE

Fourteen years old, still a child, already an adolescent. Ida is in hiding deep in the Poitou countryside. The war is not over in the opening days of 1944, but the news is good. Ida can allow herself to hope that she will slip through the net.

Then comes her arrest by the French police, suddenly and unprovoked. Auschwitz, two endless winters. The struggle for survival, with glimmers of hope in the depths of hell.

Impossible to say the unspeakable with words. You Have to Tell Them, beyond being the account of one persons experience, continually asks the same question: How could human beings, German soldiers, French police, act as accomplices, out of fear or out of blindness, of the killing machine that the Nazi regime had become?

How to survive the camp, how to have the strength to bear witness to what happened there, how to overcome the urge to forget in order to fulfill the sacred mission bestowed upon Ida by her companions on the road to death:

If you get back, youve got to tell them. They wont believe you, but youve got to tell them.

FOREWORD

We met in March 1988, at Auschwitz. It was the first time that Ida had returned to the camp since her liberation in 1945. She made herself do it in order to be able to testify to a class of high school students from the Paris region. Bertrand had joined the travel group, which he was going to write about in Le Monde.

We saw each other again often, during ceremonies or gatherings connected with memory. In April 2001, news received from the Polish nurse who had saved Idas life in the infirmary at Neustadt brought us a little closer together. Wanda is alive! Ida called to say. Bertrand immediately remembered this name that Ida had mentioned several times during her 1988 visit to the camp. As Fate had it, only a few hours kept the former girl with frozen feet from seeing once again the woman who saved her life: Wanda Ossowska died in Warsaw at the age of eighty-nine.

This missed rendezvous with reconnection reminded Ida how time works to thwart memory. At age seventy-two, wasnt it time to put down in black on white the testimony that she had been scattering in front of classes of school kids, lest all that remained were vanishing traces? She was perfectly capable of setting down her memories, she whom Madame Picard, her teacher from the Deux-Svres, considered as we shall soon see as her best student in French. But she would feel less intimidated by the writing of it if only...

Bertrand volunteered to be the scribe of this work for four hands that Nicole Latts decided to publish at Robert Laffont. The deal was sealed in 2001, with the intense serenity that such shared conceptions inspire. The story would be Idas, it would have her face, her voice, as she had indeed lived it in the flesh. Bertrand would have the role of narrator, to recall contemporary events, and to express those things that emotion or humility might prevent Ida from stating on her own.

Thanks to being born French Catholics, neither Bertrand nor his family had had to suffer directly from the war waged by the Nazis and their accomplices on a little Jewish girl of fourteen, all the way to the distant reaches of a farm in the Poitou. He had felt something akin to scandal and shame over his sheltered adolescence when a friend, Youra Riskin, disappeared from his class in school in June of 1943; and then there were the trials of the Shoah Barbie, Touvier, and Papon which he had followed in the hope of better understanding, of honoring, of transmitting.

What you are about to read had the strange effect of uniting us as brother and sister. We were both born in 1929! Let us say that this coincidence worked out well for us, while at the same time not wanting to make too much of a connection that arises, like the subject of our mingled sentences, from the unspeakable.

IDA AND BERTRAND

YOUVE GOT TO TELL THEM

PART I

The Jewess of Li

The Sound of a Motor in the Night

It is after midnight, January 31, 1944, when a Traction Avant in Poitou. Behind the solid wall, a young girl wakes up suddenly. None of the neighbors would be venturing out to this place at such an hour.

It can only be for me! fourteen-year-old Ida Fensterzab says to herself, not yet realizing that she has just entered the point of focus of one of the greatest outrages in human history...

A victorious army, though on the point of being beaten, that still can find nothing more urgent to do than to press its subjects to go and round up a little Jewish girl from the Deux-Svres in order to send her to hell in Auschwitz! The Homeland of the Arts waging a war to the death against a child, among thousands of others, for the crime of simply having been born!... The circumstance is so atrocious, so unimaginable, that one ends up not imagining it at all, no lightning bolts from the sky, no Wagnerian racket, without even a chorus of mourners.

But barbarity enters on tiptoes Idas first lesson from what she will live through on this winter night, in a hamlet where everything seemed to promise the peaceful slumber of places forgotten by History. It is through the random chance of thwarted precaution that supreme inhumanity thrust its head in, behind the faces of policemen whom one wants to believe to be good and pious fathers, despite their staggering lack of any spontaneous sense of pity, and without showing any other sign of the monstrousness of what they were up to for they did let on that they knew what the future held in store than a big checkered bandana pulled out to wipe a sweating brow, as a sign of embarrassment. Thus tragedies are born quietly, on the sly: when will we understand that? Always too late?

Next page