Contents

Guide

M ICHAEL K ORDA

Passing

A Memoir of Love and Death

For Margaret, always

We rarely go gentle into that good night.

SHERWIN B. NULAND , How We Die

PART I

Ive known that something was wrong for a long time.

Y OU DONT KNOW what youve got until its gone, my wife Margaret was fond of saying, meaning that you shouldnt take the good things of your life for granted.

When you see something you want, go for it, was also one of her maximsshe was never one for dithering or shilly-shallying, as she put it. Hesitation was not part of her makeup, big life decisions or small ones alike she made quickly, without looking back, or regret afterward.

I was the more cautious one, inclined to think things out, or through. Look before you leap, might have been my motto, a note of caution that was washed away by the fact that from the first moment I set eyes on Margaret I knew she was the woman I had always wanted. It was love at first sightsurely the most dangerous of emotionsand as I was shortly to discover it was mutual.

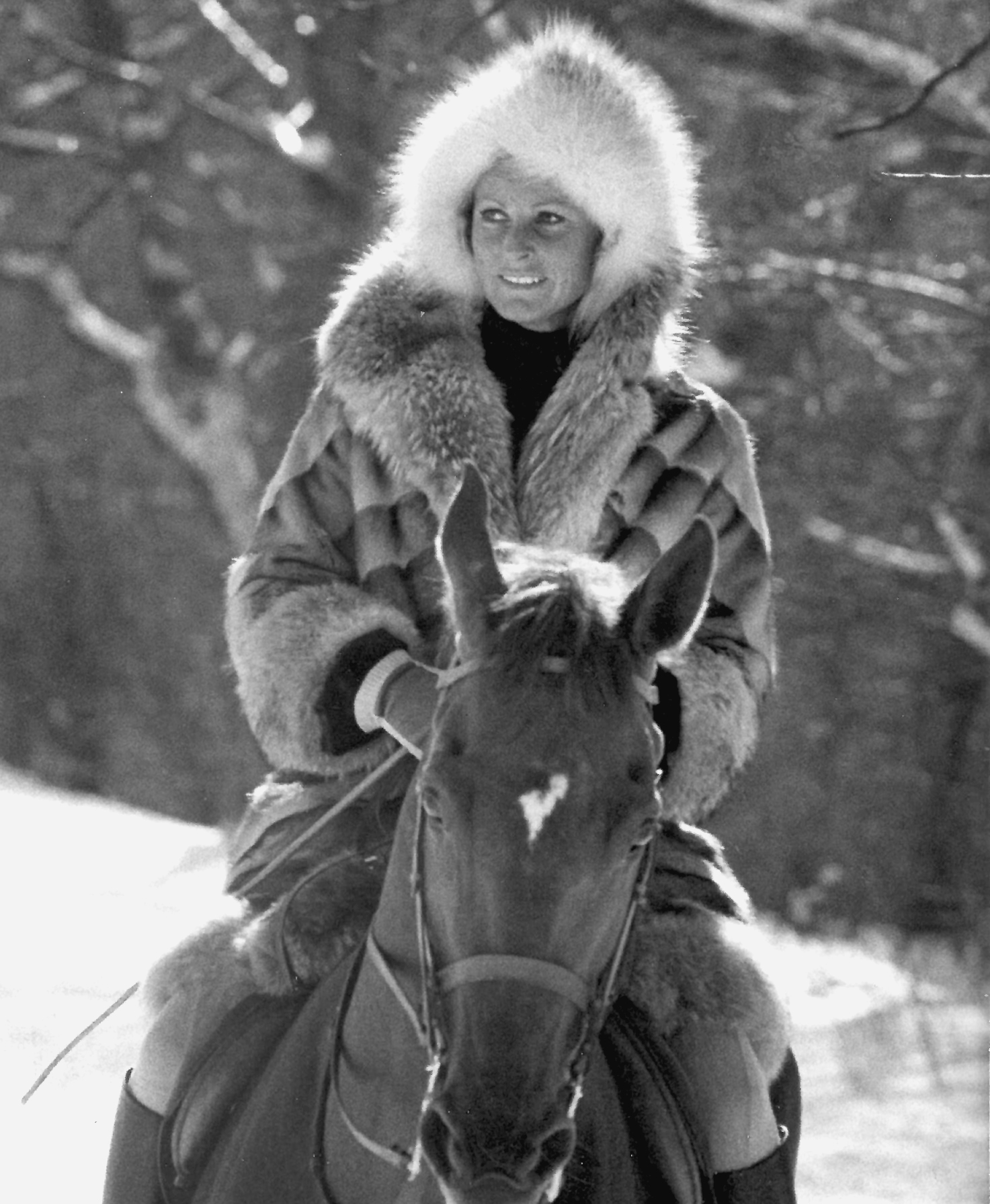

We met in 1972, of all improbably romantic ways while riding in New Yorks Central Park. I used to board a horse then at the one remaining stable near the park on West Eighty-Ninth Street and rode early every morning before taking the subway downtown to work. Margaret, a much more gifted and experienced rider, had started to rent a school horse in the mornings. Our rides were not synchronized, so for some days we went around the reservoir on the bridle path in different directions, merely saying good morning politely as we passed each other.

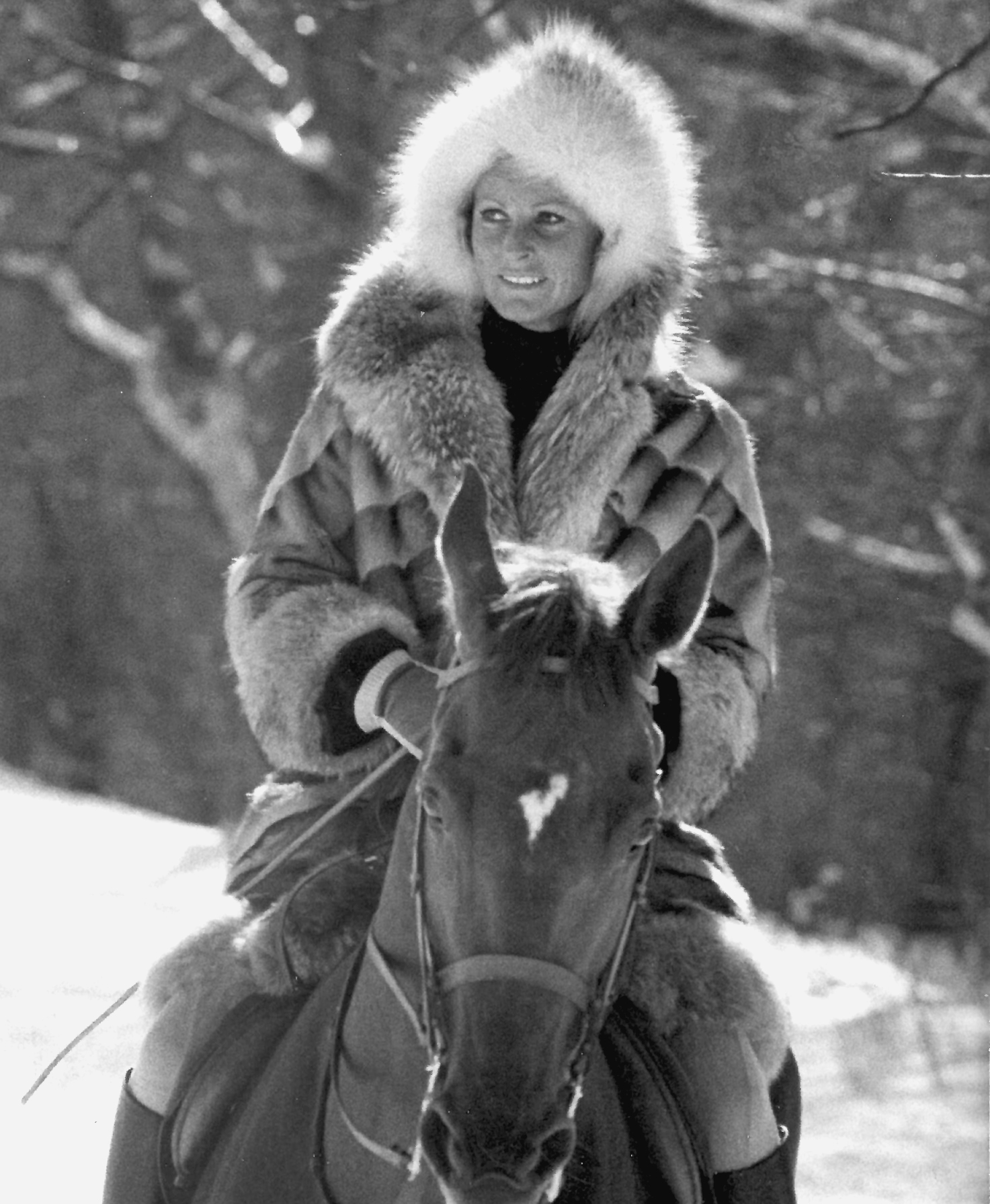

It was midwinter, so we had the bridle path pretty much to ourselves. The few riders who braved the weather went out in bulky down parkas suitable for a polar expedition; Margaret wore a sealskin coat with a silver fox collar, her long blond hair tucked up under a towering white fur cap, looking like Julie Christie in Doctor Zhivago. I soon learned she was married to Magnum photographer Burt Glinn, and not surprisingly that she was a model. I was married too. I could tell that this was going to be complicated, the mutual attraction was too strong for it to be otherwise, and soon we were riding around the reservoir side by side in the same direction, and stopping for a cup of coffee on the way to the B train.

By the spring we knew, or thought we knew, everything there was to know about each other, until one day when instead of stopping for a cup of coffee on Eighty-Sixth Street and Broadway, Margaret asked if I would like a cup of coffee in her apartment on Central Park West and I said yes, both of us knowing that the relationship was about to get even more complicated. Burtby then my wife and I had become friends with the Glinns and we often went out to dinner togetherwas away photographing in Indonesia or somewhere, we had the apartment to ourselves. We forgot about the coffee, Margaret put Carly Simons album No Secrets on, Youre So Vain was the big hit of 1972, and we went into the bedroom and embraced passionately, just as I had been imagining for so long, at which point it became apparent that Margaret had left the Vuitton bag that accompanied her around the world in her locker at the stable, and with it her bootjack. We fell on the bed, and Margaret said, Weve got to get our boots off.

In those days I still had a pair of riding boots made for me in London by Henry Maxwell on Jermyn Street, tight enough that I needed to sprinkle talcum powder on the calves of my breeches before using boot pulls to haul them on, and Margarets were, if anything, tighter. (English riding boots are supposed to fit like a second skin.) I told her to hold on hard to the headboard of the bed, got down on both knees, removed her spurs, and began to pull as hard as I could, to no effect. Without a bootjack there seemed no hope of getting them off. I stood up, she raised one leg, and I pulled harder. I could cut them off, I suggested, but Margaret shook her head; she did not want to ruin a good pair of riding boots. From time to time Margaret lost her grip on the headboard and slipped to the floor, but after what seemed like hours I managed to get one of her boots off, then the second one popped off unexpectedly and I landed on the floor with a thump.

We both broke into laughter at the sight of ourselves in the mirror. I looked at my own boots. To hell with the bedspread, Margaret said, and so we made love for the first time, Margaret in her riding breeches and me in my boots, and never looked back. For the next forty-five years we were each others lover, companion, and best friend.

Margaret seemed invulnerable, her beauty and her athleticism untouched by age, her presence at once commanding, reserved, and slyly appealing, seemingly invulnerable. Even into her sixties she could still wear a bikini and look good in it, walk an hour a day in any weather, ride competitively and winas a horsewoman she won the last of her five national championships at the age of sixty-six. She had never experienced a serious illness or any kind of surgery, not even the removal of her tonsils or her appendix, until 2011, when she had a melanoma removed from her right cheek, a scary moment, but one she managed to change into a kind of party, with friends coming from all over to sit and wait for her at New YorkPresbyterian Hospital as the procedure was done under local anesthesia in the doctors office while she was fully dressed, including her favorite pair of cowboy boots.

Unlike most people born in England, Margaret had perfect teeth despite a lifetime of drinking tea and eating too many sweets, especially her favorites, Cadbury Fruit & Nut chocolate and Kit Kat bars. Age had weathered but not diminished Margarets looks and sharpened the dramatic curve of the cheekbones; by 2016, she retained the agility of a young person and the perfect posture of the fashion model she once had been, she could still command attention when she entered a room. A lifetime spent outdoorsshe could not bear being cooped up indoors during the daylight hourshad given her a kind of permanent tan. I was the one who had the big medical dramas over the years, two cancer surgeries and a cardiac arrest, while she remained virtually unscathed at the age of seventy-nine.

Nothing had therefore prepared us for the fact that we were standing outside a nondescript medical building in Poughkeepsie on April 1, 2016, of all dates, having just been told that Margaret had a large malignant brain tumor that might kill her in a matter of weeks if it wasnt taken care of at once.

The first step, the doctor told us, was to perform a biopsy of the tumor to find out what he was dealing with, and he could do the procedure the day after nextthere was no time to waste. It was no big deal, he assured us, he would merely drill a small hole in the skull and take a tissue sample, then we would know exactly what we were facing.

I said that drilling a hole in the skull sounded like a pretty big deal to me, but that fell upon deaf ears. He was determined that we should realize the urgency of the matter, he told his secretary to give us an appointment card and a thick sheaf of forms to fill out, and dismissed us. We should read and sign everything before he saw us again on Friday.