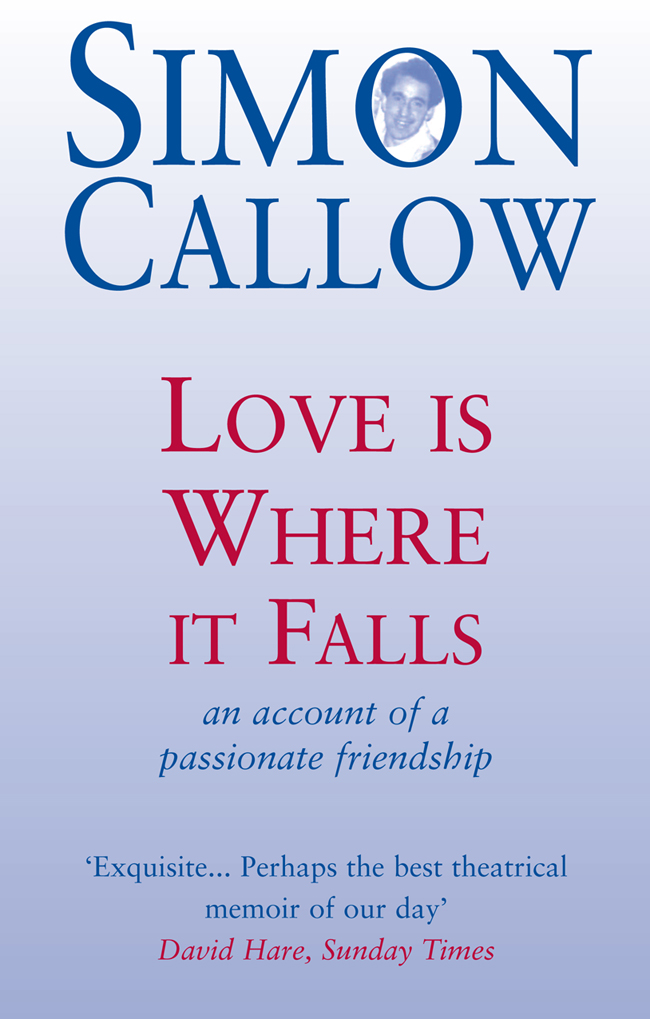

Simon Callow

Love is

Where it Falls

An Account of a Passionate Friendship

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

We have not begun to live

until we conceive of life as a tragedy

William Butler Yeats

This book is dedicated to J., B. and M.,

in the name of love

Contents

And he went back to meet the fox.

Goodbye, he said.

Goodbye, said the fox. And now here is my secret, a very simple secret: it is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.

What is essential is invisible to the eye, the little prince repeated, so that he would be sure to remember.

It is the time you have wasted for your rose that makes your rose so important.

It is the time I have wasted for my rose said the little prince, so that he would be sure to remember.

Men have forgotten this truth, said the fox. But you must not forget it. You become responsible, forever, for what you have tamed. You are responsible for your rose...

I am responsible for my rose, the little prince repeated, so that he would be sure to remember.

From The Little Prince

by Antoine de St-Exupry

translated by Katharine Woods

Nothing I have written has been more directly personal than the present book. It passed through many drafts before reaching its final form, and in order to achieve anything like an objective view of it, friends a small army of them have been bombarded with successive versions. Their reactions have played a crucial part in shaping the book, and I thank them all deeply, with particular gratitude to David Hare, Martin Sherman, Peter Gaitens, Angus Mackay and Ann Mitchell. I should also like to thank Nick Hern, editor, publisher and friend, for equal quantities of patience, encouragement and perception during the books seemingly interminable evolution, and Maggie Hanbury, my agent, for her entirely correct conviction at a crucial point that there was a ways yet to go.

S.C.

Part One

Somewhere in a safe in a room in a solicitors office in London is a small urn, containing the ashes of a remarkable woman: Peggy Ramsay, the most famous play agent of her time. It is nearly seven years since she died, and I have still not summoned up the courage to do what she asked me to do: to take her ashes to the cemetery of San Michele in Venice and scatter them there. Why can I not do this simple thing for her?

*

It was a sunny summers morning in 1980 when for the first time I ascended the spindly staircase, festooned with posters of theatrical triumphs past, that led to Margaret Ramsay Ltd, in Goodwins Court, off St Martins Lane, in the centre of the West End of London. I had come to collect a copy of a play in which I had acted a couple of years before, in the theatre, and which I now hoped to persuade the BBC to do on television. Straight ahead of me, at the top of three flights of stairs, was the door with the agencys name on it, under several layers of murky varnish. The last thing I expected or wanted to do was to talk to Peggy Ramsay herself, but when I opened the door, there she unmistakably was, sitting at a desk or rather on one as she flicked through a script, almost hitting the pages in her impatienceto make them turn quicker. Her skirt was drifting up round the middle of her thighs to reveal knee-high stockings. Hearing me enter, she looked up with an expression which seemed to mingle surprise, amusement and challenge, as if shed been expecting me but had rather doubted Id have the courage to come. It was a curiously sexy look.

Hello, I said, Im

I know exactly who you are, dear, she said. Tell me, she continued, as if resuming a conversation rather than beginning one, do you think Ayckbourn will ever write a really GOOD play?

Its an interesting question, I replied nervously, slightly inhibited by the fact that I was at that moment appearing in a play by the author under discussion, and that he was by far the most successful client of the woman asking the question. Youd better come in, she said, calling over her shoulder for tea and kike to one of the young women in the office, as she ushered me into what was evidently her private office. Adjusting and readjusting her skirt a flowery item, beige, silk and diaphanous she kicked off her shoes and seated herself at her desk, while I settled down on the sofa.

Ah, that sofa... she murmured, mysteriously, with many a nod and a smile, as she absent-mindedly combed her fine golden hair. The room had an air of glamorous chaos about it, half work-place, half boudoir. There were shelves and shelves of scripts right up to the ceiling, their authors names boldly inscribed in red down the spine: in one quick glance I saw Adamov, Bond, Churchill, Hampton, Hare, Rudkin. There were books, in great tottering piles; awards, both framed and in statuette form; posters (all of Orton, Nichols in Flemish, Mortimer onBroadway); plants everywhere, trailing unchecked; discarded knee-high stockings, scarves, hairbrushes, makeup bags, mirrors and hats: huge, wide-brimmed, ribbon-toting hats, four or five of them, draped over the furniture. The air was headily fragrant, confirming the rooms overpoweringly feminine aura.

In the midst of it all was Peggy, clearly the source of both the glamour and the chaos. She was now answering the telephone in a startlingly salty manner. Well, youll just have to tell them to fuck off, dear, she was saying to one caller, I shall tell Merrick that we must HAVE a million to another. But your plays no GOOD, dear, she cried, to a third, informing me in an entirely audible aside Its Bolt; Im telling him his plays no good, then informing him, Ive got Simon Callow here and Im telling him your plays no good. Whatever his response was, it made her chuckle richly. Well it isnt, dear, is it? There were more calls, all rapidly despatched; to my astonishment, she seemed to think that talking to me and, even more surprising, listening to me, was more important than the day-to-day business of running the most successful play agency in the country, perhaps the world. She dismissed that in a phrase. The word agent, she said, is the most disgusting word in the English language.

Names flew about the room, resonant, legendary, as the conversation got under way. She was on, not first but so much more intimate last-name terms with them all: Lean, Ionesco, Miller; nor was she confined to the living, or those whom she might have known personally: Proust, Cocteau, Rilke, were all swept up in the torrent of allusion and anecdote. It was immediately evident that she judged her clients, and herself, by direct comparison with the greatdead. This gave the conversation uncommon breadth; but it was the least of what made the meeting extraordinary.

The overwhelming impression was of the airy, fiery presence of the woman herself. She was never still, not for a second, but there was nothing restless about her. She seemed rather to be performing a moto perpetuo, choreographed by some innovative genius into the physical representation of a dancing mind. Her long-fingered hands fluttered, her hair flew out of control, her slight frame drew itself up and up as if she were preparing for a high dive, then would suddenly flop down till she was almost horizontal in her chair, arms stretched out, legs shockingly wide apart, nether regions barely concealed by whichever small part of her transparent skirt was theoretically supposed to be covering her. Sometimes, to make a point, she would reach for a book or a script, wrap her fist round the arm of her spectacles, then whisk them off, thrusting her face flush up against the page. When shed read what it was she was looking for, shed unceremoniously throw the book or script down and shove her spectacles back onto her face. Even this alarming procedure was somehow gracefully effected.