Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

CONTENTS

For Matt Jones

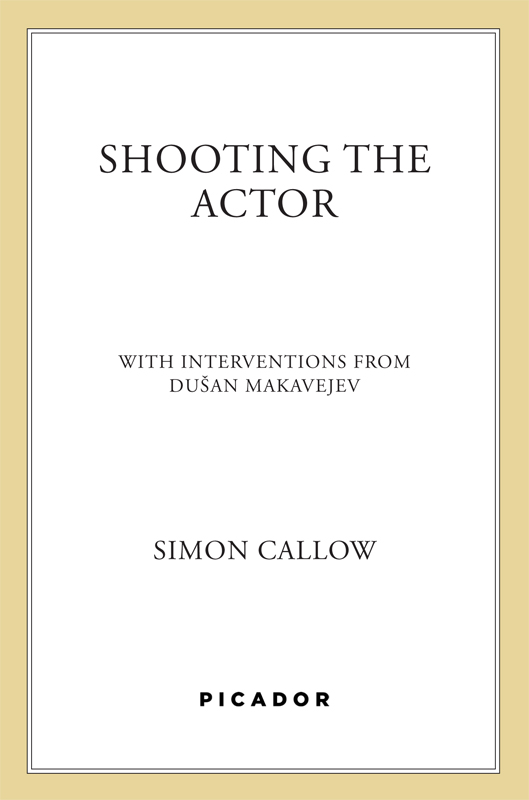

In 1990, my friend and first publisher Nick Hern, who had commissioned Shooting the Actor and was about to publish it, had the worst year of his life. The head of the company with which he had merged his independent outfit succumbed to a form of dementia and started to throw out his colleaguesliterally, onto the street, with their filing cabinets and the rest of their office furniture. Accordingly, when the book appeared, it did so without much help from Nick or the parent organisation. It had a few reviews in obscure publications, and those few reviews were savagely dismissive. A year or two later, Nick relocated his organisation to Random House, where he met Frances Coady, publisher of Vintage Books UK. She read the book enthusiastically, and republished it under her imprint, when it was re-reviewed with some favour. I was very happy about this; I had always liked the book, manic-depressive though it sometimes is, as much because of Duan Makavejevs somewhat dyspeptic contributions as for my own. I believed, and still believe, that it offers an accurate account of what its like for an actor to be involved in a movie. This particular movie was not a happy one for me, but, pace Tolstoy, all movies, happy or unhappy, are happy or unhappy in the same way.

The book has remained in print in Britain to the present day, but when Frances, now head of Picador, suggested publishing the book in America, I seized the opportunity to write a little about some of the other films in which I have appeared, which happens to include some very successful ones. In fact, the book now constitutes a sort of autobiography in film, just as Being an Actor is an autobiography in theatre. The original text of Shooting the Actor the main body of the book, needless to saywill be found in its chronological place, that is, after A Room with a View and before Mr. & Mrs. Bridge. At the end, by way of conclusion, I have added a section called What Its Like, which (as in Being an Actor ) reverses the telescope, focussing on the general rather than my particular experience of acting in film.

If I have omitted a film (and a list of all my films is attached as a sort of index) it is not because its unremarkable in any way, but because I dont believe it adds anything to what Ive learned about acting in movies over the last twenty years of being involved in them. And I havent written at all about the film I directed in 1990, The Ballad of the Sad Caf. Thats another book altogether.

My life in film has been a completely unexpected bonus. I never expected nor particularly desired to work in movies, nor until quite late in my career did anybody seem to think that the movies were crying out for me. I had very little notion of what the process of making a film might be like, despite exposure to movies about movies like Truffauts La Nuit Amricaine, which I took to be as true to life as the film 42nd Street was to putting on a musical in the theatrethat is to say, total fantasy. When, during the late seventies, I was working regularly in television, film was regarded as a completely different activity, film actors a separate breed. The process of making television was not dissimilar to making theatre: there were extensive rehearsals followed by a very brief filming period, in which scenes were mostly shot in sequence.

It was my great friend, the literary agent Peggy Ramsay, who, believing that I should fill this gap in my education, arranged for me and my partner Aziz to visit the set of Quartet, a Merchant Ivory film being shot in Paris in 1980. It was an astonishing experience, and I had to offer my silent apologies to Truffaut: it was La Nuit Amricaine all over again. The location was the legendary nightclub Le Buf Sur le Toit, and the place was swarming with gorgeously clothed people milling about under bright lights. Despite the twenties setting, it was impossible to tell where the film stopped and life began: there were waiters who seemed to be real, silent and weary actors (I caught sight of Maggie Smith in an exquisite beaded cloche, decoratively slumped in a corner) while highly animated other people screamed and rushed around. Makeup was being applied, costumes were being adjusted, microphones were being replaced. I had been told to find the producer Ismail Merchant, and this presented no difficulties: there he unmistakeably was, this immensely handsome, wildly energetic figure in a Nehru jacket and long flowing cotton pants, doling out bowls of curry to the cast and the crew on whom he bestowed seraphic smiles, punctuating this courtly activity with screamed instructions to various functionaries who were clearly failing in their duties. One of these, to whom the most savage outbursts were directed, was a taller, grey-haired man of fastidious demeanour who was calmly rearranging forks at a table in the centre of the restaurant. One phrase of Ismails repeatedly aimed at this man rose above all the hubbub: Shoot, Jim, shoot!! This was evidently James Ivory, the director, who continued arranging forks. When he was good and ready, he murmured something to an assistant and suddenly the cry Shooting! echoed round the four points of the compass like a Monteverdi motet: Shooting!!! Shooting!! Shooting! Shooting. A deep silence fell, a little wave of tension ran through the building, and a great crane with a camera and a cameraman perilously attached to it proceeded to make its way down the room like some elegant dinosaur. Then suddenly the cry: Cut!!! along with its Monteverdian echo: Weve cut!! Weve cut! Weve cut. Again and again and again this was repeated until the problemwhether mechanical or interpretative; it was impossible to tellwas resolved.

It was mightily impressive, but I didnt quite know whether I liked it. It seemed ungraspable. How would one make ones contribution? Alan Bates wandered by. We had been introduced at the National by John Dexter. He said, with a little roll of his eyes, Filming! I said that Id never done any. Oh, he said, that wont last long, will it? After that, I suppose I started to nurture at the very least some curiosity about exploring the new medium. I saw Jim and Ismail again in London with their friend Felicity Kendal, with whom I was still acting in Amadeus, and all the conversation was about the roles that I might play for them. Nothing happened because I was acting on stage more or less continuously. I left the National shortly afterwards and did three plays in swift succession. When I was playing in J. P. Donleavys The Beastly Beatitudes of Balthasar B at the Duke of Yorks Theatre, in the autumn of 1981, Jim and Ismail formally asked me to act in their film Heat and Dust, and for a while it seemed that it might happen, but the playwhich was doing rather shakily at the box officekept getting reprieved and finally they had to cast someone else. This was a setback, not only for my movie career, but also for my mothers. Ismail had phoned me one day when it seemed more rather than less likely that I might be able to do it and said, How is your mother? He had never met her, but I reassured him about the state of her health. Would she like to come to India to be in a film? I need some very elegant older ladies to visit the harem. I assured him that I would enquire, though I never did. If Id never acted in a film, I was damned if she was going to. Sorry, mamma.