G rateful appreciation for their time and trouble to all those people whom I interviewed. My thanks for all contributions to: Sally Baxter; Ann Broadbent; Philip Martin Brown; Simon Callow; Patrick Connor; Dame Judi Dench, DBE, OBE; Julian Fellowes; Barry Foster; Arthur Ibbetson, BSc; Philip Jackson; Saeed Jaffrey, OBE; Tony Jordan; Arthur Lappin; Elizabeth Lloyd; Alan MacNaughtan; Richard Mayne; Kevin Moore; Barry Norman; Daniel OHerlihy; Jenny Passmore; Elizabeth Pursey; Sir David Puttnam; Bruce Robinson; Roshan Seth; Nabil Shaban; Jack Shepherd; John Southworth; Neil Stacy; Janet Stone; Ronald Wilson.

Thanks to John Blake and all at John Blake Publishing.

Life is ladders, thats all.

G UY B ENNETT , A NOTHER C OUNTRY

S lanting shafts of early morning light pierce the dense woodland, glinting off the deadly blade of the curved hunting knife gripped in Nathaniels right hand. He is stripped to the waist, his long unruly black hair bouncing off his muscular shoulders. His breath comes in faint rhythmic pants as he runs swift and sure, crashing through the undergrowth in unison with his blood-brother Uncas.

Nearby, another kind of crashing tells him what he needs to know He sheathes the knife. Smoothly, purposefully, he slides the wooden-handled, long-barrelled rifle from his back and slots it under his arm as the powerful deer breaks cover.

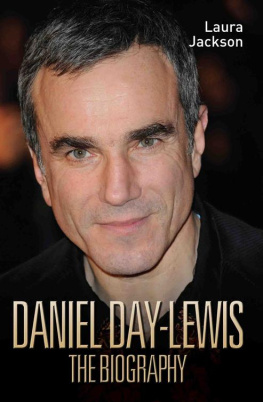

Arrestingly intense eyes set in a strong, unlined face concentrate with deadly intent as he takes aim. Slowly, inexorably, the sleek blue-grey steel barrel moves round in a sweeping arc to stare the viewer straight in the eye. Seconds later he fires. As the fierce flame flashes across the screen, Daniel Day-Lewis blasts his way to Hollywood heart-throb status. The part is frontiersman Hawk-eye; the film is Michael Manns lavish 1992 adaptation of James Fenimore Coopers classic novel TheLast of the Mohicans.

The description, heart-throb, does not sit easily on Daniel Day-Lewis who often questions the validity of being an actor at all. Yet, the following two decades would see him inhabit with raw intensity a string of diverse roles, turning out vivid portrayals of, among others, a tortured soul, a wronged Irishman, a hideously unhinged New York gang leader and a chilling oil prospector before astonishing audiences the world over, in 2012, with a barnstorming performance as one of Americas most revered Presidents, Abraham Lincoln. Daniels immense talent for assuming anothers identity on screen perpetuates the mystery of who this gifted chameleon is in real life.

What is hardly a mystery is why he should have opted for a career in film at all. His maternal grandfather was the legendary film producer Sir Michael Balcon, one of the pioneers of British cinema. He reputedly gave Alfred Hitchcock his first job and was head of Ealing Studios during its most fertile period from the 1930s to the 1960s. He was responsible for turning out such influential comedy classics as Whisky Galore, Kind Hearts and Coronets and The Lavender HillMob. Respected film critic and BBC television presenter Barry Norman defines his importance. Ealing Studios was the best ever, he says, the jewel in the crown of the British film industry, particularly in the war and post-war years, and Michael Balcon was the head of all of that.

Michael Balcons family were Latvian refugees from Riga who had come to England around the turn of the century. The family of his wife, Aileen Leatherman, whom he married in 1924, came from Poland. Their daughter, Jill Angela Henriette Balcon, Daniels mother, became a familiar voice on British radio as a continuity announcer and verse reader during World War II. Later she was famous as one of the countrys star radio actresses.

Daniels grandparents on his fathers side were the Reverend Frank Cecil Day-Lewis, a curate in the Protestant Church of Ireland, and his wife Kathleen Blake Squires. Their only son Cecil became a writer, an Oxford professor and eventually Poet Laureate. Born in what is now County Laois, Cecil had strong roots in Ireland. During the 1930s, when he was briefly a member of the Communist Party, Cecils name became inextricably linked with a clutch of left-wing, anti-fascist poets comprising W.H. Auden, Louis MacNiece and Stephen Spender. Collectively they were often satirically referred to as MacSpaunday.

At this time Cecil was married to Constance Mary King, and during their twenty-three-year marriage they produced two sons, Sean and Nicholas. The marriage ended in divorce early in 1951. By this time Cecil had struck up an association with Jill Balcon, twenty-one years his junior, whom he had met when they were co-readers for the BBC Home Service programme Time for Verse. They married in April 1951 and two years later had their first child, a daughter Lydia Tamasin. It was a further four years before their son was born on 29 April 1957.

Inheriting his mothers jet black hair and startling pale green eyes, Daniel arrived two days after his fathers fifty-third birthday in the front room of the Day-Lewis family home at 96 Campden Hill Road, west London. Cecil immediately penned a poem in celebration of the birth called The Newborn. At the christening at the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields, the baby was baptised Daniel Michael Blake Day-Lewis Daniel as an amalgam of the parents Jewish and Irish associations, and Michael Blake to honour one grandparent from each family, thereby keeping the peace with both.

In keeping with Cecils socialist sympathies, one of Daniels four godparents was Julia Gaitskell, whose father Hugh was the leader of the British Labour Party, then languishing in opposition. Then, like his sister Tamasin before him, baby Daniel was promptly placed in the care of the live-in nanny, Minny Bowler, who became the centre of his day-to-day life.

With the addition of a second child to their family, Cecil and Jill decided to look for a roomier house and found one almost immediately. In its heyday, 6 Crooms Hill in Greenwich, southeast London would have been a fine example of Georgian architecture, nestling snugly at the foot of a sweeping hill, opposite an equally grand, and lively, music hall. By the end of 1957, when Daniel was eight months old, its elegance had faded and the four-storey end house, complete with imposing sash windows and fronted by black wrought-iron railings and gate, was in serious need of renovation. The adjacent music hall was nothing but a derelict eyesore. Nevertheless the family moved out of Campden Hill Road and into Crooms Hill, or rather Cecil and Jill did. Daniel and Tamasin were farmed out to the comfort of Jills parents family home until work on the house was completed.