An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

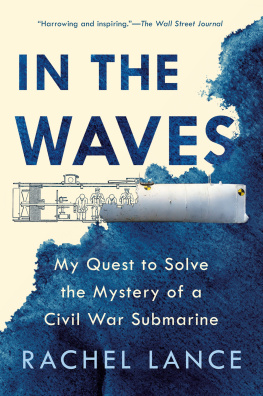

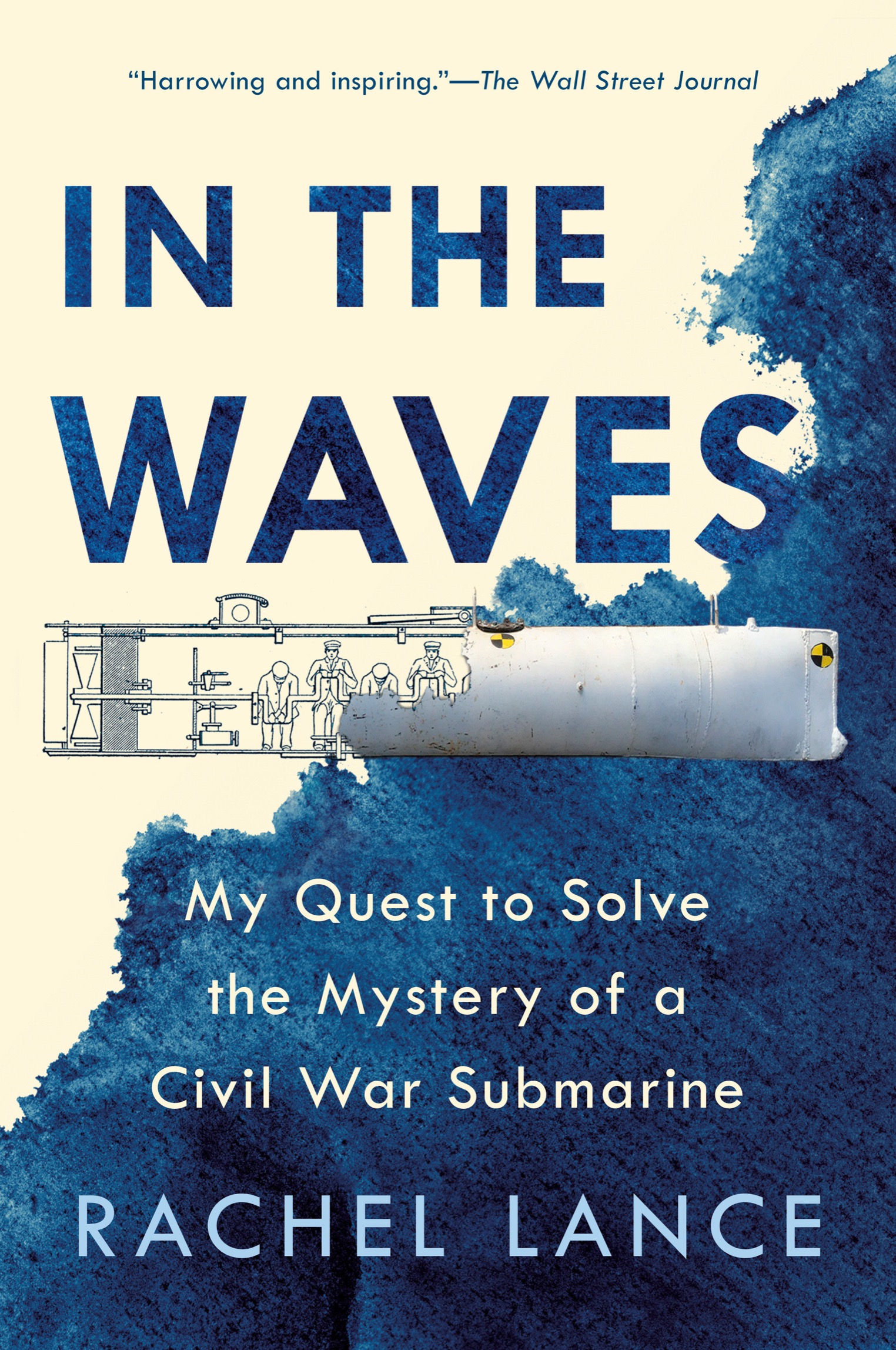

Copyright 2020 by Rachel M. Lance

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

DUTTON and the D colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Permissions appear on and constitutes an extension of the copyright page.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLI CATION DATA

has been applied for.

ISBN 9781524744151 (hardcover)

ISBN 9781524744168 (ebook)

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Cover design by Sarah Oberrender; image of submarine courtesy of the author; interior schematics: Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo

pid_prh_5.5.0_c0_r3

To my brothers Jeff & Kevin,

Because I think we all made each other into engineers

CONTENTS

The Ocean has its silent caves,

Deep, quiet, and alone;

Though there be fury on the waves,

Beneath them there is none.

The awful spirits of the deep

Hold their communion there;

And there are those for whom we weep,

The young, the bright, the fair.

Calmly the wearied seamen rest

Beneath their own blue sea.

The ocean solitudes are blest,

For there is purity.

The earth has guilt, the earth has care,

Unquiet are its graves;

But peaceful sleep is ever there,

Beneath the dark blue waves.

T HE O CEAN

Nathaniel Hawthorne

PROLOGUE

The dark hull of the submarine rose a few inches above the waterline, belying the impressive metal body submerged below. Pale moonlight glinted off the quiet ocean as small waves lapped rhythmically against the hull. The submarine was 40 feet long, cylindrical down most of her slim length, but with a tapered, wedge-shaped bow and stern that hinted at how quickly she could slice through the water. Two narrow, oval conning towers rose above the peak of the rounded hull, and a double row of small, glass deadlights punctuated the surface between them. The deadlights, with their thick, imperfect, handmade glass, provided the only means for the moonlight to pierce the submarines bulk, and the only sign that there might be a crew within.

The HL Hunley was lying in wait to the east of Charleston Harbor, off the coast of South Carolina. The submarine had been there for months, practicing for her crucial mission and waiting patiently for flat seas.

Her bow carried the true source of her threat. A spar made of wood and metal was bolted securely to a pivot on the bottom corner of the boats leading edge, and at the far end of this spar was a copper cylinder the size of a keg: the boats torpedo. The torpedoes of the time were simple stationary bombs, very different from the modern, independent devices that can propel themselves through the water from a great distance. To complete her mission the Hunley would need to approach her target closely, then use this spar to press the charge directly against the side of her enemys hull. As the submarine bobbed slowly in the waves, the lethal orange cylinder bobbed with it.

The propeller on the long submarine began to spin into motion. Its three arced blades cut through the cold February water and accelerated the sub in the direction of the open ocean. The tide was beginning to turn, and the outgoing current would further speed the Hunley toward her target.

On the deck of the Union ship USS Housatonic, the sailors gazed out over the flat seas of the Atlantic. Confederate torpedoes, later renamed mines by a future generation of warriors, lay peppered throughout the waters of Charlestons harbor, drifting idly on weighted tethers anchoring them to the ocean floor. The Housatonic had reached an uneasy dtente with these hidden underwater bombs by staying in the shallows outside the harbors mouth, but the Confederates were always trying new ways to attack. There had been reports of small, stealthy boats armed with charges on spars, and even some reports of mysterious boats that could supposedly travel completely under the water. The Housatonic was just one of many Union ships that had been prowling the waters outside Charleston for months, and tonight, like every other night, the cool air was punctuated by the sounds of Union artillery gradually chipping away at that citys stately stone buildings. She tugged gently against her anchor as the tidal currents shifted and pulled her seaward. The Hunley swam closer.

It took hours to reach the ship.

The Hunley approached the hulking wooden mass of the Housatonic, and the comparatively tiny submarine began to pick up speed. A sailor on watch spotted the narrow sliver of the dark metal hull exposed above the surface of the water and alerted the other sailors on board, but submarines were new technology and the men did not yet understand the deadly shape in the water. For a few brief minutes speculation ran wild among the crew, and the sailors did nothing as they comforted themselves that the dark shape was merely a porpoise coming to play near the ship. They realized the approaching danger too late, and the crew scrambled for firepower, any firepower, that could be trained to hit the oncoming object. The submarine remained undeterred.

HL Hunley pressed her torpedo snugly against the Housatonics side. One of the three thin metal rods protruding from the leading face of the bomb depressed slightly against the wooden hull. The fragile wire holding the rod precariously in place snapped, freeing the coiled and waiting energy of the compressed spring that was firmly wrapped around its body. As the spring rapidly expanded to its natural shape, the metal rod leapt backward in response and smashed against the thin wall of the compartment that was nestled in the back of the trigger. Inside the compartment were two small caps filled with mercury fulminate. The simple, elegant chemical was inherently unstable, dying for the slight nudge that would propel it into a cascade of cathartic release.

Any fire is a release of energy. Chemicals and materials in one state leap to a more stable, lower-energy state, like a rock rolling down to a lower-energy state at the bottom of a hill. The energy released from the reaction takes the forms of heat, sound, and light. An explosion is a similar reaction but pushed into higher speed.

The rod impacted the thin compartment wall directly opposite one of the unstable mercury fulminate caps, and the boulder was shoved violently off a massive cliff.