Copyright 2014 Brian Hicks

All rights reserved under International and Pan American Copyright Conventions.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

This edition is published by Spry Publishing LLC

315 East Eisenhower Parkway, Suite 2

Ann Arbor, MI 48108 USA

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014947283

E-book ISBN: 978-1-938170-61-4

For Zaldu and Akeem

Despite their villainous tendencies, they saved history

Contents

Its often said that a shipwreck is never found until it wants to be found. Ive added another axiom: When you discover a lost shipwreck, its never where its supposed to be.

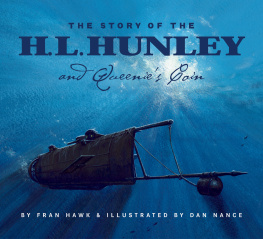

Brian Hickss unique perspective provides the true story of the Confederate submarine remembered as the Hunley from the beginning to the present. Through exacting research he reveals a fascinating phenomenon that provides an intellectual adventure. His every detail is visibly accountable as he preserves the time period with intimate research of the people and the undersea vessel that forever changed the history of naval warfare.

I once described swimming through a sunken ship as being the same as walking through a haunted house. There are always stories of people who perished while onboard. Many are the ghost ships that left behind an unsolvable mystery.

In prehistory, our ancestors early adventures on the waters of the world were not recorded. Somewhere in the fog of the distant past the first manned boat on water was probably a log with a Neanderthal straddling it. For years, anthropologists speculated early humans lived only on land and never ventured onto the oceans. Yet, how did they reach Australia, New Zealand, Japan or the shores of Africa?

Eventually they built simple wooden hulls that could carry more than two men, but not before they learned to shape a flat piece of wood into an oar. To use the wind they created rudimentary sails stitched from animal hides.

As the millenniums passed, boats became ships that were massive and vastly faster, with sails larger than a billowing cloud and far more resilient. Then came steam, diesel engines and eventually nuclear power. Today there are more than a thousand different types of ships, from aircraft carriers to tankers to container cargo vessels. And, the latest ship to appear not only on the surface of the sea but under it.

The submarine.

Underwater vessels have been around since 420 BC, when Aristotle described how Alexander the Great entered a cauldron and was lowered into the Mediterranean to see what was down there. Another nine hundred years passed until the first modern dive bell was built that enabled divers to remain under water from fifteen to twenty minutes for the exploration of a totally unknown world.

Through the centuries, diving bells were converted into undersea craft that could move from one point to another. Almost none were successful and many killed their inventors. Some were designed with war in mind. David Bushnells submarine was one of the first built to sink a warship. It came close in 1776 but failed. Other submersibles were created but none proved feasible.

The first underwater craft with the title of destroying a warship was the Confederate submarine Hunley. By sinking the sloop of war Housatonic in 1864, the Hunley finally showed it could be done, even if the sub killed three of its crews numbering a total of 21.

For the following 131 years the Hunley rested four feet beneath the seafloor silt, unseen, unfound and almost forgotten after sinking the Housatonic.

Some lost vessels are found within a few minutes after dropping the sensors from the side-scan sonar and the magnetometer over the side. That count is very low. A high number cannot be found and remain lost forever. In my case, finding a wreck runs around one discovery in six attempts. I was a babe in the woods on my first search for John Paul Joness ship the Bonhomme Richard. I didnt have the vaguest idea of what I was doing. My only discovery was a bar in Bridlington, England, that served Budweiser.

The crew was a rough bunch who smiled through broken and missing teeth. The engineer had the name Gonzo tattooed on his forehead. All that was missing were hooks for hands, black eye patches, peg legs and parrots on their shoulders.

Despite weeks of follies and drunken attempts to run straight grid lines, I was saddened six months later when I learned the ship and crew and Gonzo vanished the following December during a horrific storm in the North Sea.

The following year I decided to go after the H. L. Hunley. Off to Charleston I went with my son, Dirk, Craig Dirgo, Americas famous marine archaeologist Peter Throckmorton, and Doc Edgerton, the physicist genius who created the strobe light, the side-scan sonar and holds a hundred other patents.

The most important asset for any expedition is a crew who is dedicated. Every man who assembled in Charleston was committed to the search. Charts were poured over an untold number of times. The research was unending. Robert Fleming, a respected Washington marine investigator, dug through every record, large or small, that mentioned the Hunley.

On this expedition in 1980 we mowed the lawn a half-mile off Sullivans Island under the direction of Ralph Wilbanks, who was acting on behalf of South Carolinas Institute of Archeology. One morning Bill Shea, our magnetometer genius from Brandeis University, marine archaeologist Dan Koski-Karell, and my son Dirk steered their rubber Zodiac through Breach Inlet to begin eliminating possible targets within the beach to half-mile offshore.

That was 1980.

We returned in 1981 and dragged the magnetometer over a thousand miles. The only bad news was we didnt find the Hunley. Yet, this expedition was efficient. Every piece of equipment ran faultlessly throughout the entire month. We all stayed at a huge house on the beach with a terrific cook and a cooling offshore breeze from the sea.

But still no luck.

I didnt return until 1994. Meeting up again with my good friend Ralph Wilbanks, who was now operating his own survey company along with marine archaeologists Wes Hall and Harry Pecorelli, we began rechecking all the former targets from the other expeditions in case we missed something. Bob Fleming, the finest maritime research expert in Washington, found the board of inquiry record on the loss of the Housatonic, the warship sunk by the Hunley. The record still had a wax seal that had never been broken since 1864.

The most pertinent information he gleaned from the record of the inquiry was a report from a crewman on the Housatonic. He was a landsman named Robert Flemming, coincidently with the same name as Bob. When asked if he saw the torpedo boat after the sinking, Flemming said he spied a blue light 300 hundred yards off the starboard quarter directly in front of the Canandaigua, its sister blockading sloop of war.

That was a huge turning point. For years everyone including me thought the Hunley was headed back to shore when it sank. This was supported by soldiers on Sullivans Island who claimed they saw the blue light, which signaled the Hunley was starting toward shore. They then lit a bonfire to guide the subs return.

Next page