EUMENES Publishing 2019, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

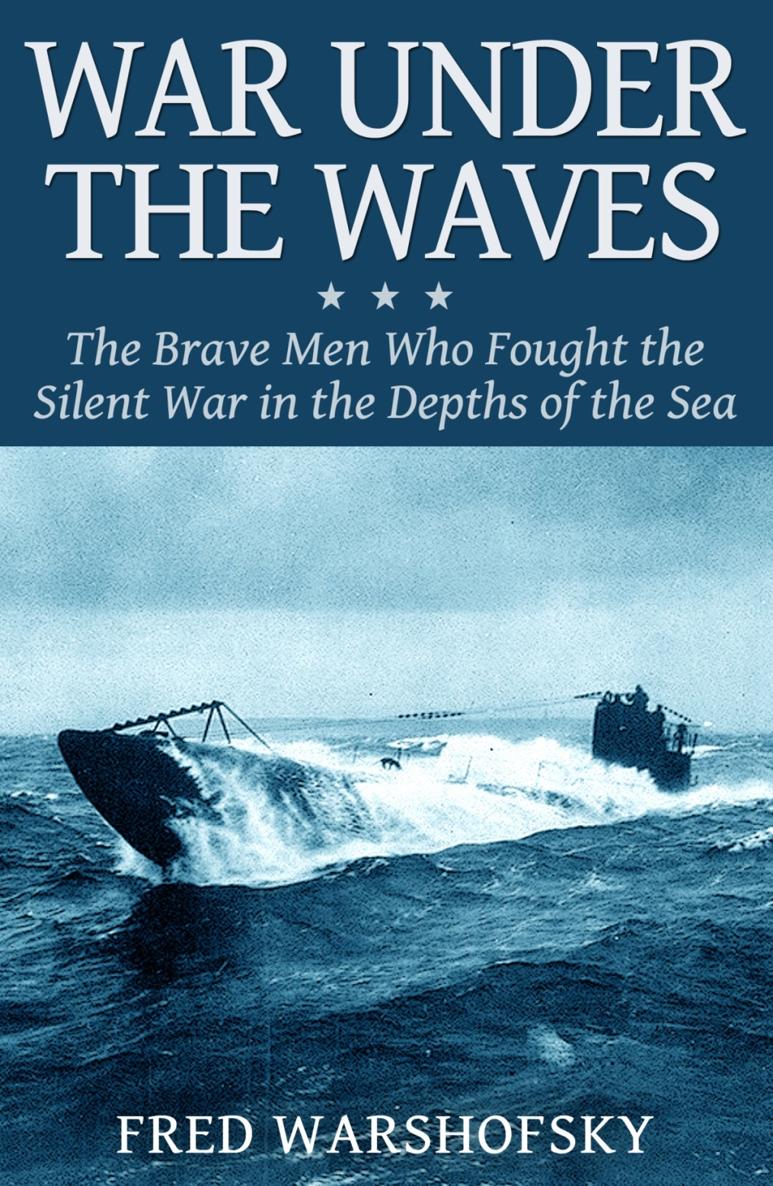

WAR UNDER THE WAVES

The Brave Men Who Fought the Silent War in the Depths of the Sea

FRED WARSHOFSKY

War Under the Waves was originally published in 1962 by Pyramid Publications, Inc., New York, New York.

Table of Contents

Contents

Table of Contents

REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to the Electric Boat Division, General Dynamics Corporation, for making available the great research resources of their Submarine Library in Groton, Connecticut This unique library, which is open to the public, is perhaps the most complete storehouse of submarine history that exists under one roof in the world.

Introduction

The submarinethat silent, deadly undersea raiderhas proved itself to be one of the most efficient tactical weapons ever invented. Both World Wars attest to this.

The history of the submarine, however, goes bade far beyond modern times. In the fourth century B.C., Alexander the Great, ruler of Macedonia and conqueror of what was then the known world, had ordered the construction of a glass barrel. When it was ready he entered and had himself lowered into the sea. The great conqueror swiftly realized the potential of his submarine, and according to Aristotle, used similar vessels to repel a fleet that was attempting to lift the siege of Tyre.

Alexanders brilliant use of the submarine, although recorded by the Greeks and inscribed in Persian folklore, failed to attract the attention of the Romans; and the submarine, as a weapon, was not used again in warfare. Civilizations rose and fell, the Dark Ages swept across Europe, and it was not until the Renaissance that the submarine again made an appearance.

Leonardo da Vinci, the Florentine artist, architect and scientist, conceived the plans for an underwater warship. So terrible were his visions of the destruction the submarine could cause, that he suppressed his plans. War, he reasoned, was horrible enough.

Again the submarine disappeared from human consciousness. About one hundred years after the death of Leonardo, a strange Dutchman named Cornelius van Drebbel arrived in England. He cut a comical figure at the court of King James the First with his weird talk of an Eel Boat that could prowl beneath the surface of the sea. But King James heeded the words of Mother Shipton, a prophetess, who cryptically predicted: Underwater men shall walk, shall ride, shall sleep, shall talk.

Van Drebbel was allowed to pursue his experiments on the Thames River. In 1620, his Eel Boatconstructed of wood, covered with oil-soaked strips of leather, and propelled by oarswas completed. King James was so delighted with the strange craft that he reportedly took a short voyage under the surface of the Thames.

But if the Eel Boat was little more than a royal oddity, the submarine had not long to wait before it was to become a fearful weapon of war. It was in 1775 that an American inventor named David Bushnell offered the struggling colonies a means of destroying the British Fleet

1. The Incredible Water Machine

Sergeant Ezra Lee, of General Samuel H. Parsons Colonial Army, goggled in amazement at the barrel-like contraption before him. You expect to sink the British fleet with this? he asked incredulously of the slight, shy-looking inventor who stood beside him.

The Turtle, replied David Bushnell, is a submersible. In it you can go under water right up to a British ship, plant a charge of gunpowder against the hull, and blow it to eternity!

Lee, a heavily muscled man with the springing movements of an athlete, circled Bushnells weird-looking invention. He nodded his head several times, leaned over and rapped the curving oak sides, and finally stepped once again in front of the inventor. She might work at that, he said. If you will teach me to operate the water machine, I will be a willing pupil.

It was late spring, 1776, and the War of Independence was not going well. The ragged Colonial Army was being driven back from New York; General Sir William Howe was overrunning Long Island, and his brother, Admiral Lord Richard Howe, sat with his fleet astride New York harbor. This mighty British fleet had already closed most of the colonial ports and had driven the American ships from the sea. Nothing, it seemed, could challenge the British.

Then General Samuel Parsons heard of an eccentric thirty-five-year-old Connecticut inventor, just graduated from Yale, who had been experimenting with underwater explosions and had developed some form of water machine that would travel beneath the surface. Parsons had enough of a nautical background to realize that such a machine, if it really worked, could play havoc with the British fleet.

The Generals initial sight of the worlds first combat submarine could hardly have been called inspiring. The Turtle was the most ungainly looking vessel ever to touch water. Only seven feet high, four feet long and three feet thick it resembled nothing so much as an egg or a clam standing on end. The hull was of oaken planks, curved like barrel staves and calked and tarred at the joints. The interior was just large enough to hold one man and enough air to keep him alive for thirty minutes.

At her stern was a small rudder controlled from the inside by a lever which ran through a crude and leaky stuffing box. On the bow was a flat, single-blade propeller which would pull the submarine ahead at a speed of two knots when the operator vigorously turned a crank handle inside. But the Turtle , as it was called for its lack of speed, was far ahead of its time, and its ballast system was a work of sheer genius. The principles which Bushnell developed almost two centuries ago are similar to those used even in todays nuclear submarines. He described the system for Thomas Jefferson:

The vessel was chiefly ballasted with lead, fixed to its bottom....The Vessel with all its appendages, and the operator, was of sufficient weight to settle very low in the water. About two hundred pounds of lead at the bottom for ballast, could be let down forty or fifty feet below the Vessel. This enabled the operator to rise instantly to the surface of the water in case of accident.

When the operator would descend he placed his foot upon the top of a brass valve, depressing it, by which he opened a large aperture in the bottom of the Vessel, through which the water entered at his pleasure. When he had admitted a sufficient quantity, he descended very gradually; if he admitted too much, he ejected as much as was necessary to obtain an equilibrium, by the two brass forcing pumps, which were placed at each hand. Whenever the Vessel leaked or he would ascend to the surface, he also made use of the forcing pumps. When the skillful operator had obtained an equilibrium, he could row upward or downward, or continue at any particular depth with an oar, placed near the top of the vessel, formed upon the principle of the Screw, the axis of the oar entering the Vessel; by turning the oar one way he raised the Vessel, by toning it the other way he depressed it.