By Daisy Goodwin

Silver River

Edited by Daisy Goodwin

101 Poems That Could Save Your Life

For my father Richard Goodwin my ideal reader

Thats my last Duchess painted on the wall

My Last Duchess, Robert Browning

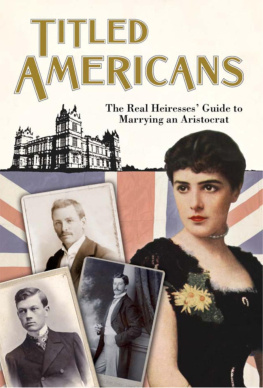

The American girl has the advantage of her English sister in that she possesses all that the other lacks

Titled Americans , 1890

Contents

Part One

LADY FERMOR-HESKETH.

MISS FLORENCE EMILY SHARON, daughter of the late Senator William Sharon, of Nevada.Born 186.Married, in 1880, to SIR THOMAS GEORGE FERMOR FERMOR-HESKETH, seventh Baronet; born May 9, 1849; is Major of Fourth Battalion, Kings Regiment; has been Sheriff of Northamptonshire; and is a Deputy Lieutenant and Justice of the Peace of the County.Issue:Thomas, born November 17, 1881.Frederick, born 1883.Seats: Rufford Hall, Omskirk, and Easton Neston, Towcester.Creation of title, 1761.

The family has been settled in Lancashire for seven hundred years.

Titled Americans , A List of American Ladies Who Have

Married Foreigners of Rank , 1890

Chapter 1

The Hummingbird Man

Newport, Rhode Island, August 1893

T HE VISITING HOUR WAS ALMOST OVER, SO the hummingbird man encountered only the occasional carriage as he pushed his cart along the narrow strip of road between the mansions of Newport and the Atlantic Ocean. The ladies of Newport had left their cards early that afternoon, some to prepare for the last and most important ball of the season, others so they could at least appear to do so. The usual clatter and bustle of Bellevue Avenue had faded away as the Four Hundred rested in anticipation of the evening ahead, leaving behind only the steady beat of the waves breaking on the rocks below. The light was beginning to go, but the heat of the day still shimmered from the white limestone faades of the great houses that clustered along the cliffs like a collection of wedding cakes, each one vying with its neighbour to be the most gorgeous confection. But the hummingbird man, who wore a dusty tailcoat and a battered grey bowler in some shabby approximation of evening dress, did not stop to admire the verandah at the Breakers, or the turrets of Beaulieu, or the Rhinelander fountains that could be glimpsed through the yew hedges and gilded gates. He continued along the road, whistling and clicking to his charges in their black shrouded cages, so that they should hear a familiar noise on their last journey. His destination was the French chateau just before the point, the largest and most elaborate creation on a street of superlatives, Sans Souci, the summer cottage of the Cash family. The Union flag was flying from one tower, the Cash family emblem from the other.

He stopped at the gatehouse and the porter pointed him to the stable entrance half a mile away. As he walked to the other side of the grounds, orange lights were beginning to puncture the twilight; footmen were walking through the house and the grounds lighting Chinese lanterns in amber silk shades. Just as he turned past the terrace, he was dazzled by a low shaft of light from the dying sun refracted by the long windows of the ballroom.

In the Hall of Mirrors, which visitors who had been to Versailles pronounced even more spectacular than the original, Mrs Cash, who had sent out eight hundred invitations for the ball that night, was looking at herself reflected into infinity. She tapped her foot, waiting impatiently for the sun to disappear so that she could see the full effect of her costume. Mr Rhinehart stood by, sweat dripping from his brow, perhaps more sweat than the heat warranted.

So I just press this rubber valve and the whole thing will illuminate?

Yes indeed, Mrs Cash, you just grasp the bulb firmly and all the lights will sparkle with a truly celestial effect. If I could just remind you that the moment must be short-lived. The batteries are cumbersome and I have only put as many on the gown as is compatible with fluid movement.

How long have I got, Mr Rhinehart?

Very hard to say, but probably no more than five minutes. Any longer and I cannot guarantee your safety.

But Mrs Cash was not listening. Limits were of no interest to her. The pink evening glow was fading into darkness. It was time. She gripped the rubber bulb with her left hand and heard a slight crackle as light tripped through the one hundred and twenty light bulbs on her dress and the fifty in her diadem. It was as if a firework had been set off in the mirrored ballroom.

As she turned round slowly she was reminded of the yachts in Newport harbour illuminated for the recent visit of the German Emperor. The back view was quite as splendid as the front; the train that fell from her shoulders looked like a swathe of the night sky. She gave a glittering nod of satisfaction and released the bulb. The room went dark until a footman came forward to light the chandeliers.

It is exactly the effect I had hoped for. You may send in your account.

The electrician wiped his brow with a handkerchief that was less than clean, jerked his head in an approximation of a bow and turned to leave.

Mr Rhinehart! The man froze on the glossy parquet. I trust you have been as discreet as I instructed. It was not a question.

Oh yes, Mrs Cash. I did it all myself, thats why I couldnt deliver it till today. Worked on it every evening in the workshop when all the apprentices had gone home.

Good. A dismissal. Mrs Cash turned and walked to the other end of the Hall of Mirrors where two footmen waited to open the door. Mr Rhinehart walked down the marble staircase, his hand leaving a damp smear on the cold balustrade.

In the Blue Room, Cora Cash was trying to concentrate on her book. Cora found most novels hard to sympathise with all those plain governesses but this one had much to recommend it. The heroine was handsome, clever and rich, rather like Cora herself. Cora knew she was handsome wasnt she always referred to in the papers as the divine Miss Cash? She was clever she could speak three languages and could handle calculus. And as to rich, well, she was undoubtedly that. Emma Woodhouse was not rich in the way that she, Cora Cash, was rich. Emma Woodhouse did not lie on a lit la polonaise once owned by Madame du Barry in a room which was, but for the lingering smell of paint, an exact replica of Marie Antoinettes bedchamber at le petit Trianon. Emma Woodhouse went to dances at the Assembly Rooms, not fancy dress spectaculars in specially built ballrooms. But Emma Woodhouse was motherless which meant, thought Cora, that she was handsome, clever, rich and free. That could not be said of Cora, who at that moment was holding the book straight out in front of her because there was a steel rod strapped to her spine. Coras arms ached and she longed to lie down on Madame du Barrys bed but her mother believed that spending two hours a day strapped to the spine improver would give Cora the posture and carriage of a princess, albeit an American one, and for now at least Cora had no choice but to read her book in extreme discomfort.

At this moment her mother, Cora knew, would be checking the placement for the dinner she was holding before the ball, tweaking it so that her forty odd guests knew exactly how brightly they sparkled in Mrs Cashs social firmament. To be invited to Mrs Cashs fancy dress ball was an honour, to be invited to the dinner beforehand a privilege, but to be seated within touching distance of Mrs Cash herself was a true mark of distinction, and was not to be bestowed lightly. Mrs Cash liked to sit opposite her husband at dinner ever since she had discovered that the Prince and Princess of Wales always faced each other across the width not the length of the table. Cora knew that she would be placed at one end sandwiched between two suitable bachelors with whom she would be expected to flirt just enough to confirm her reputation as the belle of the season but not so much that she compromised her mothers stratagems for her future. Mrs Cash was throwing this ball to display Cora like a costly gem to be admired but not touched. This diamond was destined for a coronet, at least.

Next page