INTRODUCTION

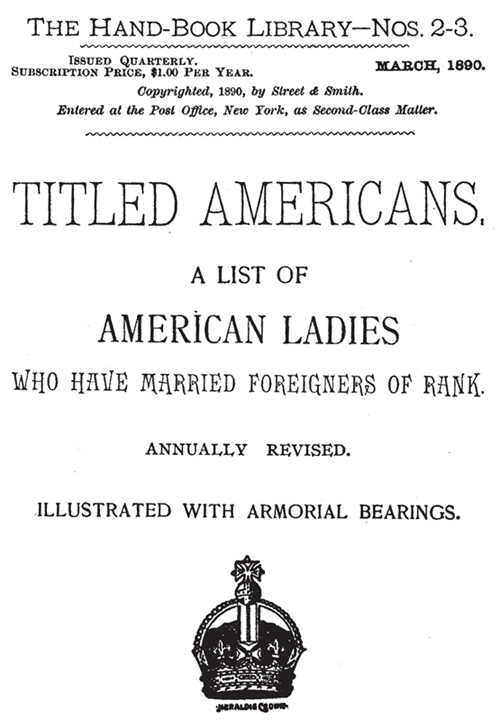

Bessie. Jennie, Lizzie. Mary, Nellie and Annie. There was something fairly ordinary in the names of these young American heiresses who had embarked upon the great adventure of a marriage into the European aristocracy. They suggested perhaps a graduating class of a high school in Connecticut or Ohio. But these are far from ordinary Americans, for their names appear in Titled Americans, an 1890 book that revealed the wealthiest and most socially ambitious families of late nineteenth-century America, and the titled European bachelors whose hearts their daughters might hope to conquer.

It has been estimated that 454 American heiresses married European aristocrats in the late nineteenth century, and thus acquired, at considerable expense, hereditary titles of nobility. 136 bagged Earls or Counts, forty-two married princes, seventeen married dukes, nineteen married viscounts, thirty-three married marquises, and there are forty-six wives of baronets and knights, and sixty-four baronesses. Scholars such as Maureen Montgomery and Marian Fowler have significantly enriched our understanding of the headhunting heiresses.

People were indeed curious about such fairy-tale marriages. In the last two or three decades of the nineteenth century, there had been an explosion of press interest in the doings of the wealthy, who led by the regal Astors, Vanderbilts, Morgans and Goulds became objects of intense press scrutiny. The rich constituted the first true celebrities in American life, soon to be followed by opera divas, Broadway performers, singers, movie stars, professional athletes, gamblers and gangsters. Celebrity was an elastic category in America, and the aspiration to be a celebrity swept across the nation in the late nineteenth century. Parties given at the highest levels of society were described in the press. The summer cottages at Newport (which were really quite handsome French Renaissance country estates) were photographed, and praised in lavish, sycophantic detail. Tourists headed for Fifth Avenue and Newport, hoping for a sight of the celebrity hostesses and heiresses of the day. There was newly created space for society news in many major American newspapers. In an era of increasing journalistic specialization, there were newly hired columnists and reporters devoted to high society.

Publishers were quick to notice this development in the journalistic marketplace. An explosion of guides to the way of life of the bon ton, lists of the fashionables and ultra-fashionables, and guides which sought to rank the richest men, the most exclusive gentlemens clubs, and the most eligible bachelors and society belles soon followed.

Among the earliest ventures was The List, a directory of social information published by Maurice M. Minton in 1880, aimed at the several thousand families who made up society in New York City. It was followed by Charles H. Crandalls The Season: An Annual Record of Society in New York, Brooklyn, and Vicinity (1883). The viperish society gossip weekly magazine, Town Topics, began its notorious career in 1885. The most influential and long-lived guide to those at the highest social standing was The Social Register (appearing annually from 1887). But it was a remark by the social arbiter Ward McAlister which set the seal upon the idea of aristocratic New York city. Why, he remarked to a journalist, there are only about four hundred people in fashionable New York society. Across the nation there was an outcry. Who were the 400? Who was excluded?

The 1890s was a decade in which social conflict reached unprecedented heights, and hardship was a reality for many Americans. Consciences were agitated by the documentation of the lives of the New York slum-dwellers in Jacob Riis How The Other Half Lives, published in 1890. But newspapers in what was called the Gilded Age seemed to be more concerned to chronicle the lives of the rich and socially eminent. The idea of McAllisters 400 in the 1890s seemed a more interesting social phenomenon. Titled Americans emerged out of that swirling curiosity about the social elite.

Novelists of the distinction of Henry James and Edith Wharton found in the social aspirations of American womanhood, and the reality of their encounter with European aristocrats, a subject of potential tragedy. But the nuanced portraiture of The Portrait of a Lady or The House of Mirth scarcely shaped the avid interest of the majority of novel-readers or the target audience for daily papers. The interest was unquenched, and largely uncritical.

The most astringent view of these golden marriages came from those who assumed that there were financial transactions and substantial dowries behind them. The New York Times suggested in 1893 that as much as $50 million might have accompanied the American brides as they sailed across the Atlantic for their new lives in the decayed and impoverished estates of the great aristocratic families. In 1911 Gustavus Myers estimated the true cost of the transatlantic marriages at something like $220 million.

The problem with putting a figure, a very large figure, to the transatlantic marriages is that it over-simplifies what was a complex process. Marriage into European noble families was not something to be settled by hauling out a cheque book and buying a husband for Bessie. Jennie, Lizzie. Mary, Nellie or Annie.

Consider the case of Lily Hamersley and Jennie Jerome, New York heiresses who became sisters-in-law by marrying into the Marlborough family. Jerome, who married Lord Randolph Churchill, third son of the 7th Duke, in 1874, appears in Titled Americans. Hamersley, who married Lord Randolphs older brother, George Spencer-Churchill, 8th Duke of Marlborough, in 1888, is mentioned in the Preface. Their situations were intriguingly similar. Lord Randolph Churchills biographer, R.F. Foster, found evidence that Francis Knollys, a family friend and equerry to the Prince of Wales, compiled detailed reports on the state of the Jerome finances. It was reported in the New York press that the 8th Duke ordered that a strict and searching investigation into Mrs. Hamersleys pecuniary eligibility should be undertaken. The Jerome family had doubts about Lord Randolph. He was regarded by Jeromes mother as a disaster waiting to happen: he was hasty rash headstrong unconsidered impulsive. Lily Hamersley, a worldly and quick-witted widow of a wealthy New York real estate mogul, looked no less closely into the 8th Dukes finances and reputation. That he was divorced, and that his ex-wife was still living, raised no end of problems within the Anglican and Episcopalian communities. There was also an illegitimate son, and his having been named as a co-respondent in the 1886 divorce trial of Lady Colin Campbell.

And when everything was settled, it was time to bring in the lawyers for a careful consideration of the settlement, especially taking into account the different legal frameworks which applied to the property of married women in the United States (where a bride retained her property and wealth) and Great Britain (where husbands assumed unrestricted control over the wealth and property of the women they married). Running through the first series of Julian Fellowes Downton Abbey, first aired on British television in 2010, was the dire consequences for the heiress played by Elizabeth McGovern when she married the Earl of Grantham. On their marriage her great fortune was incorporated into the comital entail, in perpetuity. A wise heiress, and her parents and lawyers, would need to know about the perils of such a marriage. There was indeed much to negotiate. And when the families objections seemed interminable, it was sometimes necessary to force their hands. Winston Churchill was born seven months after the wedding of Jennie Jerome and Lord Randolph Churchill. The 7th Duke and the Duchess were not reconciled, and declined to attend the wedding.