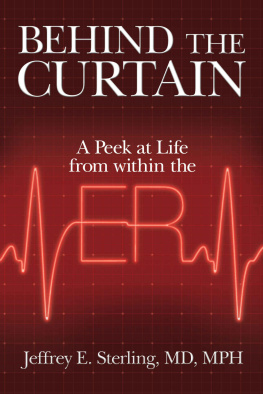

ER : Behind the Curtain

The Survivalis t s Guide to the ER

Dr. Gary D. Marks

Dedicated to past, present and future ER interns

--and all their patients.

Thank you.

Sections

Part 1:

The Journey Begins

Part 2:

Life On The Outside: Experiences Moonlighting As An Attending Physician

Glossary of Terms:

Definitions of commonly used medical terms

Disclaimer

This book represents the personal account of my training and experiences as an ER doctor. Medical technology and knowledge are constantly changing, therefore the medical information provided here is for general information and to provide context to the stories, and should NOT be treated as advice.

There is no guarantee or assurance whatsoever that any statement contained or cited in this text is correct, precise, complete, without error or up-to-date.

The information in this text is provided without any warranties, expressed or implied.

Any medical decision must be discussed with your physician. The information in this text is NOT a substitute for advice from your doctor and must NOT be treated as such. If you think that you are suffering from any of the conditions in this text or wish to make any changes to your overall healthcare plan, you should immediately discuss this with your doctor or seek immediate medical attention from a health care professional.

You should never use this text as a tool to guide medical decisions or to refute medical advice from your medical professional or doctor.

Part 1

The Journey Begins

W e re all in the same family. Everyone in the world. There was the first person and they had all these people. So everyon e s the same family---

Sofia O.

One fine day....

Does n t that hurt with him awake like that ? I asked.

No, all you need to do is numb the skin and they do just fine , the neurosurgical resident replied.

As I watched the patient squirm, I was n t sure I believed the surgeo n s proclamation. The stroke victim was fully awake while the drill directed by the resident penetrated his skull. Due to the affect of the stroke on his speech center, the patient could n t disagree with the neurosurgeo n s assertion as to the comfort of the procedure even if he wanted to. Besides, I thought to myself, if someone were going to bore into my head, I would n t want to be awake and listening to the drill. So, I ordered a sedative to be given to the patient despite the neurosurgeo n s reassurances. After that, the patient seemed more comfortable, and so was I.

Suddenly, the drunken man, who was lying right next to the stroke-drill-in-his-brain-guy, exploded with vomit. Chunks flew everywhere. It got all over me, and some flew up toward the neurosurgeon as he was drilling into the patien t s head. I think some got on the neurosurgeo n s leg, but none made it into the patien t s brain, which is always a good thing to avoid.

Whoa! Hey this is supposed to be a sterile procedure. Keep that guy from throwing up all over me, will you ? The neurosurgeon yelled.

Well , I responded , you're in the Emergency Department, a completely uncontrolled environment. You could always take the patient to the operating room and yo u d have a much more sterile setup .

Well, ther e s no time for that .

We moved the patients as far apart as possible in our little critical area, just incase more vomit-fountain was on its way.

We need help on the ramp ! yelled one of the nurses from the front of the ER.

I dropped everything and ran out onto the ramp to see what was going on. The ramp was the drive-up area for the ER where ambulances brought patients, but it was also where gang members and others tended to dump injured or overdosed people who needed emergent care. We never knew what w e d find out there when we heard those words , Help needed on the ramp !

As I ran through the double sliding glass doors and out into the night air, I saw that a car had been driven up the ramp. It was a large old boat of an American car, and it was riddled with bullet holes. Inside, two people were trying to get out of the back seat while another lay still in the drive r s seat screaming, and a fourth lay limp and unmoving across the lap of the driver on the front passenger side. Altogether, there were four young African-American males in the car, and each one had been shot.

The driver had a gunshot wound to his chest and was having difficulty breathing. Despite his own chest injury, he was yelling, and signaling toward the front seat passenger , Help him! Help him !

A junior resident was with me, as was one of the attendings. The front seat passenger was motionless and had a gunshot wound to his head. There was brain matter matted in his hair along the back of his scalp from the exit wound. It looked as if the bullet entered near his temple and blew out his occiput. The entry wound was a mere do t almost unnoticeable. The exit wound in the back of his head, however, was about the size of a silver dollar. Around the hole the surrounding bone was shattered and splintered.

The two patients in the back seat were quickly out of the car. One had been shot in the leg and was limping around, screaming loudly. The other was holding his stomach. Although he was out of the vehicle, he was not asking for help and remained very quiet. He had a scared and disconnected expression on his face.

Holes were punched through the car making it look like a piece of Swiss cheese. The floor of the passenge r s front seat was covered in blood, and other body fluids. It made me realize how silly all those movies were which showed a person getting shot at while protected behind his vehicle door. This was an old 197 s steel tank of a car, and the bullets passed through as if it were made of paper.

We threw the patient with the gunshot wound to his head onto a gurney and began to wheel him into the ER. He was completely limp and lifeles s like a rag doll.

The attending grabbed the junior resident and gesturing toward the head wound patient he said in his enigmatically calm voice , This on e s yours .

Three years earlier...

Introduction:

My Residency in Emergency Medicine

I was always told that medical school would fly by and be over in a flash. Looking back, it now seems to have passed in a single moment, self-contained in a quantum unit of time, or tick of the clock.

My first two years of medical school were spent in a classroom, trying to learn the intricacies of the living human by looking at two-dimensional drawings and photocopied words on hundreds of handouts. The second two years were my only clinical experience in medical school. As a third and fourth year medical student, I rotated through the different hospital specialties: everything from surgery, to internal medicine, to pediatrics. It was my job to help the interns and residents with their patient load and make their lives a little easier. In return, they were supposed to spend their precious spare time teaching me medicine. Although this system usually worked, often it did n t.

As a student I never had any true patient responsibility. I always knew that the intern over me would make any final decisions, and that in effect, much of what I did was simply busy work. Although my medical education was probably about the same as most medical students across the country, I felt completely ill-prepared for the task that lay before me: My internship and residency in emergency medicine!

Since my first year of medical school I knew that I wanted to become an emergency medicine physician. To explain why was not as easy. I ran into the same problem when I began writing the application essays to the different emergency medicine residency programs around the country. They all asked the same question--"Why do you want to be an Emergency Medicine Doctor?" It would have been easy to fall back on the same platitudes and niceties that got me through most of my college English literature classes. However, I wanted to kno w wh y myself.

Next page