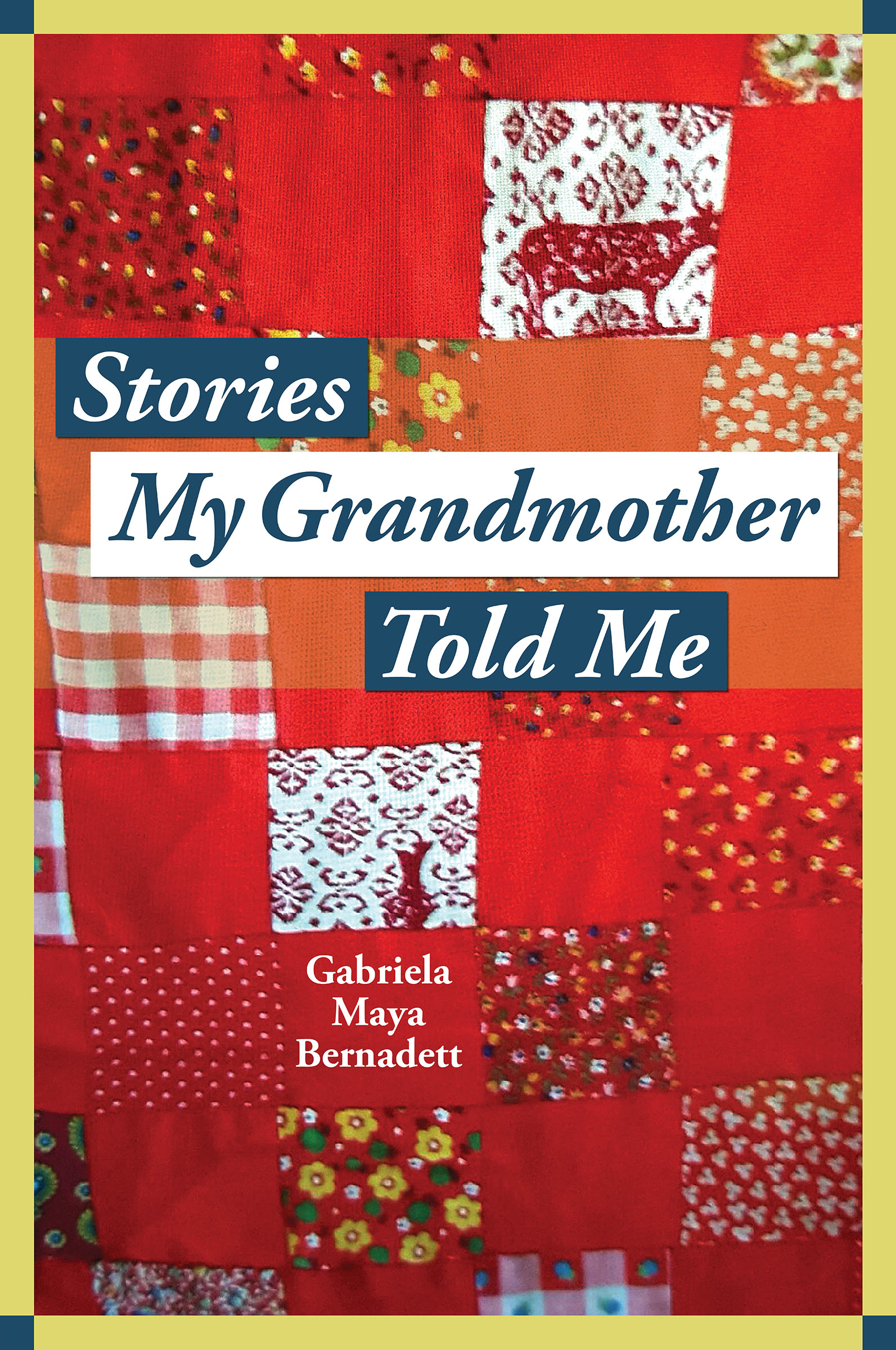

Disclaimer #1: The story you are about to read is about real people, real places, and real events that happened. The story attempts to capture, as best as possible, a womans memory of her life, and that womans granddaughters memories of how she heard these stories growing up. Any inconsistencies can be attributed to the imperfect way our memories understand our life experiences, and to the simple passage of time, which can often obscure exact details and exact dialogue.

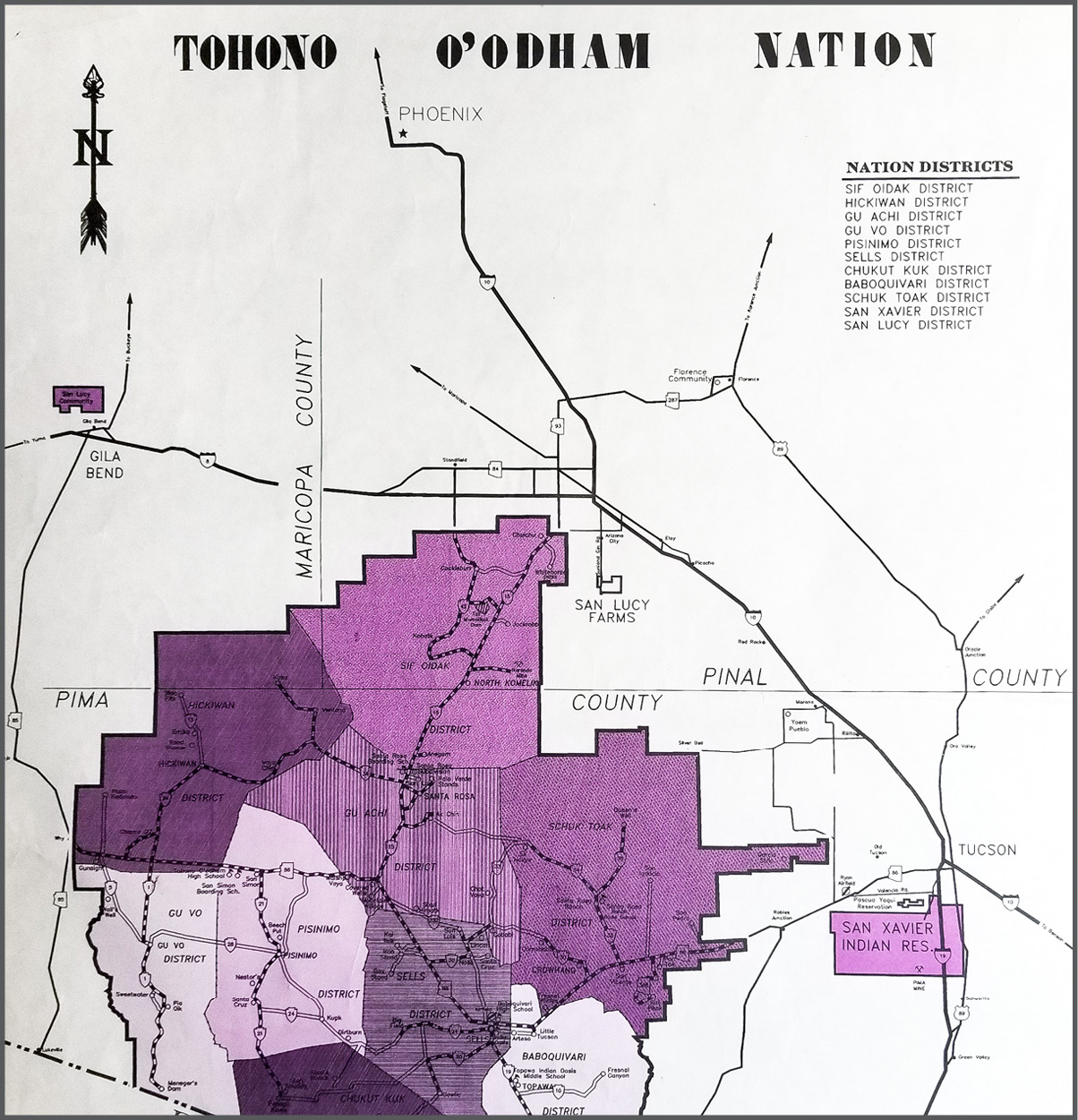

Disclaimer #2: Different understandings of Tohono Oodham language, pronunciations, or ceremonial descriptions are to be expected, as the Tohono Oodham Nation is vast and there are different accents, different experiences, and even different ways of doing ceremonies, depending on the region of the reservation a person is from.

Prologue

T here is perhaps no scene more timeless than an elder telling a group of precocious youngsters about life back in the day.

Sometime in the late 20th century, in a sprawling, one-story house nestled in a hilly Southern California suburb, two youngsters gather on a white couch in the living room. The room is arranged so that the couch is facing a gigantic window, with an armchair next to the couch and a table in front. The couch itself, upon closer inspection, has flowers embroidered on it in colorless thread. There is a plant in the corner of the room, and family pictures line the walls. The two youngsters have just eaten dinner, and the sun is setting outside. It is a summer evening, and the colors of the sunset cast a beautiful shadow, almost as if the golds, reds, and pinks of the sun are in the room itself.

An elder comes in, takes a seat in the armchair next to the couch, and begins not with a story, but with silence. Shes in her 70s, though the absence of wrinkles and a cane suggests someone much younger. She is about 5 feet 9, with a broad nose, deep-set eyes behind fashionable glasses, and short, curly hair graying at the edges. One of the youngsters, Maya, waits in rapt attention for her grandmother to tell her the same story she has heard since she could first understand words. She sits there, on one side of the couch, a mass of dark brown curls cinched to the nape of her neck with a black hair tie. Another girl, Tina, about five years younger, sits next to her. Her straight black hair is pulled high on her head into a sleek ponytail. At first glance, the two girls could not look more different; Maya with her curly brown hair and cinnamon-tinted skin, Tina with her straight black hair and skin three to four shades lighter. On closer inspection, however, the similarities become more evident: the small, slender noses, thin lips, and crescent-shaped eyes. Sisters, for sure. Tina breaks the silence.

Do you need anything, Grammy? she asks, getting up off the couch to go to the kitchen.

Just some water, the elder replies and again waits in silence until Tina comes back. Tina returns, setting the glass of water on the table in front of her grandmother. Esther brings the cup to her lips and takes a sip.

So how did you end up on the reservation again? Tina inquires, as if she hasnt heard the story a hundred times before. Esther sets the cup down and takes a deep breath.

There was a flyer, she says, and Maya and Tina snuggle together on the couch to get ready for a long night. They love it when the story starts here, from the beginning.

Chapter 1

Harlem

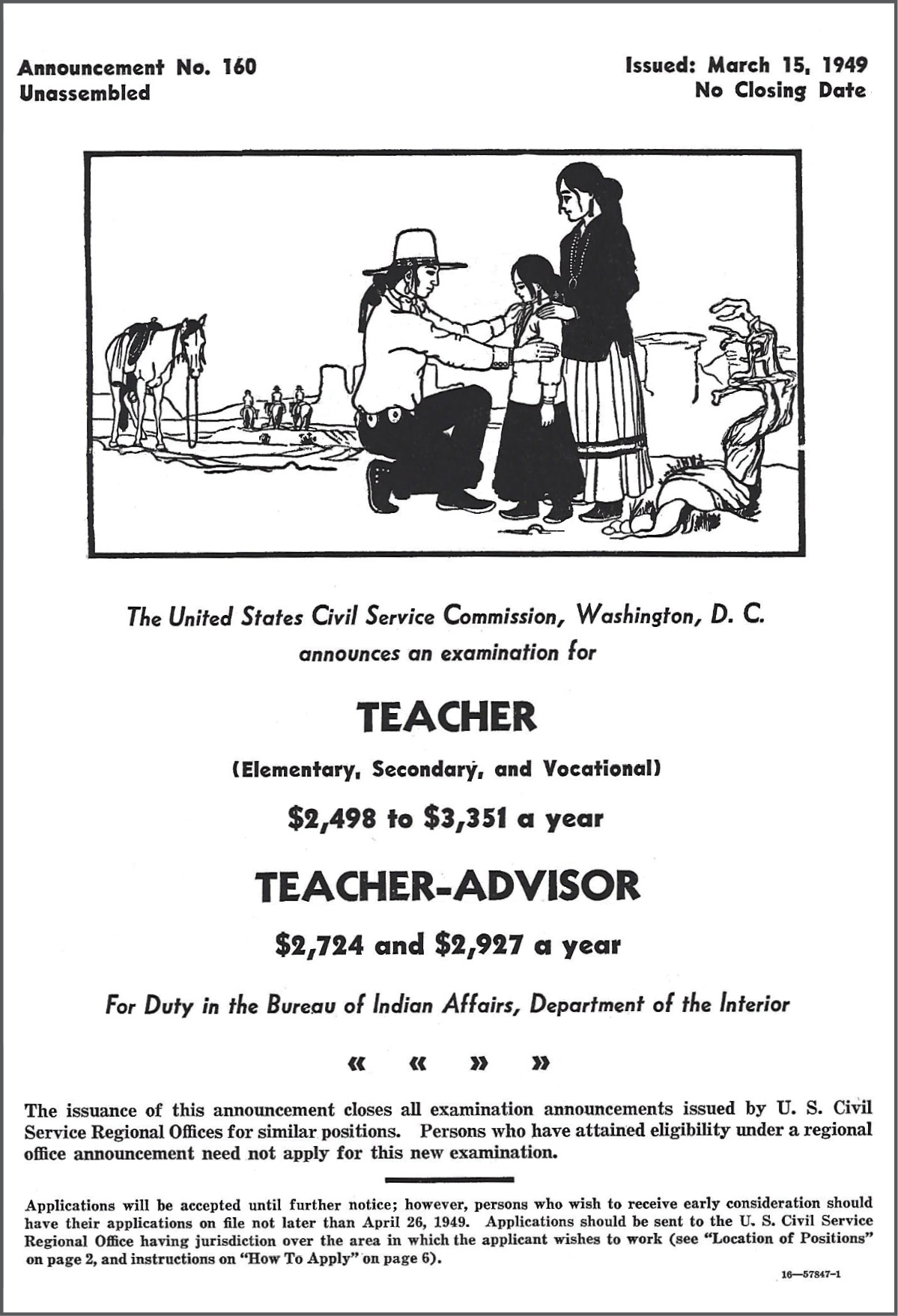

It was the picture that got her attention. As she left the library at 115th and Seventh Avenue, she saw it hanging right there on the bulletin board near the door. It was of an Indian family, huddled together next to a horse underneath the vast Southwestern Mountains, the desert sand beneath their feet. (Back then, in the 1940s, they were called Indians. It wasnt until about the 1960s that the term Native American came into popular use.) It was a scene Esther was not used to seeing. Being a Harlem girl, she would be more familiar with a Black family huddled next to the subway entrance beneath the New York City skyline. A vibrant, multi-ethnic community of Jews, Irish, Italians, Blacks, Puerto Ricans, and West Indians was all Esther knew. Mountains, Indians, desert, the Southwest these were all new to her, something that even the diverse borough of Harlem did not have. She was intrigued. She looked more closely at the picture and realized it was a poster for a program to teach Indians on reservations. She took down the address, some place in Washington, D.C. She would write to them, she thought, and see what this program could offer her.

It was not that Esther had any desperate need to leave Harlem. She loved it there, and couldnt imagine a better place to live. She was born on June 4, 1925, in an apartment at 98th and Lexington, through a home birthing program sponsored by the Harlem hospital. She grew up in a three-story brownstone a few blocks uptown with Daddy, Mother, Momma Sarah (Esthers maternal grandmother), and her two older brothers, Harold and Alfonso. Her aunts, uncles, and cousins all lived close by. Aunt Mattie would come by to chat, sometimes with a sweet potato pie in hand; cousin Lillian would periodically stop in to play with Esther; and Esther often saw Aunt Mary sitting on the stoop in front of the brownstone. This was similar to the family structure of the South, where there would be little houses close together, and the whole family took care of the kids; no one ever felt isolated or alone.

Mother and Momma Sarah had lived in Jacksonville, Florida, before they migrated up North. Esther and her brothers never asked them about it, but they would hear stories sometimes, bits and pieces of family history, lives lived in a time and place that Esther and her brothers could only imagine.

Back in Jacksonville, Mother would say, I walked around without shoes. We would save our shoes for Sunday school.

Harold and Alfonso would make a face. No shoes! they whispered to Esther, snickering. Esther knew what they meant. Walking around the swamps of Florida with nothing but your bare feet touching the wet ground and who knows what else? Ugh!

One day, as I was walking back from school, Mother continued, I was passing by the creek and saw a baby alligator. She pronounced the word creek like crick, a remnant of her Southern upbringing. I said to myself, Im gonna get me a baby alligator. So I jumped into the creek, grabbed it, held it with both hands, while the tail was whipping back and forth. It even hit me a couple times, I was surprised how strong its tail was. Esther could just imagine Mother, a tall, lanky, 12-year-old, wrestling an alligator barefoot in the muddy creek. I brought it home and put it in our tub that Momma used to wash clothes in. Momma came back home and saw the alligator in the tub, and she said, You need to put the alligator back in the water. But I just caught it! I told Momma. She said I still had to put it back. So I grabbed the alligator out of the tub and put it back in the creek. Momma Sarah would smile every time she heard Mother recall this incident. Very few stories about the South made her smile.

Sometimes, Mother would talk to Momma Sarah about Agnes, Esthers great-grandmother, who was born into slavery and freed when she was five years old.

As a young girl, she remembered other slaves on the plantation telling her, Youre so pretty, just like your mother Sally, Mother would say. They told her, You smile just like your mother.

Disclaimer #1: The story you are about to read is about real people, real places, and real events that happened. The story attempts to capture, as best as possible, a womans memory of her life, and that womans granddaughters memories of how she heard these stories growing up. Any inconsistencies can be attributed to the imperfect way our memories understand our life experiences, and to the simple passage of time, which can often obscure exact details and exact dialogue.

Disclaimer #1: The story you are about to read is about real people, real places, and real events that happened. The story attempts to capture, as best as possible, a womans memory of her life, and that womans granddaughters memories of how she heard these stories growing up. Any inconsistencies can be attributed to the imperfect way our memories understand our life experiences, and to the simple passage of time, which can often obscure exact details and exact dialogue.