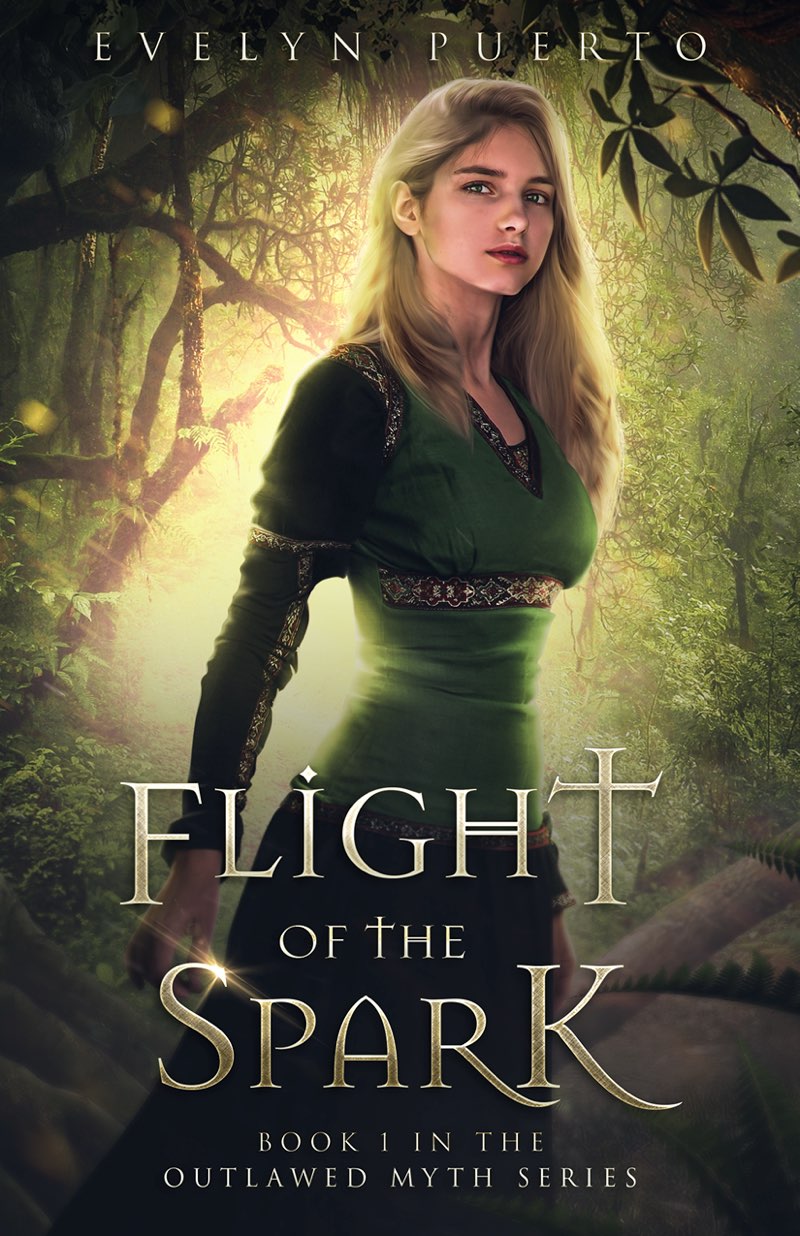

1

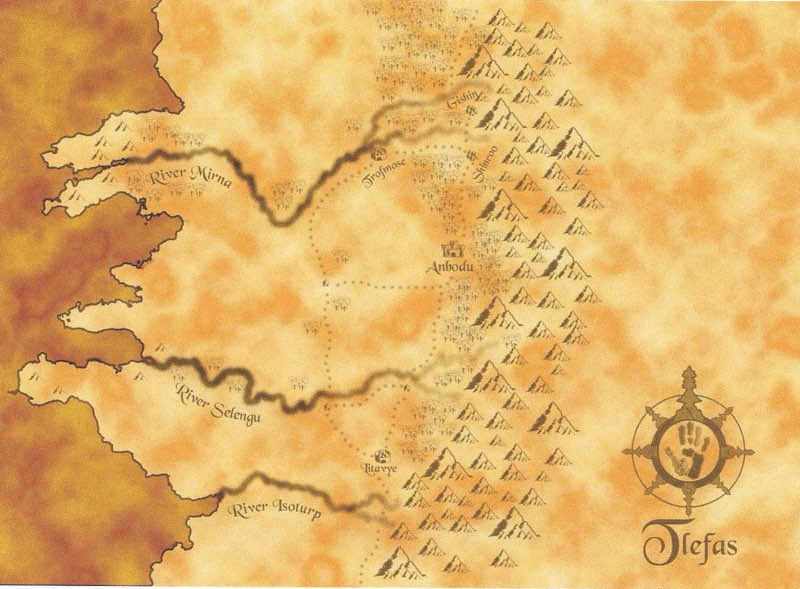

I skra wasnt sure about many things, except one: This would be a day shed remember her whole life. She stared at her mug of tea, lost in anticipation. Today, for the first time in her fifteen years, she was going to leave the village of Gishin.

People didnt often travel from village to village; it was considered an unnecessary risk, which made no sense to Iskra. The idea of seeing a new place and new people seized her imagination and sent tingles down her spine. She was confident that the thrill of something new would be worth the discomfort of a few hours on a wagon.

At first, her mother had been adamant: Iskra was not going anywhere. Undaunted, Iskra put her mind to convincing her mother. Every time her mother complained about the quality of candles, Iskra reminded her that better ones were to be had in Shinroo, along with soft woolen stockings and shawls. And shed heard a rumor that the shoemaker in Shinroo was already selling summer shoes, and Luza needed a new pair.

By some miracle, and perhaps by Iskras zealous attention to her chores and tireless arguing, her mother relented. In fact, she had no idea why her mother had granted her permission... maybe shed decided to indulge her daughter just as shed indulged in a little too much wine that night at the inn.

Whatever the reason, Iskra didnt care. Her heart raced at the thought of just seeing something, anything, beyond drab Gishin and its surrounding fields. For once, shed taste the illusion of being free from the rules that constrained her every move. She lost herself in a daydream of what was out there, what wonders she might see in Shinroo, a town two or three times the size of Gishin.

Then she heard whispers, the words arriving as if on a cold breeze, breaking into her happy reverie:

Old Cassie was taken last night.

Iskra jerked her head around, seeking to find the speaker. She scanned the faces of the women sitting to her left on the worn wooden benches, all huddled over the meager breakfast of runny porridge and pine needle tea the village provided. The women all looked the same, garbed in shapeless, faded, and mouse-colored dresses and aprons over woolen leggings, all with hair cropped under their ears and across their foreheads. The only variations were the colored bands that circled their left sleeves at the shoulder to announce their professions.

Thats right, said a thin woman hunched over her tea. Shes gone.

Iskra noticed the womans shaking hands and pale, fearful eyes. She wondered if Cassie was someone the woman had been close to.

The words repeated themselves in Iskras mind, cramping her stomach. She stared at her half-eaten porridge, no longer hungry. Old Cassie was taken last night.

A hand grabbed her shoulder and brought her back to reality. Are you coming? Well be late.

Yes, Tavda, Iskra replied. She shook herself as if to free her mind from the fear that had gripped it and followed her friend through the crowded hall in the inn where most villagers ate their meals, since cooking was considered to be unsafe. The hall didnt seem as noisy and energetic as it had just a few moments ago. She shivered as she stepped onto the dirt street, a chilly breeze puffing in her face, making her blink. She drew her threadbare, slate-colored shawl closer.

Iskra hurried to catch up with Tavda, passing rickety wooden stalls displaying withered apples and potatoes with sprouting eyes, pottery and candles, shoes, and shawls, past people wearing their drab gray clothing. She caught up to her friend just as Tavda burst out from between the rows of stalls into what the village of Gishin called a main square. The towns monument to safety stood in its center, a statue of a man holding a sword in one hand, his other arm held out to protect an old woman and a little boy. Iskra thought the woman and the boy looked as though they didnt think the man could protect them from a cockroach. She frowned at the monument, noting it was shabby and worn down, much like the village.

Six or seven wagons were lined up to one side of the monument, some empty, others piled with the coarse earthenware made in the village, along with stacks of newly cut wood. Brown-clad traders piled goods on wagons or checked harnesses. Tavda and Iskra sprinted to the third wagon, where Tavdas mother, Revda, was negotiating with a trader.

These girls are only fifteen, Revda said, pointing to the white bands on the girls shoulders that marked them as students. Youll look after them? Revda looked hard into the mans eyes.

He smiled, his grizzled eyebrows almost completely hiding his eyes. Like they were my own granddaughters.

Revda didnt smile back. Make sure my other daughter meets them. She handed the man a few coins. Shell pay you the rest when you get there. She hugged Tavda. Im still not so sure about this.

Iskra felt her knees grow weak. If Revda didnt allow Tavda to go, her own mother was sure to forbid the trip. Shed looked forward to this excursion for weeks and winced at the thought of it being denied at this last moment.

Tavda pulled on her mothers sleeve. Mam, you promised I could visit. Well be fine. See all the guardsmen? She pointed to the opposite end of the square, where ten guardsmen wearing their dark brown leather uniforms sat on their horses. Ten men to protect us. Well have no problems on the road.

Tavdas mother pursed her lips and shook her head.

Iskra hadnt thought about the bandits known to prowl the road between Gishin and Shinroo. It just now occurred to her to wonder if going to Shinroo was such a good idea. Her mouth felt like shed eaten dust for breakfast. Her enthusiasm for travel started to evaporate like dew on a hot summer morning.

Humph. Tavdas mother scowled at the guardsmen as if she doubted their ability to protect anyone.

Besides, Tavda said, you know the candles in Shinroo are safer than the ones here. Just like the darning needles. And you did want me to try to find a new teapot.

Guardsmens cheers interrupted her answer. Kaberco, the Ephor of Gishin, strode through the market, his long black cloak swirling around him, his leathers creaking, the gold chain of his office draped over his shoulders glinting in the sun. Kaberco walked down the line of the caravan, placing his men at the front and rear of the line of wagons. He stopped when he saw Iskra.

Peace and safety, Iskra.

Peace and safety to you. She smiled at the huge man whod been like an uncle to her after her father died.

![Catalano - The great white hoax: the suppressed truth about the pharmaceutical industry [American freedom vs. medical power]](/uploads/posts/book/195943/thumbs/catalano-the-great-white-hoax-the-suppressed.jpg)

Created with Vellum

Created with Vellum