Let the conversation begin...

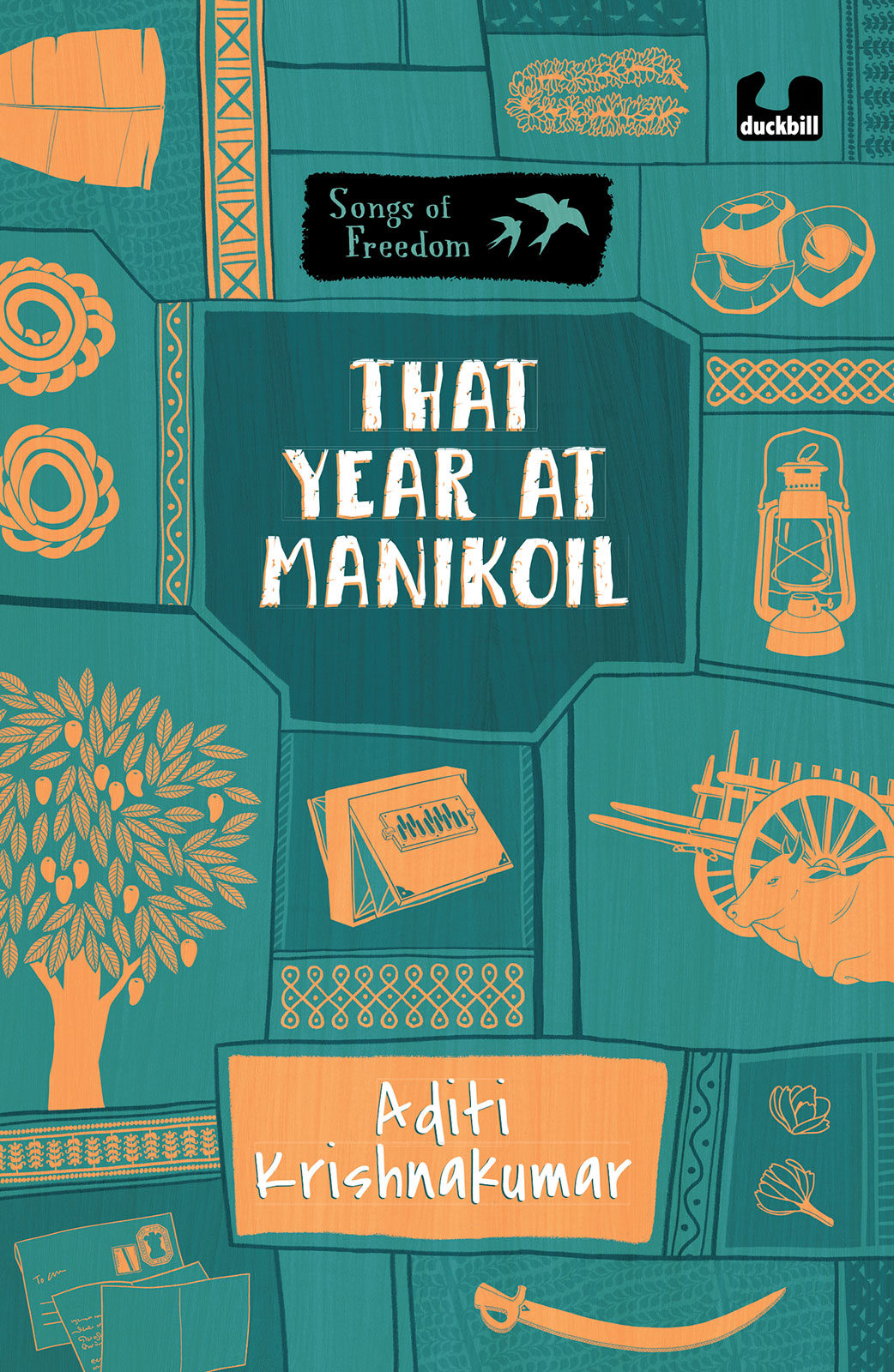

Chapter I

April 1944

On an April day when I was nine years old, I had my first inkling that my world was going to change.

I woke at dawn, as I did on most days, to the sound of my mother singing the Suprabhatam. She had excellent lungs. Her voice carried to every room of the house and edified passing traffic on the road outside. I sat up in bed, folded my hands and sang along.

This show of piety had an ulterior motive. I had my maths exam that day. With no illusions about my abilities in that direction, I was willing to take any help going, including Venkatachalapathys.

My older sisters, Vasantha and Valli, whose mattresses were already rolled up in the corner, laughed unkindly. In maths, as in most other subjects, I was the exception in my brilliant family. In class after class, I had failed to live up to the shining example set by my sisters. The expectation held by my parents, siblings and teachers was that I would continue to do so.

Vasantha, at fifteen, was a star of St Catherines and a great favourite with the principal, Sister Bridget. She was only a year away from finishing school. I, many years from that happy time, envied her, but Vasantha didnt appreciate her impending freedom. She intended to curb it by enrolling in Queen Marys College to study mathematics.

Valliproperly Kanakavalli, which was too big a mouthful for everyday usewas two years Vasanthas junior. She was famed in school for ignoring such foolish directions from examiners as, Choose any four of the following six questions. Valli chose all six and got them all correct. I knew this better than anyone, because my teachers never failed to bring it up when I chose only three and got two of them wrong.

I was four years younger than Valli. My academic abilities were far worse. Sister Bridgets excitement over Vasanthas future career was matched by Sister Irenes despair over any possibility of mine. (I hadnt yet graduated to Sister Bridget, and hoped she would take her well-earned retirement before that dark day came.)

I dont understand, Sister Irene would say, clutching her brow. Sister Irene had a flair for the dramatic. I dont understand how you can make such atrocious mistakes. Your sisters never did.

I was so used to doing all the things my sisters had never done that, on a normal day, the comparison between their academic excellence and my mediocrity was only mildly unpleasant. Exam days were different. I might plead. I might coax. I might give my parents solemn assurances that I would not in later days regret my lack of schoolgirl laurels. I didnt want to be a college principal. The examples of Marie Curie, Annie Besant and Sarojini Naidu left me cold. All I wanted was to get through my schooldays with as little trouble as possible.

It made no difference. My parents were adamant. I would go to school. I would take every exam for which Sister Irene in her optimism was willing to enter me. And I would have a respectable showing, or they would know the reason why. (In my fathers case, he meant this literally. When I brought returned exam papers home for a parental signature, Amma adopted an attitude of philosophic composure. Appa went over each paper question by question, getting to the bottom of every mistake I made in the vain hope that I would do better next time.)

Praying wont help you, Vasantha told me that day. Shed already bathed and was plaiting strings of jasmine into her hair. No exam-day nerves for her. If you have enough time to sing, you have enough time to revise.

You might think that Vasantha was being bossy because she was shortly going to be a college student. (She was also engaged to be married to the son of my fathers lawyer friend, but this was a secondary consideration. I couldnt see anyone, leave alone a mere husband, standing in my sisters way if she decided she wanted to be a college principal.) This is not true. As far as my memory stretched, I couldnt remember Vasantha passing up an opportunity to tell people what to do. She was wont to say it was the privilege of an elder sibling to instruct. If so, it was a privilege exclusive to her: she bossed around our older brothers, Gopu Anna and Kittu Anna, as freely as she did me. Some people are born givers of orders.

She doesnt have time, said Valli. The Sanskrit vadyar will be here in half an hour.

What? I yelped. Today is a free morning.

Free mornings are for people who dont mix up their verbs when Appa quizzes them. Valli gathered her bundle of clothes and went to the bathroom. Appas asked him to come every morning until hes satisfied that youre making progress.

Unaware of my horror, my mother sang on.

The Sanskrit vadyar, as befitted a teacher of languages, was a fine orator. He let himself go on the subject of my half-learnt declensions. It was in a much-chastened mood that I went to the kitchen for breakfast.

Do you have your Saraswati? Gopu Anna asked me as I took my place.

He had given me a silver medallion the previous week, having been assured by one of his friends that it was guaranteed to fill the mind of the bearer with the highest gifts of the goddess of learning. Gopu Anna had, in my memory, bought several medallions, two rings with large and (even he had admitted) ugly pieces of crystal, and a small clay demon that now resided in our backyard because Amma had refused to have it in the house. How much divine assistance he had gained through these purchases nobody knew, but he still lit an agarbatti before the demon morning and evening.

Amma didnt scoff at the medallion. Even my mother didnt dare to scoff at Saraswati. But she looked as if shed like to. Amma was the most robustly unsuperstitious person I knew.

If Raji hasnt studied, she said, scooping rice and sathamathu on to my banana leaf with a vim that boded ill for me if I hadnt, Saraswati wont help her.

At least today is the last exam, I said. Itll be a month before I have to know how I did.

Despite my words, I didnt feel like eating, although lemon ginger rasam was a favourite.