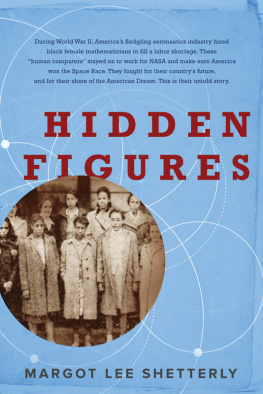

CHAPTER 1

GET THE GIRL

Everyone was watching her.

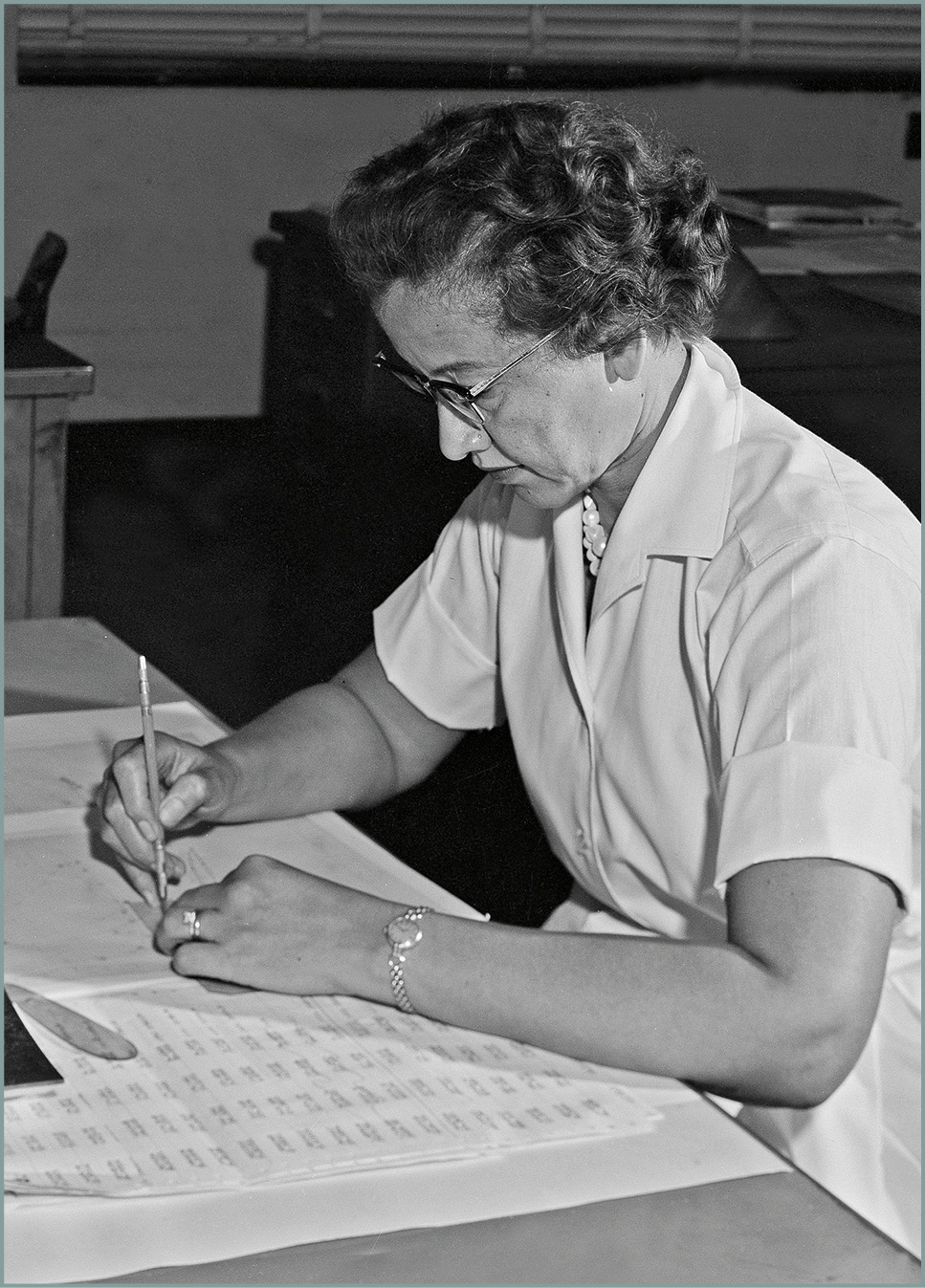

Katherine Johnson

It was a chilly morning in February 1962. Katherine Johnson glanced up from her calculations to see a crowd of anxious white men surrounding her desk. Each man was leaning forward, trying to catch a glimpse of her work. Her pencil danced across the graph paper. She jotted long strings of numbers that stretched to impossible lengths. Finally Johnsons pencil stopped. Her eyes darted across the numbers once, and then twice. With a sigh, she smiled and leaned back in her chair.

The crowd of men inside the Space Task Group office at the John Glenn would be safe to fly.

More than 850 miles away from Johnsons desk in Langley, Virginia, Glenn nervously walked across the sun-baked launch pad in Floridas Cape Canaveral.

He looked up at a towering rocket. On the very top sat a tiny metal capsule, his spaceship. Glenn was preparing to become the first American to orbit Earth. If all went well, his ship would zoom three times around the planet. It would exceed speeds of 17,000 miles per hour. That part wasnt what was bothering Glenn. He was worried about how or if he could get his ship back home.

Space flight was extremely precise. It relied on countless complex mathematical equations. If Glenn didnt direct his ship back down to Earth at the exact right moment, speed, and angle, he was doomed. His ship could bounce off Earths dense atmosphere and skip out into space. Or it would land in the wrong spot. If it didnt splash down in a deep ocean, it could be crushed upon impact.

Glenn knew that

Glenn understood that his behavior might raise red flags. NASA expected him to toe the agency line. He needed to follow orders. He needed to perform his duties. And he needed to help the United States win the race to space. It was one thing for an astronaut to ask for a double check of numbers. It was another thing entirely to ask for a black woman to do the job.

Just then, Glenn looked up. Two NASA technicians were jogging across the launch pad toward him smiling broadly. Glenn knew Katherine Johnson must have done the math. Glenn laughed quietly and looked at the sky. He was going to space.

Astronaut John Glenn orbited Earth in Friendship 7.

On February 20, 1962, John Glenn blasted off. He completed three Earth orbits before safely splashing down in the Atlantic Ocean. Glenn was celebrated as an American hero. He was the star of parades, parties, and countless news stories. One hundred thirty-five million people had watched his mission on TV.

Johnson wasnt invited to any parades. She was not the guest of honor at any fabulous parties. Few members of her own community in nearby Hampton, Virginia, even knew what she had done. None of this was terribly surprising to Johnson. She was an African-American human computer. She was used to being absolutely essential, but also unseen.

And yet And, as an added benefit, letting the human computers do the math helped the engineers spend their time dreaming up new types of spacecraft.

Johnson never complained about being ignored. She knew she was lucky to be at NASA. And though some at NASA might not admit it, the agency was lucky to have her.

Katherine Johnson was a brilliant mathematician. She was born in 1918 and grew up in a small town in West Virginia. Most of the African-American girls at that time left school after eighth grade. Becoming a professional mathematician was a career few people in her hometown pursued. But Johnson was different. She turned her passion for numbers into a vocation.

Johnson had always focused on math. She was drawn to numbers even as a young child. I counted everything, she recalled. I counted the steps to the road, the steps up to church, the number of dishes and silverware I washed anything that could be counted, I did.

Her parents and teachers recognized Johnsons talent. They encouraged the young girl to work hard. With their help, Johnson flew through school. She skipped grades to graduate high school at age 14. She graduated from West Virginia State College at age 18 with the highest honors. After college, she got married and had children. She then worked in one of the only careers available for educated women she became a teacher. Johnson enjoyed teaching, but struggled to stretch her meager paycheck. When she heard about an opportunity for black mathematicians in Virginia, she jumped at the chance. After all, it promised to pay three times her teaching salary.

In 1953 Johnson was hired at NASA, then known as the laws, a series of rules that enforced racial segregation, had been part of her life since birth.

Johnsons supervisor was a black woman named Dorothy Vaughan. She greeted her new employee and showed her to her desk. Vaughan explained Johnsons new responsibilities. Each morning Vaughan would distribute mathematical equations to her staff of computers. When they finished, the computers would turn their work in to Vaughan. She would then return it to the correct departments. Occasionally, Vaughan explained, she might send Johnson out to a specific department to do on-site calculations.

Just two weeks after Johnson started in West Area Computing, Vaughan handed her an on-site assignment. She would be helping calculate numbers for the Flight Research Division. The engineers in this division were some of the agencys smartest. They worked on incredibly complex problems. Their math took them to the cutting edge of aeronautics.

As a black woman, Johnson at first met some resistance from her white coworkers. On her first day, Johnson smiled at the white man working next to her. He just walked away. But she came to get along very well with her white male coworkers. They appreciated her curiosity and intelligence. Johnson loved how much they loved their jobs. She even adopted their morning ritual. She would get a cup of coffee, sit at her desk, and read through the daily newspapers and aviation journals. She scanned them for new information about advancements in the aerospace industry. Any news she spotted in the papers might affect her work. Johnsons colleagues noticed her commitment and drive. They stopping thinking about her as a colored computer. Now they simply thought of her as Katherine.

Johnson was delighted to have found such a challenging workplace. After years of searching, she knew she had landed in the right spot. NACA appreciated her efforts and gave her a place to thrive. But the Flight Research Division wouldnt be the end of Johnsons story. Her work there would later land her a coveted seat in the Space Task Group the division charged with winning the space race.

CHAPTER 2

THE SPACE RACE

Katherine Johnson wasnt the first black woman to find a bright future in the stars. Black slaves had studied the constellations for centuries. They etched the North Star into their brains. Enslaved people could follow this beacon out of the South. If they were lucky enough, they might even follow it to freedom.

Slavery had been abolished in the United States for nearly 100 years when Johnson helped send John Glenn into space. But life for black Americans was still very hard. Many white Americans held onto old beliefs. They thought that black people were inferior. Reminders of the way black people had been treated in American history were everywhere. Even the space-age campus at Langley could not escape the past. It was built on land that had once been a slaves.