SCRIBNER

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

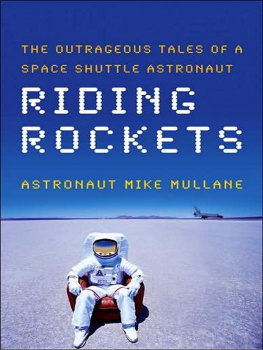

Copyright 2006 by Mike Mullane

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

SCRIBNER and design are trademarks of Macmillan Library Reference USA, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, the publisher of this work.

DESIGNED BY ERICH HOBBING

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

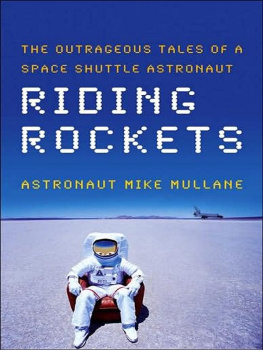

Mullane, R. Mike.

Riding rockets: the outrageous tales of a space shuttle astronaut/Mike Mullane.

p. cm.

1. Mullane, R. Mike. 2. AstronautsUnited StatesBiography.

3. Space Shuttle Program (U.S.) I. Title.

TL789.85.M86A3 2006

629.450092dc22

[B]

2005056123

ISBN-13: 978-0-7432-9676-2

ISBN-10: 0-7432-9676-1

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com

To my mother and father, who lifted my eyes to space.

To the thousands of men and women of the space shuttle team,

who put me in space.

To Donna, who was at my side every step of the way.

Contents

Acknowledgments

My first and greatest thanks go to my wife, Donna, for her patient and loving support during my writing of this book. My children, Patrick, Amy, and Laura, were also enthusiastic cheerleaders. Thanks!

I am deeply grateful to my agent, Faith Hamlin, of Sanford J. Green-burger Associates, who convinced me to write the story of my life. Thanks, Faith, for holding my hand and so passionately representing Riding Rockets.

My Scribner editor, Brant Rumble, poured his exceptional talents into my story and I am indebted to him. Not only did he make me a better writer, he was my number-one fan throughout the publishing process. Also, a heartfelt thanks to the rest of the outstanding Scribner team who had a part in bringing my story to print.

Johnson Space Center Flight Director Jay Greene was the first to read my manuscript and I am thankful for his insight. Thanks also to astronauts Robert Hoot Gibson, Rhea Seddon, Mike Coats, Pierre Thuot, and Dale Gardner, who took time from their busy schedules to proof my work. In making these acknowledgments, I am not implying these reviewers agreed with everything I wrote. One thought that I was too hard on the politician astronauts. Another felt that I wasnt severe enough in my criticism of some key NASA managers. While I appreciate all of their opinions, I did not modify my story to accommodate them. Riding Rockets is my story created from my memories.

Many of the conversations I relate in the book are decades old. For that reason, the quotation marks should not be construed as enclosing verbatim dialogue. Rather, they contain my recollection of those discussions.

Chapter 1

Bowels and Brains

I was naked, lying on my side on a table in the NASA Flight Medicine Clinic bathroom, probing at my rear end with the nozzle of an enema. Welcome to the astronaut selection process, I thought. It was October 25, 1977. I was one of about twenty men and women undergoing the three-day physical examination and personal interview process that were part of astronaut candidate screening. Almost a year earlier NASA had announced they would begin accepting applications for the first group of space shuttle astronauts. Eight thousand had been submitted. NASA had whittled that pile to about two hundred, a cut I had miraculously made. Over successive weeks all two hundred of us would eventually find ourselves on this same gurney probing at our nether regions as we prepared for our bowel exam.

It was rumored NASA would select about thirty from this group to fly the shuttle. The odds were long that I would be among that blessed few. Not that I wasnt qualified. I had all the squares checked. I was a West Pointer who had taken a commission in the air force. I wasnt a pilot. My eyesight had been too bad for that job. But I had nearly 1,500 flying hours in the backseat of RF-4C aircraft, the reconnaissance version of the F-4 Phantom. Like Goose from Top Gun, I was the guy in back. In my ten-year career I was a veteran of 134 combat missions in Vietnam, had completed a masters degree in aeronautical engineering, and was a graduate of the Flight Test Engineer course taught by the USAF Test Pilot School. I was most certainly qualified, but so were a few hundred other applicants. I had been around too many super-achieving military aviators to fool myself. While I might have had a little of the Right Stuff, there were legions of others who had it in abundance, pilots who would make the likes of Alan Shepard and John Glenn look like candy-asses.

Yes, the odds were long, but I was going to give it my best shot. At the moment that best shot was aimed squarely at where the sun didnt shine. I was in the process of preparing for my first proctosigmoidoscopy.

Just before I entered the bathroom I overheard one of the civilian candidates lamenting that he had failed his procto-prep. At the word failed my ears perked up. He had skimped in his bowel-cleansing efforts and would have to repeat his test tomorrow.

FAILED PROCTO-PREP . I could imagine those words in big red letters on the mans physical report. Who would see them? Would they count in the selection process? When a selection committee was picking one person in seven and each was a superman or a wonder woman, you didnt want to have the word failed anywhere, even in reference to something as innocuous as a procto-prep. My paranoia in this regard was fueled by a military aviators deathly fear of the flight surgeon. When his stethoscope came to your chest or that blood pressure needle was bouncing, it was your career on the line. A little blip and you could leave your wings on the table. Military aviators looked forward to a physical exam about as much as they looked forward to an in-flight engine fire. We didnt want failed on any document concerning anything that came out of a flight surgeons office. I had known pilots who would secretly visit a civilian off-base doctor for some malady rather than bring it to the attention of a flight surgeon. This had been strictly forbidden, but the only crime was to get caught. I employed the same logic on the flight to Houston for this medical test. In an act of incredible navet, the docs at NASA had asked us to hand-carry our medical records from our home bases. This was akin to trusting a politician with a ballot box. As the miles passed, I pulled out pages I felt could generate questions I didnt want to answer. In particular I pulled out references to the severe whiplash I had suffered during an ejection from an F-111 fighter-bomber a year earlier. During that incident my helmet-weighted head had snapped around as if it had been on the tip of a cracking bullwhip. My neck had been badly hyperextended. After a week of wearing a neck brace, the Eglin Air Force Base (AFB) doctors returned me to flight, but I wondered how the neck injury would be viewed by NASAs docs. Certainly it couldnt help me. It was the type of questionable injury that could draw a disqualified stamp on my application. In all likelihood there would be 199 other applicants without a history of neck injuries. I wasnt going to take a chance. I liberated the offending pages from my files, planning to reinsert them on the return flight. I had one very slim chance of getting selected as an astronaut. I wasnt going to let a little thing like a felony get in the way. I would alter official government records and, like countless other aviators before, hope I didnt get caught.

Next page