This book is a memoir. It reflects the authors

present recollections of experiences over time, which

are fallible. Memories are not to be treated as fact;

rather, they are an interpretation. Some names and

characteristics have been changed, some events

have been compressed, and some dialogue has been

recreated. There are no bad people in this book and no

victims. There are only people, and their impression on

the author is subject, like everything else, to bias.

Copyright 2022 Rachael Finley

First edition, 2022

All rights reserved.

Written and Recollected by Rachael Steak Finley

Edited by Tia Harestad

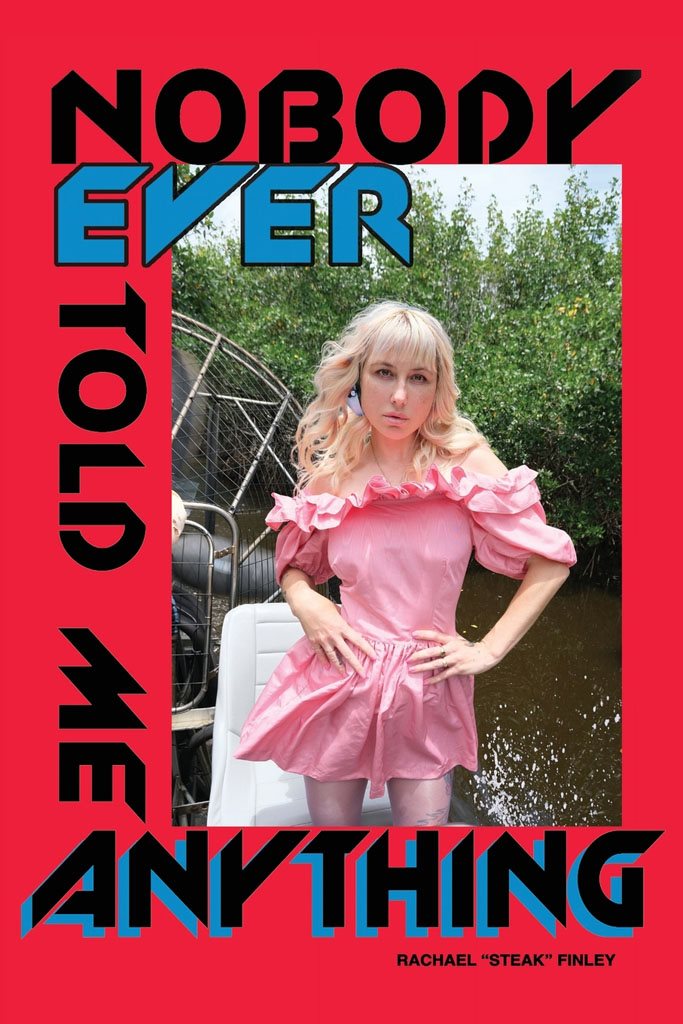

Cover Photo by Zak Quiram

Interior Layout and Typesetting by Lizette Chavez

For my flat tire friends, for Mars, who is my whole world, for Liz.

For Joe, Josephine, Skip, and Hannah. I had to take you out because of page count but youre always here.

For the people who have loved me along the way.

For the Internet community who brought me Tia, who helped make this possible.

For the help of people like Shannon Byrnes, M.A. LMFT, thank you.

For Zak. For loving me through all of it and encouraging my evolution.

For my Mom, and for every version of myself that came before today.

Introduction

I dont have the authority to tell you that there are more ways to die in Florida than anywhere else in the United States, but what I can say is that it feels like there are.

Venomous spiders, alligators; pet pythons let loose in the swamp, the people who hunt them with revolvers for government change. In Florida, the only thing that looms larger than death is the sky. Mercurial. Blue, to thunder-struck gray. And even it can, you know, kill you. It was underneath those clouds that I met Rachael for the first time.

I dont want you to tell me what you think until the end.

I didnt know whether she was talking about her hometown or quoting our first phone conversation after she sent me her book, but there was a cheeky, inimitable grin splitting her face. We were standing the distance of her trucks front bumper apart, each of us unsure of the others COVID-19 comfort level, but slowly inching forward in the way that people with a shared secret do. The way that everyone does around Rachael.

Shes disarmingly honest, easy to talk to, sincere. All of the things youd want in an advice columnist, and then some. For one, she doesnt call herself a columnist. She wont even call herself a writer.

I just want this story to live somewhere else. A place where I dont have to feed it every day, but where it can feed other people. You know?

I told her that I did know. And, that it was a pretty writerly thing to say.

The thing with Rachael, with Nobody Ever Told Me Anything, and with all of us is, is that no matter how self-possessed, satisfied, or successful we may seem, there is a version of ourselves that wed like to forget. A skin weve shed. There are those who spend their entire lives trying to destroy this link to the reptilian world, and those who embrace it. People who, like the gecko, swallow their shed wholenot as a means of hiding their former self, but in order to nourish their present.

In a way, Nobody Ever Told Me Anything is this digestive process. There are few people who have lived as many lives as its author (foster child, cancer survivor, designer, television hostthe list goes on) and even less willing to examine those lives up close. By sharing her story, Rachael doesnt just teach you how to reconcile with your past or the people in it, or open her decisions up to speculationshe grants her readers the same unique privilege she always has, from Tumblr to podcast to Hot Lava, even when it was so often missing from her own life. Safety. To share and to learn, and share so that others might not have to learn the hard way.

Rachael did that for me in Florida. She showed me where to step, how to spot sandspurs, promised to look out for sharks when I jumped in the water, and pointed which way to run on the golf course in the dark (yes, that golf course). For someone who claimed to have never been told anything, she seemed to have an answer for every danger. Was it an act, this unknowing? Or, was it the only way to respond to knowledge of her kind?

Ive followed Rachael in her backyard, and Id follow her in places shes never been. She is that kind of presence, that kind of writer, that kind of friend. I dont believe she will ever be in her final form; I think she is the kind of reptile that was born to disrupt.

Tia Harestad

June, 1996

Rachael, get up.

Rachael, up. Now.

I hear the urgency in my Moms voice and my eyes snap open. I prop up on my elbow.

What is it?

Mom doesnt respond, but I feel her opening drawers, shifting things. I hear a few coins clatter together in her palm and turn to the window to see if its still dark out. The shades are black, but the shades are always black because were not allowed to open them, so that doesnt help.

What time is it? I ask.

Im trying to get my bearings, blinking through the shadowy shapes, scanning the room for anything out of order. Once my eyes adjust, I see that Mom is already dressed. In fact, shes showered, her hair set in tight curlers. She has a squiggly brown line drawn and caked around her eyes. She looks okay. Shes breathing, shes present. Theres a tinge of happiness and a lot of hurry on her face, and it makes me feel uneasy. I try to look unsurprised, wondering how she managed to get ready without me noticing that she left the bed or turned on the shower. I feel guilty for sleeping, like I missed something important.

Then, she leaves the room and I leap up, chasing after her as she flits about the house checking vessels for loose change.

Where are we going?

Mom doesnt say anything, so I listen to her body, her movements. She holds out her fist and hands me her credit cards, motioning for me to follow her to the kitchen. I see her duffel bag and a pair of shoes against the front door as we walk past. The kitchen is slightly brighter than the bedroom, an early, grayish light pushing against the shades. Mom points a shaking, sloppily painted finger to a bright blue piece of paper, taped crookedly on the wall.

Emergency numbers, she mumbles, reading through them.

I nod, acknowledging the same old suspects: my grandma, my aunt, the number for the hospital, poison control, and Moms friend, Ms. Kilroy, one of the other teachers at school. Her name is at the top of the list, circled in red ink.

Ah, an ally, I think to myself.

You call her first, Mom says. Then dont call anyone else unless youre dying.

It dawns on me that these are the first instructions of their kind, ever.

When Mom leaves, she doesnt usually make an announcement, or even acknowledge that shes left; the click of the door, or the distant sound of her high-heeled footsteps, are the only things that tell me Im alone. But here, in the kitchen, shes giving me a list of contacts, pushing her cards at me, telling me where I can find the wads of cash she keeps hidden around the house.

Where are you going? I ask, finally.

Mom leans down to speak with me. Her uneven eyeliner gives her tired eyes a look of surprise.

Rach, Mom is very sick.

I nod. Of course shes sick. This is old news to me. Weve been discussing her sicknesses my entire life. Its why she lays on the couch with her headaches, why she sometimes throws up and needs to be alone in her room. I am comfortable with sick. In fact, I think its great, because it requires no preparation from either of us.