Contents

Guide

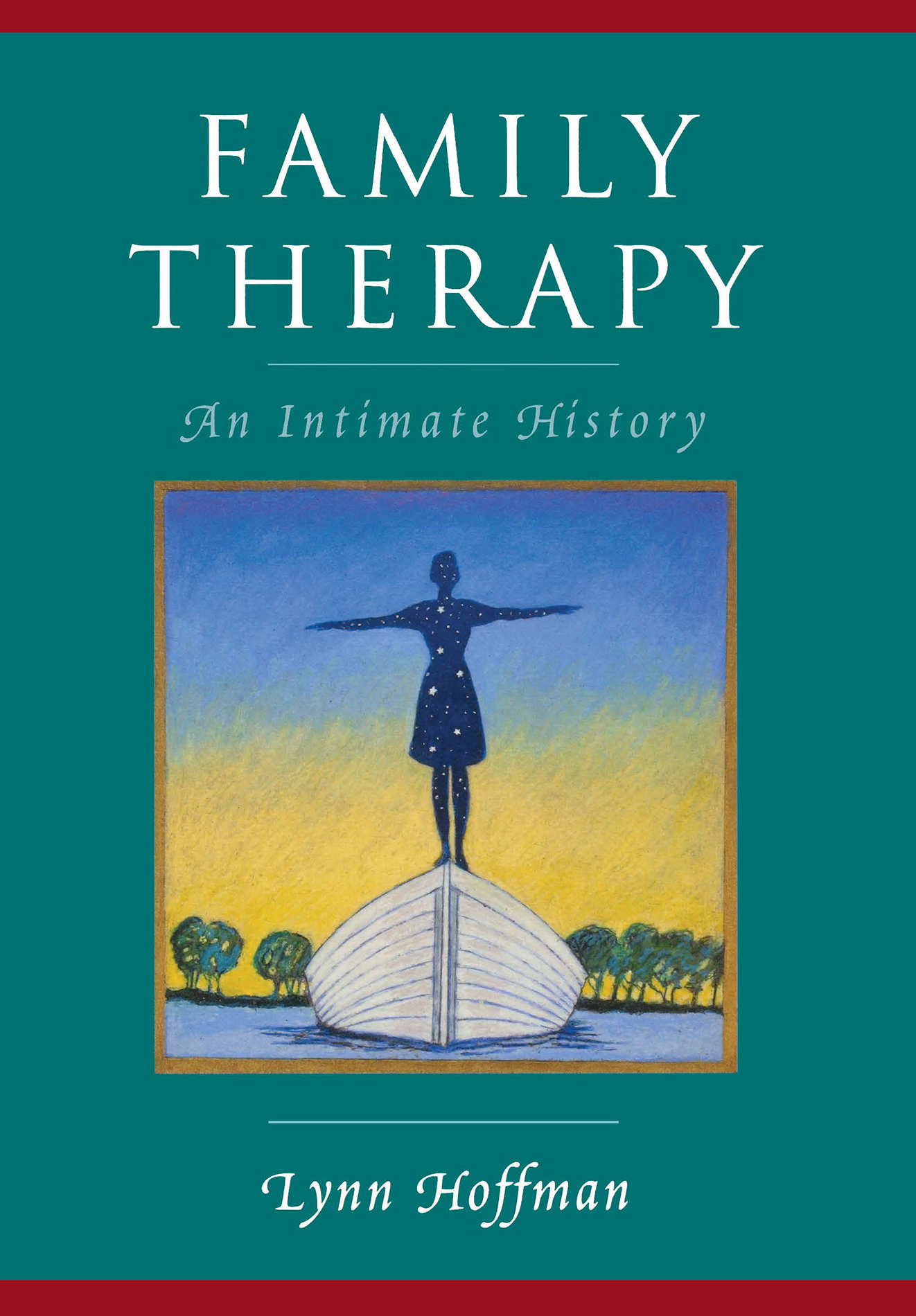

BOOKS BY LYNN HOFFMAN

1968: Techniques of Family Therapy (with Jay Haley)

1981: Foundations of Family Therapy

1987: Milan Systemic Family Therapy (with L. Boscolo, G. Cecchin, and P. Penn)

1993: Exchanging Voices: A Collaborative Approach to Family Therapy

A NORTON PROFESSIONAL BOOK

FAMILY THERAPY

AN INTIMATE HISTORY

LYNN HOFFMAN

W.W. Norton & Company

New York London

Copyright 2002 by Lynn Hoffman

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Composition and book design by Ecomlinks, Inc.

Production Manager: Leeann Graham

Jacket Design: Lauren Graessle

Jacket illustration: Cooper Edens, 1987

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Hoffman, Lynn.

Family therapy: an intimate history/Lynn Hoffman.

p. cm.

A Norton professional book.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN: 978-0-393-70380-1

1. Family psycholotherapy. I. Title.

RC488.5 .H599 2001

616.89156--dc21 200104431

W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W.W. Norton & Company, Ltd., Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1 T 3QT

To My Family

Contents

Acknowledgments

How does one acknowledge an entire field? I feel that my book represents a great cloud of witnesses, as it says in the Bible: pioneering psychotherapists who insisted on working against our most persistent illusion, the stand-alone self. I wanted particularly to honor three people who are no longer with us: Virginia Satir, whose boldness started me off, E.H. Auerswald, who offered me protection along the way, and Harry Goolishian, who drew me into his enthusiasm for postmodern ideas. I also acknowledge my debt to the mentors who led me through difficult terrain, and the families and couples who helped me to critique my own myths. This book is composed of their stories. In a way, it is a version of my earlier book, Foundations of Family Therapy , except that it is written from a much more personal point of view.

How does one acknowledge an entire field? I feel that my book represents a great cloud of witnesses, as it says in the Bible: pioneering psychotherapists who insisted on working against our most persistent illusion, the stand-alone self. I wanted particularly to honor three people who are no longer with us: Virginia Satir, whose boldness started me off, E.H. Auerswald, who offered me protection along the way, and Harry Goolishian, who drew me into his enthusiasm for postmodern ideas. I also acknowledge my debt to the mentors who led me through difficult terrain, and the families and couples who helped me to critique my own myths. This book is composed of their stories. In a way, it is a version of my earlier book, Foundations of Family Therapy , except that it is written from a much more personal point of view.

Thanks also to Mary and Kenneth Gergen and Sheila McNamee for their encouragement, and to Mary Catherine Bateson for her inspiring example. I must also mention the American Society of Cybernetics, which has continued Batesons tradition of inquiry under the aegis of its three wise men: Heinz von Foerster, Humberto Maturana, and Ernst von Glasersfeld. Other inspirers include artist Richard Baldwin, who was a longtime partner in unorthodoxy; Cathy Taylor and the MOSAIC mothers; Michael White, a tender therapist but a tough theorist; and Tom Andersen, Peggy Penn, and Judith Davis, wonderful practitioners, beloved colleagues, and unfailing friends. Readers of this book will meet many other unusual talents who contributed to my education. An alternative subtitle for the book would be A Family Therapist Learns How.

As for the people in publishing who helped me, I want to thank Jo Ann Miller for keeping a place at the table for me at Basic Books until that place expired, and Susan Munro, who led me to Norton, was my editor. As for the process of putting the book into print, let me thank Professional Books director Deborah Malmud, associate editor Regina Dahlgren Ardini, and editorial assistant Anne Hellman, who have managed to compress the bookmaking time to a fast six months. I also want to thank my writer friend Jane OReilly for leading me to computer wizard Craig Smith, who created the original idea for the cover design, and poet/painter Cooper Edens, who gave permission to use one of his pictures.

Lastly, I want to thank my daughters, Martha and Livia Hoffman, who read parts of the manuscript and gave me good advice, and my ex-husband, Ted Hoffman, for his unceasing moral support. I have one more daughter, Joanna, who is estranged from me, but her clear spirit lives at the heart of this book and gives me hope.

Lynn Hoffman, Northampton, Mass.

Introduction

My Mothers Ashes

This book traces my journey from an instrumental, causal approach to family therapy to a collaborative, communal one. When I first became acquainted with the field in 1963, I assumed that a therapist was supposed to fix a system that was in trouble. Over the course of time, the description of the problem changed from a maladaptive behavior to a dysfunctional family structure to an outmoded belief. In all these cases, however, the therapist placed herself outside the arrangement in question. This assumption of objectivity led to a therapist stance that was aloof and distancing, but it was congruent with the rational, scientific norms of the day.

This book traces my journey from an instrumental, causal approach to family therapy to a collaborative, communal one. When I first became acquainted with the field in 1963, I assumed that a therapist was supposed to fix a system that was in trouble. Over the course of time, the description of the problem changed from a maladaptive behavior to a dysfunctional family structure to an outmoded belief. In all these cases, however, the therapist placed herself outside the arrangement in question. This assumption of objectivity led to a therapist stance that was aloof and distancing, but it was congruent with the rational, scientific norms of the day.

By the seventies, I became aware of a shift in the zeitgeist. Anthropologist Gregory Bateson (1972) had already cast aspersions on the Newtonian mind-set, with its dreams of controlling the physical universe. Cognitive researchers like Humberto Maturana, Heinz von Foerster, and Ernst von Glasersfeld went on to challenge the idea that we can ever know what is really out there, because our perceptions are filtered through the sensory screens of the nervous system. Paul Watzlawick (1984), one of the early researchers in family communication, summed up this situation by describing the knower as the pilot of a ship that is navigating a difficult channel at night. If he gets through successfully, he does not know what was really there, only that he has not hit a rock.

By the eighties, this skepticism was amplified by an intellectual movement called postmodernism that had a long history in European thought. Its adherents were a brilliant group of linguists and literary critics that were influenced by philosophers Ludwig Wittgenstein (1953), Jacques Derrida (1978), Michel Foucault (1972), and Jean-Francois Lyotard (1984). Put all together, the effect of these writers work was to undermine the truth claims of philosophy, the objective standards of science, and the assumptions of social and psychological research. The postmodernists accused the modernists of believing in totalizing truths and grand narratives. The modernists declared their opponents to be relativists without values. The quarrel spilled over from the academy into other fields, including family therapy, where it created much argument but also an explosion of new energy and ideas.

Meanwhile, out in the real world that some of us no longer believed in, family therapy was losing its borders and becoming a goal-oriented, shortterm type of work. The managed care movement, with its demands for accountability, had pushed the field up against the wall. Our research results, although not any worse than other brands of therapy (Shadish, Ragsdale, & Glaser, 1995), were not outstanding, in part because our approaches had not emphasized outcome. Despite years of experimentation, family therapy had reached no firm conclusions and seemed mainly fortified by the assumptions of popular psychology and the loyalties of small believing bands. I was shocked when, as recently as 1994, I began taking one of the new drugs that alter serotonin levels and experienced immediate and lasting relief from catastrophic fears that had crippled me throughout my entire life.

How does one acknowledge an entire field? I feel that my book represents a great cloud of witnesses, as it says in the Bible: pioneering psychotherapists who insisted on working against our most persistent illusion, the stand-alone self. I wanted particularly to honor three people who are no longer with us: Virginia Satir, whose boldness started me off, E.H. Auerswald, who offered me protection along the way, and Harry Goolishian, who drew me into his enthusiasm for postmodern ideas. I also acknowledge my debt to the mentors who led me through difficult terrain, and the families and couples who helped me to critique my own myths. This book is composed of their stories. In a way, it is a version of my earlier book, Foundations of Family Therapy , except that it is written from a much more personal point of view.

How does one acknowledge an entire field? I feel that my book represents a great cloud of witnesses, as it says in the Bible: pioneering psychotherapists who insisted on working against our most persistent illusion, the stand-alone self. I wanted particularly to honor three people who are no longer with us: Virginia Satir, whose boldness started me off, E.H. Auerswald, who offered me protection along the way, and Harry Goolishian, who drew me into his enthusiasm for postmodern ideas. I also acknowledge my debt to the mentors who led me through difficult terrain, and the families and couples who helped me to critique my own myths. This book is composed of their stories. In a way, it is a version of my earlier book, Foundations of Family Therapy , except that it is written from a much more personal point of view.