FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO 78 A.D.

EARLY PALOLITHIC AGE

To understand thoroughly the evolution of Costume it is necessary to go back many hundred thousand years before the Christian era to that period in the worlds history called the

PLEISTOCENE AGE (River Beds)

or the beginning of the Early Palxolithic Age, when mankind was emerging from his earlier stage of ape.

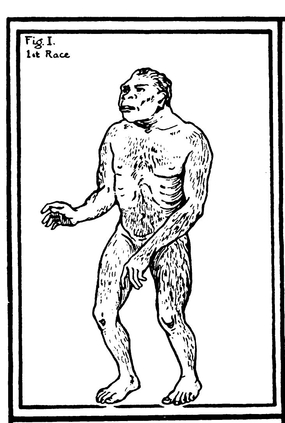

The first race of Man ( circa 550,000 B.C.) is called the Pithecanthropos Erectus, or Ape Man ( see ). They were powerfully built individuals, with low foreheads, prominent bony ridges above the eyes, and retreating chins. Their forearms were heavy and clumsy, their thigh-bones bent and their shin-bones short, so they must have been bow-legged and awkward in gait. This type of human being became differentiated from animals because development of the faculty of primitive speech enabled them to sustain thought and created memory.

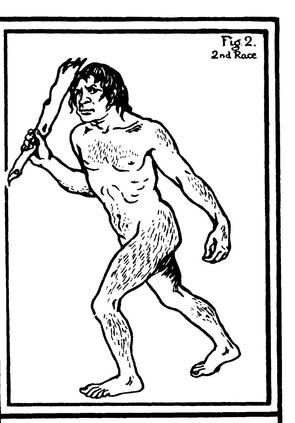

A second race of Subman, named Eoanthropos or Dawn Man, was in existence ( circa ) 110,000 B.C. Their only weapons were branches torn from the trees ( see ).

A third race, also Subman, Neanderthal Type, existed approximately 50,000 B.C. These people lived in caves and under the shelter of rock ledges. Their implements were made by chipping flints and stones into required shapes.

No clothing of any kind was worn by this still subhuman, half-animal people: not even the skins of animals, for they had not acquired sufficient skill to utilise them.

The taming of animals had not yet begun. Man was still at war with the creatures that inhabited his savage surroundings; his potential friends and servants he regarded merely as food, and most animals were classified in this simple manner. They were there to contribute to his physical support, by providing flesh, blood and the marrow of their bones, to satisfy his appetite. Self-preservation, and, later, the business of food-getting, developed mans skill as a hunter; and his skill was essentially a mental quality, for he planned the destruction of beasts that were physically infinitely superior to him.

Pits and snares were his counter to teeth and claws; and such primitive mental efforts developed the power, and ultimately increased the scope and outlook of the early men of those far-away times, laying the foundation of primitive culture and opening up possibilities of progress. Reliance on instinct was replaced by definitely constructive mental effort, and thought progressed. Thought widened racial experience.

THE LATE PALOLITHIC AGE OR OLD STONE AGE

Circa 35,000-15,000 B.C. This date, 35,000 B.C., is given as the end of the Early Palolithic Age and beginning of the Late Palolithic Age.

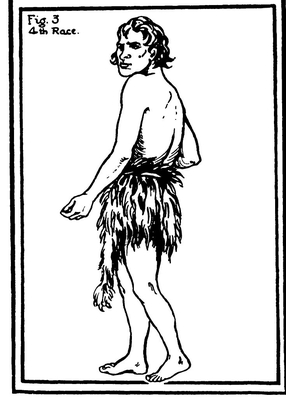

A fourth race, the Cro Magnon or True Man Type ( see ), lived during this period, and was akin to the Eskimo of the present day. These people occupied the cave-dwellings of their predecessors, but led a much freer life in the open.

First sense of art. Even in these wild and crude surroundings, a dawning appreciation of the embellishments of life is apparent in the carving and decoration of weapons and implements still extant; and, as seen in cave wall paintings, indicates a distinct sense of beauty, and the ability to copy beauty in nature.

Garments. During the whole of this period, weaving was entirely unknown. Garments, when worn, consisted of the skins of animals wrapped round the body of the wearer.

THE NEOLITHIC OR NEW STONE AGE: Circa 10,000 B.C.

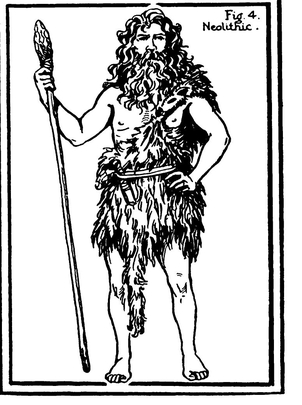

The people of this period constituted a fifth race of mankind, of moderate stature and slender proportions. Those who resided on the western side of the island now known as Great Britain were dark, and of the Iberian type. Those on the eastern side were fair, and very like the Gauls ( see ).

. A man of the Palolithic Age (first race)

. A man of the same (second race)

rig. 3. A man of the same (fourth race)

. A man of the Neolithic Age

Arms and weapons . Flints and other hard stones, worked into fine points and edges by a process of chipping, formed the spear-heads and knife-blades with which these prehistoric warriors fought their adversaries and hunted their prey.

The spear-heads were bound by thongs of hide to strong wooden poles. Axe-heads, with holes for their hafts, were treated in the same way. The knife-blades had holes worked into them, and were fastened to wooden or bone handles by wooden pegs ( see ).

Javelin-heads were made of horn, either with smooth, sharp edges finishing in a point, or barbed in several places. These were bound to poles by threads of sinew.

Bows and arrows were extensively used, especially in the chase. Arrow-heads were very skilfully shaped out of flint and bone, with grooves for fastening them on to the shafts. It is even suggested that these people poisoned their arrows, as grooves, apparently for that purpose, have been found in some of them.

In the later Stone Age, spear-heads, knife-blades, and so forth, were no longer sharpened merely by chipping, but by grinding, and finished off with a polish, and were made in various technically perfect forms. Suitable handles were regarded as especially important, and the stone implements were provided with a hole, notch or groove for fixing.

Dwellings. This race made dwellings by digging pits. The earth was thrown up all round, forming a small breastwork. In the centre of the pit a stout upright, or branch of a tree, was raised, and this supported other branches, radiating from the centre to the top of the mound to form a roof, which was covered or thatched with bracken, twigs, etc., and often covered with earth. From the outside these pit-huts had the appearance of molehills. The burying places (tumuli) were similar in outward appearance. The more important tumuli enclosed chambers built of colossal blocks of stone piled one upon another, and these were the temples, as well as the burying places, of these prehistoric people. The admirable construction of these tumuli proves that the builders of the time were little less dexterous than the Egyptians in transporting and piling masses of stone.