Contents

Clyde to Orkney

I made plenty of mistakes learning the craft of sailing but the boats themselves looked after me. Thus I can now retell the tales they brought me to. Thanks to my family and friends for their understanding and to all those who have shared stories, the personal as well as those that have been handed down.

Thanks also to all involved with an Sulaire Trust, which maintained the vessel of that name until recently, and to Falmadair, the North Lewis Maritime Trust, who continue to maintain Jubilee, Broad Bay and now also an Sulaire.

Priseact nan Ealan matched funds from The Heritage Lottery Funds interpretation budget for Lobht nan Seol (The Sail Loft) renovation to contribute towards the restoration of sgoth Jubilee

The voyages described could not have been made without the huge number of volunteer hours that go into the upkeep of these historic vessels. The generosity of individual boatowners and skippers made other voyages possible.

Sometimes I was able to return to the settings of the stories, on sea and land, to explore further. I am very grateful to the Cape Farewell project and to the skipper and crew of Song of the Whale for the chance to explore the Monachs again. Some of my descriptions, in verse, were made during the Scottish Islands 2011 project. Scientists and artists went to sea together, with a view to exploring the issue of climate change by looking closely at effects in island locations: (www.capefarewell.com/2011expedition/about/).

I would also like to acknowledge a storytelling residency from Orkney Islands Council; a Reader in Residence post (Book Trust Scotland and Western Isles Libraries); support from Creative Scotland; Peter Urpeth at Emergents, who commissioned detailed readers reports from Tom Lowenstein; the Scottish Storytelling Centre; the Scottish Poetry Library; the School of Scottish Studies (University of Edinburgh). My agent, Jenny Brown, held faith in this project as it developed and the understanding of my other publishers, The History Press and Saraband, is appreciated. Sara Hunt, publisher of my novel with Saraband, also helped me by her belief in this project, at an earlier stage.

Thanks to my companions on these voyages for their help, their company and for looking over these accounts for accuracy. Angus Murdo Macleod read a draft to comment from a mariners viewpoint. Christine Morrison put an incalculable number of hours into the detailed editing of this book through several drafts.

Earlier versions of some of the stories were shared on Isles FM radio and in Events (Lewis and Harris).

Its just not possible to mention by name all the makers and storytellers who infl uenced this book. But one person has made me think about both structures and stories more than any other. Calum Stealag, the Stornoway blacksmith, has made parts for several of the vessels described in these pages. He draws with chalk on sheet metal and breathes fi re and wit into a host of stories.

As director of Faclan festival, Roddy Murray invited me to introduce and interview Tim Severin and Helen Macdonald who have set an example in non-fiction writing. The same festival has brought me to the work of Henry Marsh and Gavin Francis, which has inspired me.

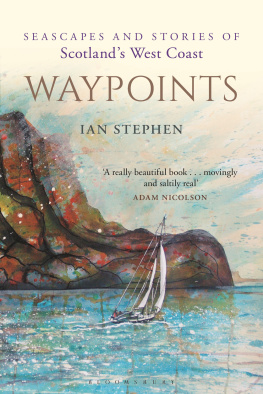

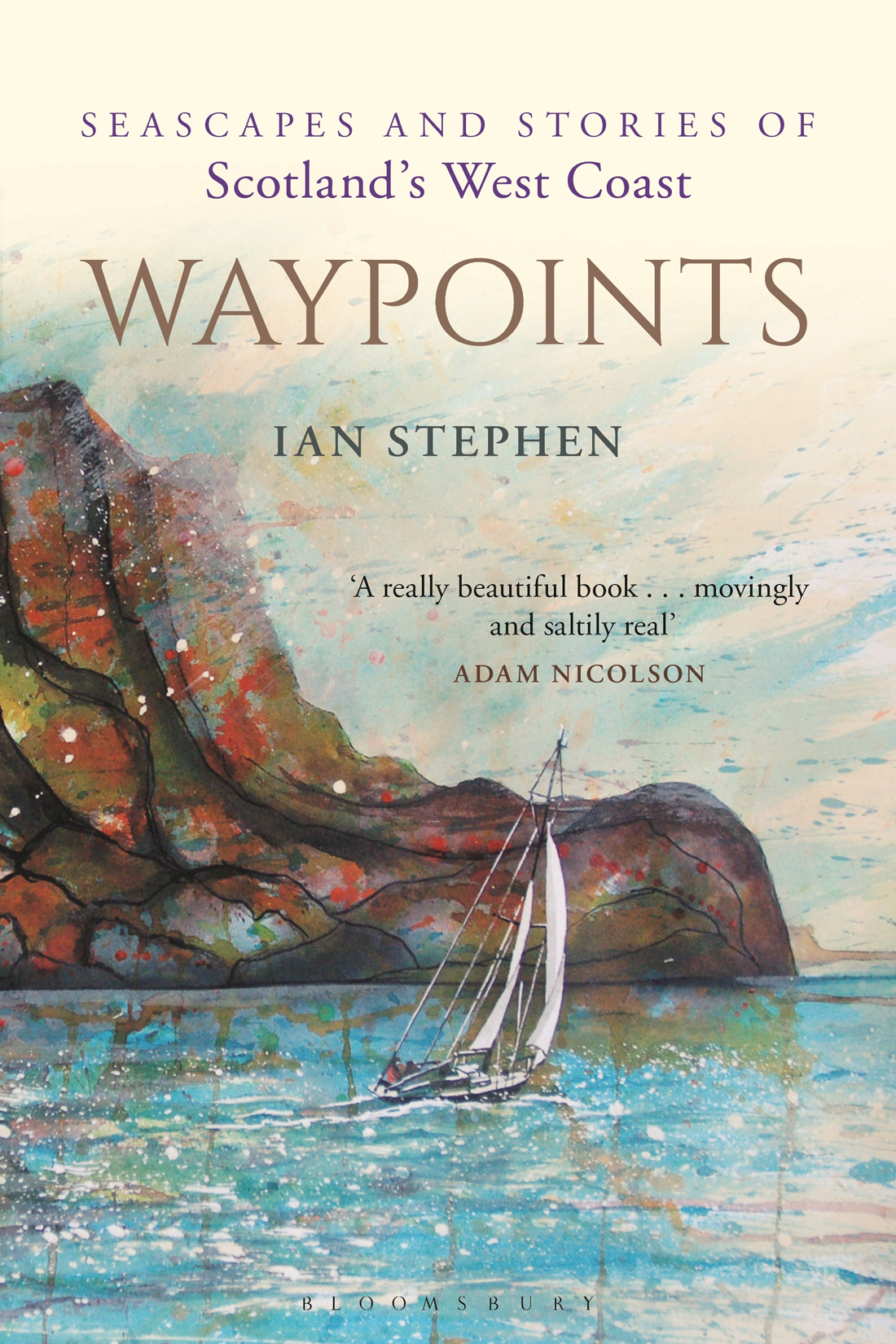

Working with all at Bloomsbury has proved a pleasure. The collaboration with Christine Morrison continues to be a joy. Our practice is on www.stephenmorrison.org.

Her individual work can be viewed at www.christinemorrison.co.uk.

The stories, retold, are:

Brown Alan

The Blue Men of the Stream

Sons and their Fathers

The Girl who Dreamed the Song

In the Tailors House

The Great Snowball

Macphees Black Dog

Ladys Rock

A Cow and Boat Tale

The Waterhorse

Black John of the Driven Snow

An Incident Remembered

The Tale of the Flounder

Chaluim Cille and the Flounder

The Five Sisters

The King of Lochlinns Daughter

The Crop-haired Freckled Lass

The Sealskin

The Two Brothers

The Lost Daughter

You could no longer cross Stornoway harbour on the decks of moored black boats but the older people always talked about being able to do that. You grew up with the names of surviving vessels, in decorated scripts. Lilac and Daffodil were drifters their black cotton nets were held up by tarred lines, punctuated with floats of pale, round cork. Then came the trawlers. Girl Norma , Braes of Garry , Ivy Rose and Golden Sheaf shed long nets on to the pier, to be mended with hard orange line from yellow plastic netting needles.

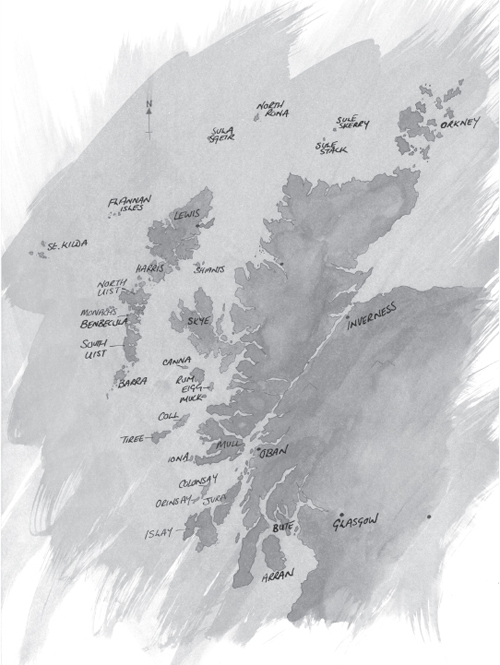

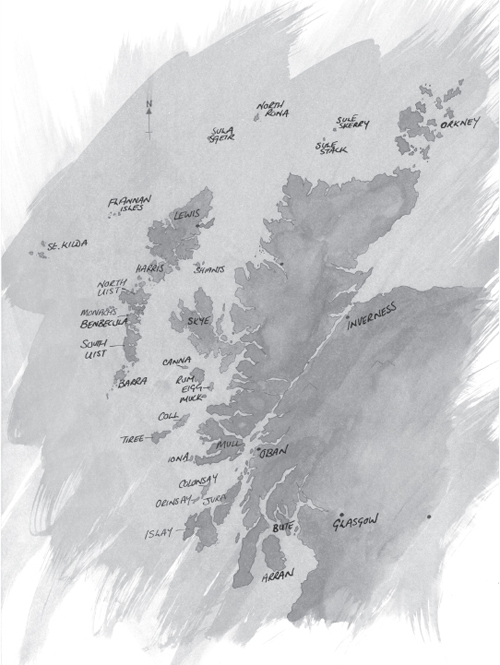

I was always driven to go out in small boats, sea-angling. Sailing came later. Usually we remained in sight of land, so you knew your position from recognising points. You built up a knowledge of the names of features. Out from the harbour, in small boats, the landmarks could alter. Headlands remained but a conspicuous building might change. You might have to remember that the grey roof was now red. An aerial could be felled. You were told the transits and you repeated them, when you were taken out to pull up haddock and whiting, ling or cod.

I was taught to locate a position over the seabed by observing points on land and holding them in line, or allowing a gap to open. The beacon on the lighthouse. Arnish light just open on Lamb Island. A gap at the Chicken. People talked about the hard ground and the roundabout and the more distant marks with the summit of Muirneag, north Lewis, in line with the visible geo at Dibidail. A few of my pals took a berth on a local trawler or creel-fishing boat. Some of them went on to master the sextant and work through their tickets to go from being a cadet to a mate in the Merchant Navy. I didnt join a local boat, didnt go to a tech college to study the practical arts of the fishing industry, didnt apply for a cadetship. Instead I studied education and literature. In no time at all I had been away to studies, in the sea city of Aberdeen, and back again. I had learned the basics of sailing by buying the most simple project craft, as a student. It was the smallest of Wharram catamarans, adapted from a timeless Polynesian design. I learned mainly by making mistakes. There was a fair element of luck in my survival.

After graduating with a qualification to teach English in Scottish secondary schools, I did shifts as an auxiliary coastguard in between writing short stories and poems. I also learned to take photographs, mostly by taking a very large number on process-paid Kodachrome that came back to me in yellow boxes of slides. First, the slivers of positive film were cased in card, then they were returned in plastic mounts. The words and the images were all elements of a need to keep a record of my own ways through water, or over land.

Much of my work took as its subject the topography, the built structures or the people of the islands where I was born and raised. Even the words or images composed in response to travels somehow related to home, by comparisons. Poems fell into groups and amounted to collections that I hoped were more than the sum of individual parts. Stories chimed off each other to explore themes. In the space of a few years, several books were published. An exhibition gathered together poems and photographic images. I gained a sense of being part of a wider community of writers, artists and publishers, extending way beyond native shores.