2022

PIERRE KROFT LEGACY PUBLISHERS

DISTRIBUTION CONTROLLED BY PIERRE KROFT BOOK DISTRIBUTOR

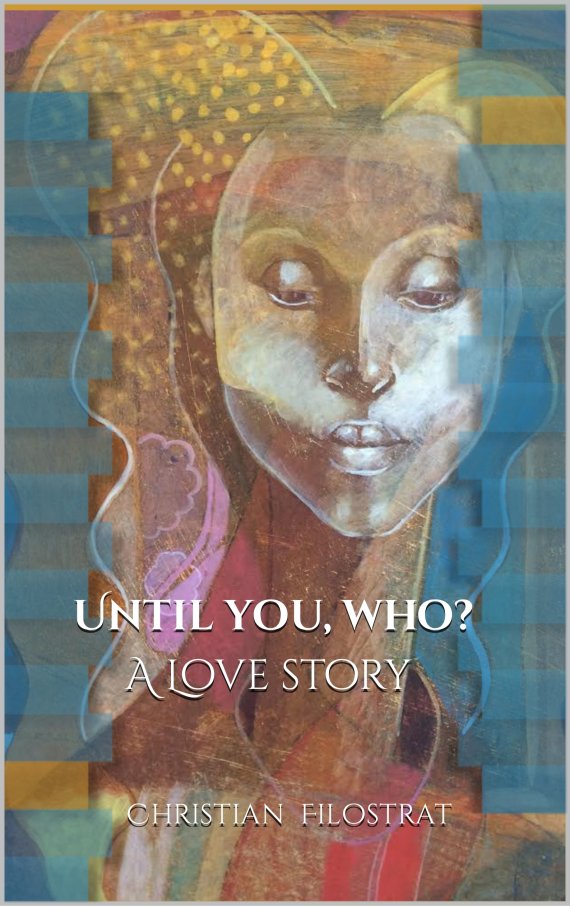

Until you, who?

A love story

by

Christian Filostrat

ALSO BY CHRISTIAN FILOSTRAT

Frantz Fanon in the U.S.A., followed by comments from Fanons wife

Negritude Agonistes

Containing China

PIERRE KROFT PRESTIGE LEGACY PUBLISHERS

4075 Jefferson Parkway

Lake Oswego, Oregon 97035

United States

Copyright 2022 Christian Filostrat

Publication date August 2022

All rights reserved.

Printed and bound in the United States of America

All rights reserved. No parts of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, except for short passages quoted by a literary critic, without the prior written permission of the publisher

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Filostrat, Christian

Until you, who? / Christian Filostrat

p. cm

1. Zaire DRC Belgian Congo Angola Leopold II Mobutu Sese Seko History. 2. Belgium Colonies History Blacks Race identity. 6. Cultural assimilation. I. Title

"Like all Europeans," Father Brabant declared, "you're having a first-day-in-Africa letdown." That will fade as soon as you become acclimated to the Congo. Your minds will adjust, not because the Congo has changed, but because you have embraced the opportunities to change the place. And you'll thank God for these opportunities, and you'll grow even more sympathetic to the Congo; you'll become champions of your captives. "You see," he continued, "things are out of place in Leopoldville's Bantu sector; the people you're passing through here belong in a forest or village somewhere out there, not in a city." You're witnessing the agony of a village giving birth to a city. Such origins are always agonizing. It was said to be agonizing in Europe during the Middle Ages. It's startling in Africa.

Filostrat, Christian

Until you, who? A love story

Until you, who?

A love story

W hen I fly, I talk to the people next to me. That helps me with my fear and advances the clock. In October 1999, on a flight from Kinshasa to Brussels, I spoke with a nun sitting next to me. Her Belgian nun life story in the Congo drew me in, especially because she was eager to share it with me. I paid close attention to what she said about the infection that was by then known as HIV/AIDS. She was sure she had dealt with it when she worked as a nurse in Wembo-Nyama in the 1950s. I also wrote down that she was heartbroken by the plight of the Congo, which she saw as doomed to an eternity in hells dead end. She could not have been more prescient in her assessment of the Congo. But most of what she told me was about Mria.

S ISTER IMMANUEL ENTERED the convent out of love for a classmate who aspired to be a nun. After 54 years of service as a nurse in the Congo, she yearns to share her love story.

The truth, her beloved, and the love story of her life deserve nothing less. It is therefore vital that her story be told accurately with no embellishment.

Suicide is a recurring issue in her life. An issue that like a jack-in-the-box keeps popping up again and again.

After learning that her mother had taken her own life on the day she took her vows, she began debating with herself, Is it possible to live, when there is nothing to live for? Her uncle and then her beloved followed suit. There were others.

She's left to witness the independence of the Congo on her own. Having arrived in 1945, she has a front row seat. In faithful detail, she recounts what the Congolese do and Belgiums maneuvers to maintain control over a colony synonymous with suffering. As to the question regarding suicide, she answers by describing how her own life ends.

S ince Jerome, my house servant, presented them to me at the ceremony of my investiture as head nurse of the Congo's Wembo-Nyama hospital on December 12, 1949, the pillows I'm propped up on have been a blessing. Dear Jerome spent over a year collecting down feathers from rare Cameroon Scrub-Warbler nests and making the pillows out of two lion skins purchased at the Leopoldville Central Market. He kept them in his room, waiting for the right occasion to give them to me. They are the world's two most comfortable pillows. When I returned to Tournai, my hometown in southwest Belgium that I had left fifty-four years before, I brought Jerome and the pillows with me. I've been grateful for them both more than any other gift.

Supported by Jeromes pillows, I give vent to my yearning to reach out to the world outside in my suite in Maison St Jean, Tournai's nursing home, with what I tell myself is a unique story a story thats neither narcissistic, nor prejudiced, nor a delirium, nor as people have told me to my face, the story of an old nun I prefer renunciant; nun was until recently a term of address for an old cloistered woman weaving her regrets and self-absorption into redemption for a wasted unnatural life. Of course, in the grand scheme of time, its not an exceptional story; but it is where it counts in the tale of two simple renunciants. When people read a significant story, they do not recognize it. So much the more, if it's a narrative about a nun celebrating herself. I wish people had the patience of my notebook, which can handle anything with a patient smile. Or, as young Anne Frank put it, " Papier heeft meer geduld dan mensen; " and it's true: paper has more patience than people.

In Maison St. Jean, I write about Mria and me for an hour in the morning, and if I have an evocative and heartfelt prayer without being interrupted by my friend the word before 3 p.m., I write for another hour and a half in the afternoon. I talk to myself and my notebook about what and how much I should say. Anxiously, I remind myself that I have a duty of confidentiality, which is a sworn pledge not to reveal anything that could harm my order. The tension between my anxiety and the urge to tell about my life is heightened as a result.

Fortunately, Kathryn Hulme's Nun's Story , a 1956 novel, delves into the daily life of a nun, from her first day as an aspirant to the day she takes her final vows and beyond. It follows the Belgian nun's journey from becoming a nun to leaving the convent and walking into a war-torn world. I've read many books, but this one is the most beautiful. Because of Nuns Story , Im less apprehensive to talk about my life as a nun. The journey that Ms. Hulme describes is so detailed that when I read the Nun's Story in one night, it reminded me of the kilometers of Priscilla's Catacombs, tunnels that run under Rome, and the Basilica of San Silvestro that I visited in 1964. In the Hulme story, even the nun's underwear is discussed. And, of course, its all about the Rules that everyone has to follow, which are laid out in their full glory and discussed over and over again. I keep Nuns Story by my bed and reread it constantly as if it were my own journal, knowing that it's easier to talk about someone else than about yourself. If you are an outsider or if you live your life via the experiences of other people, you run the risk of being obsessed with facts. When the need is sharp, an insider needs to be specific, cautious, and even deceptive, and this is especially true when a person they care deeply about is involved. What else could I possibly add to this? Surprisingly, talking about Mria makes talking about myself less difficult to deal with. Fortunately, Ms. Hulme's novel is rich in the nun's self-denial and the convent's Machiavellian strategy to deceive life, or "her life against nature," as Ms. Hulme puts it. That has given me the opening I needed to tell Mria's and my stories without getting bogged down in the details of a nun's convent life and betraying our vows. I figure that since Ms Hulme has already covered everything there is to know about a Belgian nun's daily life in obsessive detail and more beautifully than I could ever do, I can be perverse - not contrarian - about divulging the indulgences Mria and I didn't deny ourselves out of shame, arrogance, or delight, and don't forget the inescapable fact of old age. Then I can turn Ms. Hulme's Nun's Story on its head by telling the stories of two nuns who broke the Rules to be themselves. So, now that I don't have to worry about saying something I shouldn't, I focus on the sanctum of Mria and me instead of the sanctum of sisterhood. So, thanks to Ms Hulme's novel, ours can focus on fashioning a journey filled with personal accounts from an insider's experience, to bring knowing smiles from women or frowns from prelates, or both, from whoever takes an interest in our story. But I don't delude myself. No one will believe me, especially men whose posturing about women has nothing to do with women. Still, I worry that it will be forbidden to tell the story of two young nuns having blissful sex in the style of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas. But my desire to connect with the outside world is compelling, and I don't give up, even though I can't escape the fact that I'm old. I worry that my health will fail me, and I don't want to have to rely on the staff, who call me "La Folle de Tournai" instead of Sister Immanuel. I don't want to have to ask for their assistance. (They came up with the name after learning about the play La Folle de Chaillot by Jean Giraudoux.) So far, they say it behind my back because they're preoccupied with the inheritance they hope to receive from my estate. Next week, though, that might change. But I'm keeping an eye open. I'm not stupidly waiting to croak. My biggest fear is that I won't do right by my beloved or by the love story part of my history, or that I'll say too much and write a clunky hagiography of someone who isn't a saint. Or that I won't tell the love story of my history as it should be told

Next page