The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

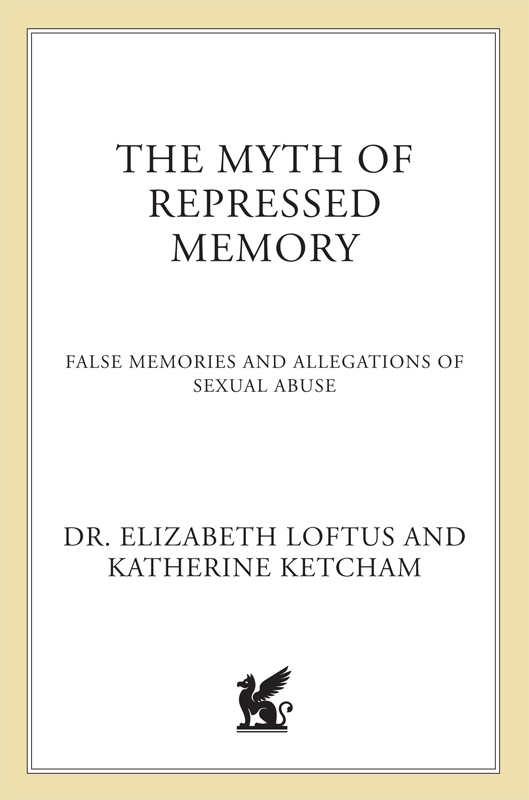

Dedicated to the principles of science, which demand that any claim to truth be accompanied by proof

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to express our deep gratitude to the many people who offered their help and support during the three years we worked on this book. We are especially grateful to:

the families and individuals who told us their stories. Many of the people we interviewed asked to remain anonymous in order to spare their families further pain; thus, while we cannot mention them by name, we honor their contribution;

Raymond and Shirley Souza, Lynn Price Gondolf, Laura Pasley, Melody Gavigan, Phil and Susan Hoxter, Chuck and June Noah, Jennifer and Pamela Freyd, and Paul Ingram who taught us so much about the anguish of both accuser and accused;

Steve Moen for legal insights and advice;

Richard Ofshe, whose wit, wisdom, and plain speaking frequently lifted our sagging spirits;

Lawrence Wright, author of Remembering Satan (Knopf, 1994); Harry N. MacLean, author of Once Upon a Time (HarperCollins, 1993); and Stephanie Salter (San Francisco Examiner columnist and co-author of the Examiner s April 49, 1993 series Buried Memories/Broken Families), for generously sharing their ideas and research;

Ellen Bass, Lucy Berliner, Karen Olio, Gerald Bausek, David Spiegel, George Ganaway, Paul McHugh, Joseph Barber, Gayle Gulick, Nelson Cardwell, Ricardo Weinstein, Marsha Linehan, and Margaret Hagen for illuminating discussions about psychotherapy;

William Calvin, who reviewed various sections dealing with the physiological mechanisms of memory;

the National Science Foundation and the National Institute of Mental Health, for supporting Elizabeth Loftuss research efforts in the area of the malleability of memory;

the student members of the Repressed Memory Research Group at the University of Washington;

Jane Dystel, our indefatigable and delightful literary agent;

Charles Spicer, our editor at St. Martins Press, who proves that the substantive editor is alive, well, and energetically active in New York. We are grateful for that, and for him;

Ilene Bernstein, Lonnie Rosenwald, and Diana Arnold, for their friendship and support;

Melinda Burgess, who helped frame the direction of this book and constantly affirmed its central purpose;

Tracee Simon, for careful readings of the manuscript and suggestions for improvement;

Sharon Kaufman-Osborn, Chris Anderson, and Delores Humphreys, for their insights into the therapeutic process;

Callie Walling, Jacquie Pickrell, and Michelle Nucci, for valuable research assistance;

Geoffrey Loftus, Maryanne Garry, and Steve Ceci, who were unfailingly generous with their time and compassion whenever the letters, calls, or e-mail took a hostile turn;

Robyn, Alison, and Benjamin Spencer, who continually bring home to their mother, Kathy Ketcham, the knowledge that family matters more than anything;

Patrick Spencer, who proves through his patience, sense of humor, and loving attentiveness that the near-perfect husband and father does indeed exist;

the family of Elizabeth Loftus (the Fishman, Breskin, and Loftus family members), who deserve enduring gratitude and affection for all they have taught her about the importance of protesting injustice. It was her family who first introduced her to the writings of Elie Wiesel. There may be times when we are powerless to prevent injustice, Wiesel wrote, but there must never be a time when we fail to protest.

AUTHORS NOTE

In our research for The Myth of Repressed Memory we conducted hundreds of interviews with accusers and accused, therapists, lawyers, psychologists, psychiatrists, sociologists, criminologists, and law enforcement personnel. We read thousands of pages of scholarly and popular books and articles on the subjects of memory, trauma, therapy, and recovery. The stories we tell in this book rely on the recollections and reconstructions of those involved in the separate dramas, as well as on our own personal memories of the events described. Certain scenes and dialogue have been dramatically re-created in order to convey important ideas or to simplify the story; some letters and other written materials have been paraphrased (in particular, Megan Patterson s letters in Chapter 10); and trial transcripts and testimony were edited in places to make the material more understandable and readable.

Although we have tried to correct obvious biases and base our accounts on the known and undisputed facts, these retrospective interpretations will undoubtedly contain inaccuracies. While we struggled throughout for balance and fairness, we may have misremembered or, through our own biases, misreported the facts. We apologize in advance for any distortions of memory that remain after all the editing and polishing stages involved in writing and publishing a book. We hope the reader will understand and forgive.

The names and identities of certain individuals were changed, at their request, to protect their privacy; in those cases, the name is italicized the first time it appears.

As a final note, we offer our respect and appreciation for the efforts of the many talented and devoted therapists who help victims of incest and sexual abuse cope with the aftermath and long-lasting memories of these traumas. We trust that they will understand that our purpose is not to attack therapy, but to expose its weaknesses and to suggest ways that it might better help those who enter its doors seeking help for their problems. We are not therapists, and any criticisms we offer come from the perspective of our research and experience in the field of memory.

We hope readers will remember that this is not a debate about the reality or the horror of sexual abuse, incest, and violence against children.

This is a debate about memory.

John Proctor: There might also be a dragon with five legs in my house, but no one has ever seen it.

Reverend Parris: We are here, Your Honor, precisely to discover what no one has ever seen.

Arthur Miller, The Crucible

SUCH STUFF AS DREAMS ARE MADE OF

What we are really, and the reality we live, is our psychic reality, which is nothing butget that demeaning nothing but the poetic imagination going on day and night. We really do live in dream time; we really are such stuff as dreams are made of.

James Hillman, Weve Had a Hundred Years of Psychotherapy and the Worlds Getting Worse

Shirley Ann Souza was a mothers dream. She was the sweetest, most darling, delightful, brilliant child, her mother remembers. In high school, Shirley Ann was on the softball team and captain of the basketball and volleyball teams. A member of the National Honor Society, she graduated nineteenth in her class.

After graduation, Shirley Ann worked in a mental health facility and began studying for a pharmacy degree. Then, when she was twenty-one years old, Shirley Ann was violently raped. In the months after the assault, her grades plummeted. She transferred to a school closer to home, and her parents bought her a car so that she could visit them on the weekends. Less than a year later, in the summer of 1988, Shirley Ann was again the victim of a sexual attack; in August 1989, her assailant was convicted of assault and battery and sentenced to eighteen months in prison.