Sarah E. England

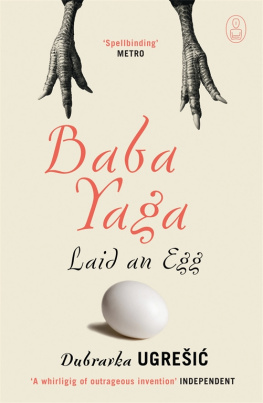

BABA LENKA

AN OCCULT HORROR NOVEL

Something drops from eyes long blind,

He completes his partial mind,

For an instant stands at ease,

Laughs aloud, his heart at peace

W.B. Yeats.

Eldersgate, YorkshireMay 1979

Nicky Dixon took the parcel from the postman, thanked him and tore it open. Inside was a bound manuscript. Bloody hell, it was from Eva! She hadnt seen her in how long over a year? Eva Hart had been her best and only friend from the age of eight to sixteen, but one year ago, about a month after Evas sixteenth birthday, shed vanished. Totally. No goodbye. No warning. No nothing.

Pulling out hundreds of dog-eared, scruffy handwritten pages, she frowned. It looked as though this had been written in the dark parts of it scrawled in pencil, others smudged and near illegible with a leaky Biro.

My dearest Nicky, you are the only person I can send this to

Within the first few minutes of reading, her heartbeat picked up. Some of this Eva had tried to tell her shortly after they first met. Shed recognised then that her friend was battling with the dark side. But the more she read, the more she understood. Goose bumps rose on her skin, and her eyes widened. Many hours passed until soon it was dark.

Forcing herself to take a break, she rubbed her aching neck. Dear God, poor Eva what a terrible burden. This was so much worse, so very much more frightening than anything she could ever have imagined.

It wasnt simply Eva who was in trouble, though. It was what Eva had brought with her.

Rabenwald, BavariaFebruary 1970

A raw wind rushed straight from the mountains that day, the kind that whipped skin to ice. Fresh from the snowcaps, it whistled down the slopes and howled through the trees.

The small procession of mourners trailing Baba Lenkas coffin paused momentarily on the hill to the cemetery, gasping in the fresh onslaught. Ice blew off pines in swirls of white dust. It stuck to eyelashes, peppered lungs and froze faces. There werent many of us immediate family, the priest, and six elderly mourners at the helm. The rest of the villagers had hung back and refused to come, their expressions dark and unreadable as they stood watching us leave. But the old folk were different, almost as if they were from a bygone age the women swathed in long, dark robes and headscarves, the men in trousers cut short at the knee and waistcoats fastened over full-sleeved shirts. Swarthy-skinned, their demeanour was quietly watchful. They did not speak much to those in the village, or indeed to us, but in hushed tones amongst themselves.

Less than an hour before, the two old women in the group had washed and prepared Baba Lenkas body for burial, after which the water used had been carried out to the farms well and tipped away. They stood out there in the frozen yard, heads bowed, muttering in a foreign tongue that carried on the wind. The men then joined them to form a circle, and with heads thrown back they began a strange kind of ceremony, calling and wailing into the wind.

Wed watched from the farmhouse kitchen window.

What are they doing? I asked my mother.

Silently she shook her head, narrowing her eyes at the screeching, cawing birds overhead.

We had arrived the day before. I was seven years old, cold, miserable and hungry. Baba Lenka had been my great-grandmother, but Id never met her. Nor did I understand why we had to come: spring was about to burgeon back home in England, snowdrops and crocus shivering on roadsides, sunlight chasing clouds across the school playing fields She was ninety-six, they said. Even my mother had never been to Rabenwald. It was freezing, the air biting, cobbles glistening with ice. And towering over the valley were mountains so huge they stood like giants with their heads in the clouds, the blue light of the snowy slopes ominous, eerie, deadly.

If only this were all over that we had never come here. Baba Lenkas farmhouse didnt even have running water. Wed arrived late yesterday afternoon to find the kitchen cupboards bare except for mouse droppings, and all the mirrors and windows had been covered with black cloths. It had the feel of a church crypt, and if it had ever been a welcoming home, it would be difficult to picture that. In the grim half-light, with the wind rattling the windows and whining down the chimney, my dad tried to get a fire going, and my mother chipped at packed ice outside to get water for the kettle. There was an all-pervading chill in that house, which once experienced could not be shaken, the kind that gripped the bones and iced the marrow. Mould spotted the wallpaper, damp coated the woodwork, and frost glazed the glass.

As evening plunged into the black of night, my mothers footsteps creaked up the old staircase to where we would have to sleep, the wind screaming like banshees around the eaves, candlelight flickering over the walls. I trailed behind her, shivering. But on reaching the landing, she caught her breath, and we both stopped to stare. Baba Lenkas bedroom door was ajar. We saw then what we didnt want to see the deathbed soiled and sagging where her body had lain decaying for weeks and weeks on end.

The room had been stripped of all possessions. Tidemarks left by her bodily fluids had stained the sheets dark yellow, and the sour stench of terminal disease cloyed the air. As we stood on the threshold, the sound of howling wolves echoed from the woods, and the noise of the wind intensified to violent and insistent. It seemed so very much louder up here, as if it was gaining in strength. Hypnotised, I couldnt look away, the Alpine coldness seeping under my skin

Suddenly, catching me totally off guard, I was in the old ladys mind lying there in the bed, dying in my own filth with a throat caked dry. Silvery light streaked through the curtains, and a murderous vixen screech rent the night air. The whole room was rumbling and juddering. The house seemed to shake on its very foundations, the floor tipping sideways A burst of crippling pain ripped through my chest, the heart muscle squeezing and twisting

I think I blacked out at that point, stumbling backwards, because the next thing I knew, my mother grabbed my arm and shut the door behind us.

Come on, Eva lets make the back bedroom nice and warm. Well bunk up together in there. Thank God its only for a couple of nights.

The vision had lasted for a second at most, but the effect lingered. My great-grandma had endured a terrible death.

Downstairs, her body lay in the parlour, where it had been wrapped in a coarse blanket and awaited preparation. It was our job as family, said my mother, to make sure all Baba Lenkas personal things were located and put into the casket, ready for burial. As such, she set me the task of checking drawers and cupboards for jewellery, photographs and trinkets. Nothing must be taken. Everything must go with her to the grave.

There was nothing left in the house, though. Every cupboard and drawer lay empty apart from a few old and very dirty books, which my mother kept.

Earlier, not long after wed arrived, while Dad was still getting the fire going, I had heard Mum shouting with someone at the door. It had turned out to be one of the old women whod come to prepare the body. My mothers German was halting, but she seemed to thank them, after which she came in to tell my dad what it had been about.

I think she was saying no one would tend to Lenka while she was ill. Those in the village say she was a Bluthexe and wouldnt come, so they contacted the old ones. She said theyve travelled a long way, and by the time they got here, the storm had blown over. Thats how they knew she was already dead. She doesnt seem to speak much German. I dont know what it is theyre speaking, but its like nothing Ive ever eard in my life. Anyway, I think thats the gist of it.