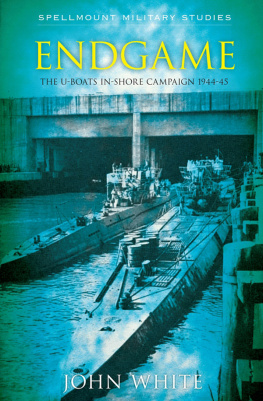

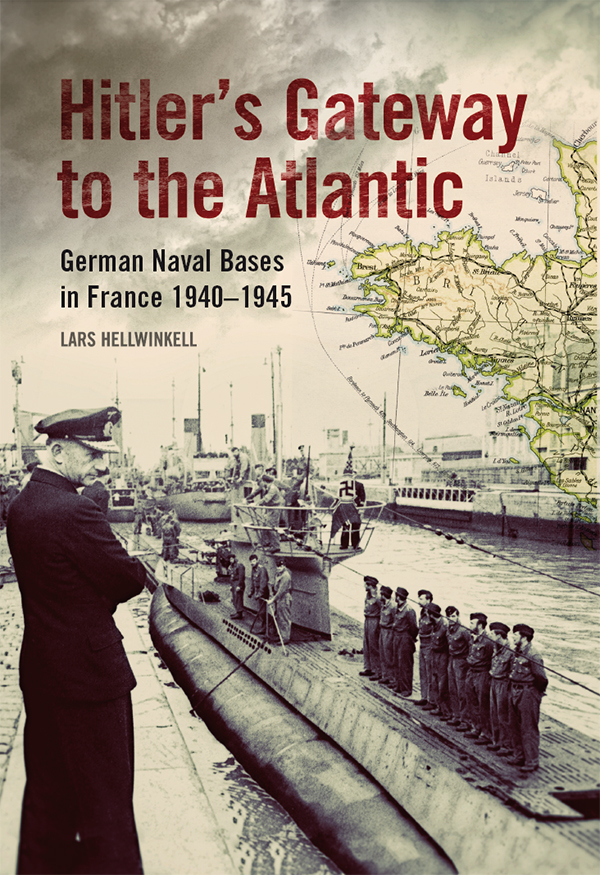

U588 commanded by Kptlt Viktor Vogel entering St-Nazaire in 1942. (Bundesarchiv, 101II-MW-6029-31A)

Copyright Christoph Links Verlag GmbH 2012

English translation Seaforth Publishing 2014

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by

Seaforth Publishing,

Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street,

Barnsley S70 2AS

First published in 2012 under the title Hitlers Tor zum Atlantik by Ch. Links Verlag

www.seaforthpublishing.com

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

ISBN 978 184832 199 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced

or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic

or mechanical, including photocopying, recording,

or any information storage and retrieval system, without

prior permission in writing of both the copyright

owner and the above publisher.

Typeset and designed by M.A.T.S., Leigh-on-Sea, Essex

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Contents

Introduction

The image that springs to mind when thinking about the French Atlantic and Biscay ports in the Second World War is one of German U-boats running into or departing from the huge U-boat bunkers built for their protection.

At the outbreak of war the German U-boat arm had fifty-seven submarines, of which only about half were suitable for operations in the Atlantic. As the war went on, Admiral Karl Dnitz, the Commander-in-Chief of the U-boat arm, transformed the U-boat into one of the most important weapons available to the Kriegsmarine in the naval war against Great Britain.

The German maritime armaments industry was redirected to step up U-boat production, and by the end of the war 1,110 boats had been turned out. Of these 757 were lost and with them 29,000 submariners, a casualty rate of almost 70 per cent. Although most of these men ultimately died for no purpose, particularly towards the end of the war, to this day the myth of a blood brotherhood surrounding the U-boat fleet persists.

In Germany, the autobiographical novel Das Boot, written by former war correspondent Lothar-Gnther Buchheim, and Wolfgang Petersens film based on the book, revived the myth, although the film gave rise to much controversy amongst U-boat veterans. The fascination with U-boats remains undiminished, as can be seen from the growing number of U-boat museums on the German coast, from the World War II boat at Laboe to submarines of the former post-war Bundesmarine, and the Soviet Cold War spy boat at Hamburg.

So what was it really like to serve aboard a U-boat? Looking at an exhibition of Buchheims photographs, what are particularly striking are the facial portraits of the crewmen. These faces reflect anxiety as depth charges explode, are etched with the fear that an Allied bomber might yet attack the boat before it reaches port, or are joyful at having completed a voyage safely once more.

The bases themselves remain in the background, rather as if they were merely stage sets. The memoirs of individual U-boatmen are concerned mainly with wartime voyages and life aboard; one learns little or nothing about the ports and how the crew lived in the period between putting in and sailing again. Against Buchheims well-known photographs of the bridge watch on the tower, swamped by monstrous seas crossing the bow, bearded men in the torpedo rooms, or indoor boxing in the U-boat bunker, the images of picturesque Breton stone houses and precipitous rocky cliffs seem out of place. Nor is much known about the French who had daily contact with U-boatmen for over four years.

Sources pose a problem for a sociohistorical investigation into everyday activities and life in the naval bases. More than sixty years after the end of the war, most of the participants, French and German, have passed on. Only a handful of them set down their experiences for posterity in writing, and in most cases these were former officers. The published experiences of simple sailors and yard workers are modest in scale and usually sparing in their references to the French. Thus the French rarely find mention in German memoirs, and in French literature, the Germans are generally discussed in their role as occupiers.

The official archives are of little help, because the major part of the Kriegsmarine documentation relating to the yards was destroyed when the central office of naval construction in Berlin was bombed. All military documentation, charts and photographs held in the bases along the Biscay coast were destroyed before the final surrender in May 1945. Thus all that the German Federal Archive BA/MA has to offer is the war diary for 1942 kept privately by the senior yard director of the main U-boat base at Lorient. Hardly any files survived from the no less important naval base of Brest. The Seekriegsleitung War Diary made available in facsimile by the official German archive makes only limited references to events at that port. Information specific to the region can be extracted from the almost complete archived war diaries of the commanding admirals and naval commanders in France, but on the other hand almost nothing by way of documentation exists in the archives from the subordinate service offices, such as the harbour commanders or naval commanders, the real points of intersection between the French and Germans. Thus the history of the French Atlantic bases during the German occupation relies on the few published memoirs of those involved.

In France, on the other hand, particularly when it comes to the two naval bases, Brest and Lorient, there is comprehensive material available in the French navy archives, amongst them files from the technical directorates of the two naval arsenals, as well as the relevant French Admiralty staffs in Vichy and Paris. For the mercantile ports, St-Nazaire, La Pallice and Bordeaux and the private shipyards, however, there are neither files nor academic investigations available: for example, into the role of the French shipbuilding industry under German occupation. French historians have favoured a culture of reminiscence, with, quite understandably, a leaning towards everyday life under the occupation and what the French Resistance did, rather than the activities of the occupying forces. The fact is that the naval bases with their purely industrial orientation were places of intensive co-operation between occupiers and occupied: their use by the occupying force was only possible with recourse to the French yards, suppliers and labour force.

Of the thousands of workers who worked directly or indirectly for the Germans during the occupation, nobody wanted to discuss this aspect of the war after the Liberation, above all those involved. And so the history of the French Atlantic ports enters the debate regarding the economic and political collaboration of Vichy France with the German Reich. The subject of this book is accordingly less about the details of U-boat bunker construction and the U-boat war, and much more about the general development of the German naval bases facing the Atlantic, from the first strategic considerations in 1925 to the occupation of the French coast in the summer of 1940, and the capitulation of the last Atlantic redoubt in May 1945. In addition, there is a sociohistorical consideration of life around the bases, with a glance at modern attitudes towards this history in the ports concerned.

The text which follows is a completely revised and expanded version of my 2006 dissertation on the German Kriegsmarine base at Brest, accepted by the Christian-Albrecht University, Kiel and the Universit de Bretagne Occidentale, Brest, which was published in 2010 by Dr Dieter Winkler. I am grateful to the Christoph Links publishing house for accepting this manuscript into their schedule, and to all colleagues, especially reader Stephan Lehrem, for their untiring patience and the expert advice and industry made during the production of this book.